D

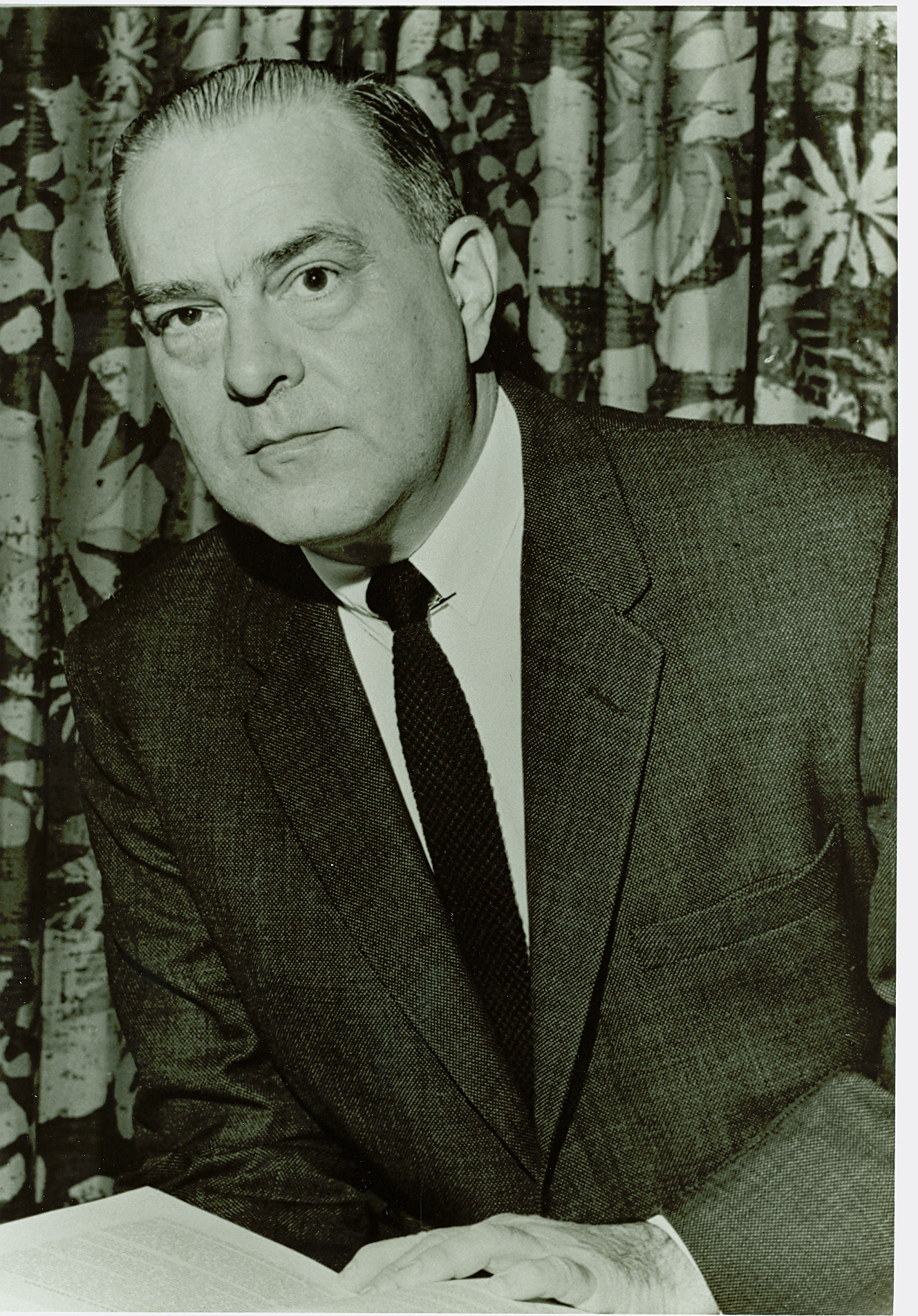

Darrah, Theodore (1914-1995)

Professor of Religion & Dean of Chapel

Born in Boston, Massachusetts on January 31, 1914, Theodore Darrah came from a family which emigrated from Scotland to Prince Edward Island, Canada, then to Quincy, Massachusetts, where Darrah spent his childhood years. The combination of his Scottish blood, New England upbringing and enrollment with a group called the Christian Endeavors brought about his love for religion, and by the age of fifteen, Darrah made up his mind to enter the ministry. [1] After completing Harvard College with a Bachelors of Science degree, Darrah returned to the College to receive another Bachelors in Sacred Theology. Directly after graduation, he journeyed to Europe, where he met his wife, Cornelia Sanders Scott of St. Paul, Minnesota, for the first time. Together, they moved to Connecticut, where Darrah became a minister in the Ellington Congregational Church in Connecticut. He remained at the Church until 1943 before relocating to Salisbury, Connecticut, where he preached at until 1947.

Born in Boston, Massachusetts on January 31, 1914, Theodore Darrah came from a family which emigrated from Scotland to Prince Edward Island, Canada, then to Quincy, Massachusetts, where Darrah spent his childhood years. The combination of his Scottish blood, New England upbringing and enrollment with a group called the Christian Endeavors brought about his love for religion, and by the age of fifteen, Darrah made up his mind to enter the ministry. [1] After completing Harvard College with a Bachelors of Science degree, Darrah returned to the College to receive another Bachelors in Sacred Theology. Directly after graduation, he journeyed to Europe, where he met his wife, Cornelia Sanders Scott of St. Paul, Minnesota, for the first time. Together, they moved to Connecticut, where Darrah became a minister in the Ellington Congregational Church in Connecticut. He remained at the Church until 1943 before relocating to Salisbury, Connecticut, where he preached at until 1947.

During that year, Dr. Holt called upon Darrah to join the Rollins College faculty. Darrah graciously accepted the invitation as the fourth dean of the Knowles Memorial Chapel and eventually earned the title of full professor of religion, taking delight in pointing out that his only previous teaching experience had been in instructing Sunday school. Almost immediately, he took liking to those on campus, where during his early years, “students played games and tricks on him, but he always took it in good fun.” [2] The years following, he became known around campus for his adeptness with the plunger and wrench, and then later, as the father of four children, two of which graduated from Rollins. Darrah remained at the College for twenty-five years, until his resignation from the position as Dean of Chapel in 1973 for a one-year sabbatical leave to study at the University of Edinburgh, Scotland. Although his main purpose consisted of bringing himself up to date with Biblical research, he also felt the need to experience life on the other side of the fence to improve his teaching as well as enjoy the lack of responsibilities. [3] Darrah returned to Rollins a year later, where he continued his teaching of philosophy and religion and worked as an assistant to Rollins President Jack Critchfield. After another six years of teaching, Darrah took up teaching the Old and New Testament part-time at the College. Darrah’s semi-retirement from the College gave him more time to devote to another of his interests: clocks. Over time, he had become fascinated with them, because they gave him, “an acute sense of time.” [4]

Time soon caught up with Darrah, and on March 12, 1995, Theodore Darrah passed away. The personality and character that Darrah exhibited to those around him have best been summed up with the words which were read to him at the 1973 Rollins Commencement when he was presented with the honorary degree of Doctor of Humanities. He will forever be remembered as, “the scourge of the administration, an implacable foe of red tape, the custodian of thousand and one faculty and student confidences, and always a jealous advocate of freedom of the pulpit, and worship.” [5]

Time soon caught up with Darrah, and on March 12, 1995, Theodore Darrah passed away. The personality and character that Darrah exhibited to those around him have best been summed up with the words which were read to him at the 1973 Rollins Commencement when he was presented with the honorary degree of Doctor of Humanities. He will forever be remembered as, “the scourge of the administration, an implacable foe of red tape, the custodian of thousand and one faculty and student confidences, and always a jealous advocate of freedom of the pulpit, and worship.” [5]

– Alia Alli

Dean, Nina Oliver (1901-1978)

Shakespeareana

Nina Oliver Dean, born on July 19, 1901, grew up in Columbus, Mississippi with her parents John and Laura (Sturtevant) Oliver. As a little girl, Dean, along with her brother and two sisters, received the Sunday afternoon uplifting treatment by having the Bible and Shakespeare read to them by their parents [6]. Inspired by her childhood readings, Dean attended Mississippi State College for Women and later Columbia University for her Masters, where she majored in English literature. While at Columbia, Dean studied under the illustrious Brander Mathews, a scholar who introduced her to the idea of combining the literary with the dramatic study of Shakespeare. Dean’s interest with Shakespeare cultivated even further with her attendance to the Claire Tree Major Dramatic School, where she took part in its Shakespearean series. Dean continued to study the great master at Harvard, where she worked towards her doctorate while simultaneously serving on the staff of the Atlantic Monthly, and The New York Times Magazine. After graduation, Dean taught for a brief period at Mississippi State College.

Nina Oliver Dean, born on July 19, 1901, grew up in Columbus, Mississippi with her parents John and Laura (Sturtevant) Oliver. As a little girl, Dean, along with her brother and two sisters, received the Sunday afternoon uplifting treatment by having the Bible and Shakespeare read to them by their parents [6]. Inspired by her childhood readings, Dean attended Mississippi State College for Women and later Columbia University for her Masters, where she majored in English literature. While at Columbia, Dean studied under the illustrious Brander Mathews, a scholar who introduced her to the idea of combining the literary with the dramatic study of Shakespeare. Dean’s interest with Shakespeare cultivated even further with her attendance to the Claire Tree Major Dramatic School, where she took part in its Shakespearean series. Dean continued to study the great master at Harvard, where she worked towards her doctorate while simultaneously serving on the staff of the Atlantic Monthly, and The New York Times Magazine. After graduation, Dean taught for a brief period at Mississippi State College.

Inspired by Hamilton Holt’s Conference Plan for Rollins College, Dean joined the faculty of Rollins in 1943. She immediately gained popularity for her attitude towards teaching. Those that enrolled in her class felt that she made the poetry of her Shakespeare course “a personal living experience” and the content of her Southern literature course, “an epitome of her own self.” [7] Others admired her dedication as faculty advisor for Libra, the women’s honorary leadership society which later merged with Omicron Delta Kappa. Hamilton Holt also noticed her commitment towards teaching and promoted Dean from assistant professor to associate professor in 1947. Dean continued to impress those around her, especially on the Annie Russell Theatre stage, where she played various roles, including Amanda, the mother in The Glass Menagerie. Despite her dedication, the financial situation at Roll ins necessitated the release Dean’s services to the College. In 1967, President McKean reappointed Dean to the Rollins faculty. Dean only  stayed for two years, a period in which colleague Wilber Dorsett recalled, “Dean was prone to accidents, and for a long time, she wore a metal body brace for an injury caused by an automobile accident. Her office was on the second floor, but she was loath to ask for favors and would not tolerate any suggestion that her office be moved to the first floor.” [8]

stayed for two years, a period in which colleague Wilber Dorsett recalled, “Dean was prone to accidents, and for a long time, she wore a metal body brace for an injury caused by an automobile accident. Her office was on the second floor, but she was loath to ask for favors and would not tolerate any suggestion that her office be moved to the first floor.” [8]

Because of Dean’s indomitable spirit and stubborn nature, Nina Oliver Dean’s life came to a sudden end on April 30, 1978. To honor the memory of such an outstanding woman, a Nina Dean Awards Fund, memorializing the associate professor of Rollins, was established at the College. The awards fund, set up by Mr. and Mrs. Martin Andersen and Howard Phillips with an initial contribution of $1000, enables the annual cash award to a Rollins English major who presents the best critical essay for senior independent study. [9]

-Alia Alli

Dommerich, Louis Ferdinand (1841-1912)

Maitland Settler and Rollins Trustee

Louis F. Dommerich was born on February 2, 1841 in Cassel Germany. His father was a college professor. In 1859, Dommerich came over to the United States where he worked for a s an apprentice in a German factory, Noell & Oelbermann, which served as a direct agent for a foreign manufacturing. He was employed there for ten years before becoming a partner in the renamed E. Oelbermann & Co. In 1889 the company was renamed once again to Oelbermann, Dommerich and Co. His company specialized in dry goods exchange and bank dealing in textile commerce, and became so successful that it had manufacturing companies all across the United States and Europe. [10]

Louis F. Dommerich was born on February 2, 1841 in Cassel Germany. His father was a college professor. In 1859, Dommerich came over to the United States where he worked for a s an apprentice in a German factory, Noell & Oelbermann, which served as a direct agent for a foreign manufacturing. He was employed there for ten years before becoming a partner in the renamed E. Oelbermann & Co. In 1889 the company was renamed once again to Oelbermann, Dommerich and Co. His company specialized in dry goods exchange and bank dealing in textile commerce, and became so successful that it had manufacturing companies all across the United States and Europe. [10]

In 1885 Dommerich visited Florida for the first time, and two years later he visited Winter Park and stayed in the Seminole Hotel. In 1991 Dommerich bought 400 Acres of land in Maitland Florida. His holdings included the orange groves on Lake Minnehaha. It was there that he built his first home in Maitland and called it “Hiawatha Grove.” His wife, Clara J. Dommerich established the Maitland Public Library in 1896 and Louis Dommerich was its major contributor. In 1907 he donated $3,000 in memory of his late wife. From 1897 to 1904, Dommerich served on the Rollins College Board of Trustees. [11] He and his wife founded the Florida Audubon society in 1900 and served as president from 1901 to 1911. In 1903 Dommerich donated $5,000 towards Rollins College’s first endowment. In 1907 Dommerich donated $500 to help secure Carnegie Library and in 1910 he donated $1,000 to help secure a science building. Back on the Board in 1909, he remained a trustee until his death.

Louis Ferdinand Dommerich died at the age of 72 on July 22, 1912. His son Alexander Louis Dommerich served on the Board of Trustees as his other son Otto Louis Dommerich helped Hamilton Holt finance the College in 1927. [12] By the time Louis Ferdinand Dommerich died, his company had become one of the most prominent commercial banking houses in the world. Hiawatha Grove stood until 1954 when it was torn down to make way for homes in the area.

– David Irvin

Dorsett, Wilbur (1912-1980)

English Professor

Born December 25, 1912, Wilbur Dorsett graduated from Spencer High School in Spencer, North Carolina at the age of eighteen. From there, Dorsett went on to attend the University of North Carolina (UNC), where he majored in English. While attending to his undergraduate studies, Dorsett worked on the technical staff for the Carolina Playmakers. He later received a Rockefeller Scholarship to pursue a Master of Arts degree at UNC, achieving receiving his degree in goal in 1936. After leaving UNC, Dorsett worked as a technical director for the summer theater program at the New England Repertory Company in Maplewood, New Jersey and as assistant manager for The Lost Colony at the Waterside Theatre in Roanoke, North Carolina. [13] After leaving these jobs, Dorsett began his teaching career at Wesleyan College and Conservatory in Macon, Georgia. There he taught dramatic arts and directed the theatre until the late 1930s, when he relocated to North Carolina to teach at the Woman’s College of the University of North Carolina. After a brief period with the Intuition, Dorsett affiliated himself with the University of Virginia and Michigan State University before joining the Rollins faculty in 1946.

While at Rollins, Dorsett used the knowledge he gained while studying at the Shakespeare Institute of the University of Birmingham in England to teach a Shakespeare class “that was one of the most popular courses in the curriculum.” [14] Dorsett also directed the Annie Russell Theatre program in his early years at Rollins, where he became most notable for his productions of Romeo and Juliet and Henry IV, Part I. During the later part of his career, Dorsett authored a historical drama on the history of the College in a song titled Song of Rollins, a ballad that spoke of, “the old dinky railroad line whose tracks [were] yet to run a long Lake Virginia.” [15] He also collaborated on a play with music about Shakespeare called Muse of Fire and wrote many articles about poetry, theatre, and history. Among these included his publications Shards: A Scatter of Sonnets (1977) and Lightening in the Mirror (1980). As a resident of Winter Park, Dorsett also made his mark on the City. He served on the Board of Directors with the English Speaking Union and maintained an active role with the Winter Park Historical Association, the Florida Theatre Conference, and the South Atlantic Modern Language Association. For his dedication to such organizations, the Rollins community gathered in 1979 to celebrate the promotion of Dorsett’s permanent ranking to Professor Emeritus.

While at Rollins, Dorsett used the knowledge he gained while studying at the Shakespeare Institute of the University of Birmingham in England to teach a Shakespeare class “that was one of the most popular courses in the curriculum.” [14] Dorsett also directed the Annie Russell Theatre program in his early years at Rollins, where he became most notable for his productions of Romeo and Juliet and Henry IV, Part I. During the later part of his career, Dorsett authored a historical drama on the history of the College in a song titled Song of Rollins, a ballad that spoke of, “the old dinky railroad line whose tracks [were] yet to run a long Lake Virginia.” [15] He also collaborated on a play with music about Shakespeare called Muse of Fire and wrote many articles about poetry, theatre, and history. Among these included his publications Shards: A Scatter of Sonnets (1977) and Lightening in the Mirror (1980). As a resident of Winter Park, Dorsett also made his mark on the City. He served on the Board of Directors with the English Speaking Union and maintained an active role with the Winter Park Historical Association, the Florida Theatre Conference, and the South Atlantic Modern Language Association. For his dedication to such organizations, the Rollins community gathered in 1979 to celebrate the promotion of Dorsett’s permanent ranking to Professor Emeritus.

On November 4, 1980, friends and family of Dorsett gathered once again, this time to honor the memory of Wilbur Dorsett. “Wilber, in a way summarized what Dr. Holt talked about golden personality,” explained Hugh McKean. “He thought the teacher was the most important subject. Wilber Dorsett summed up the kind of teacher every college was looking for. He was great.” [16]

– Alia Alli

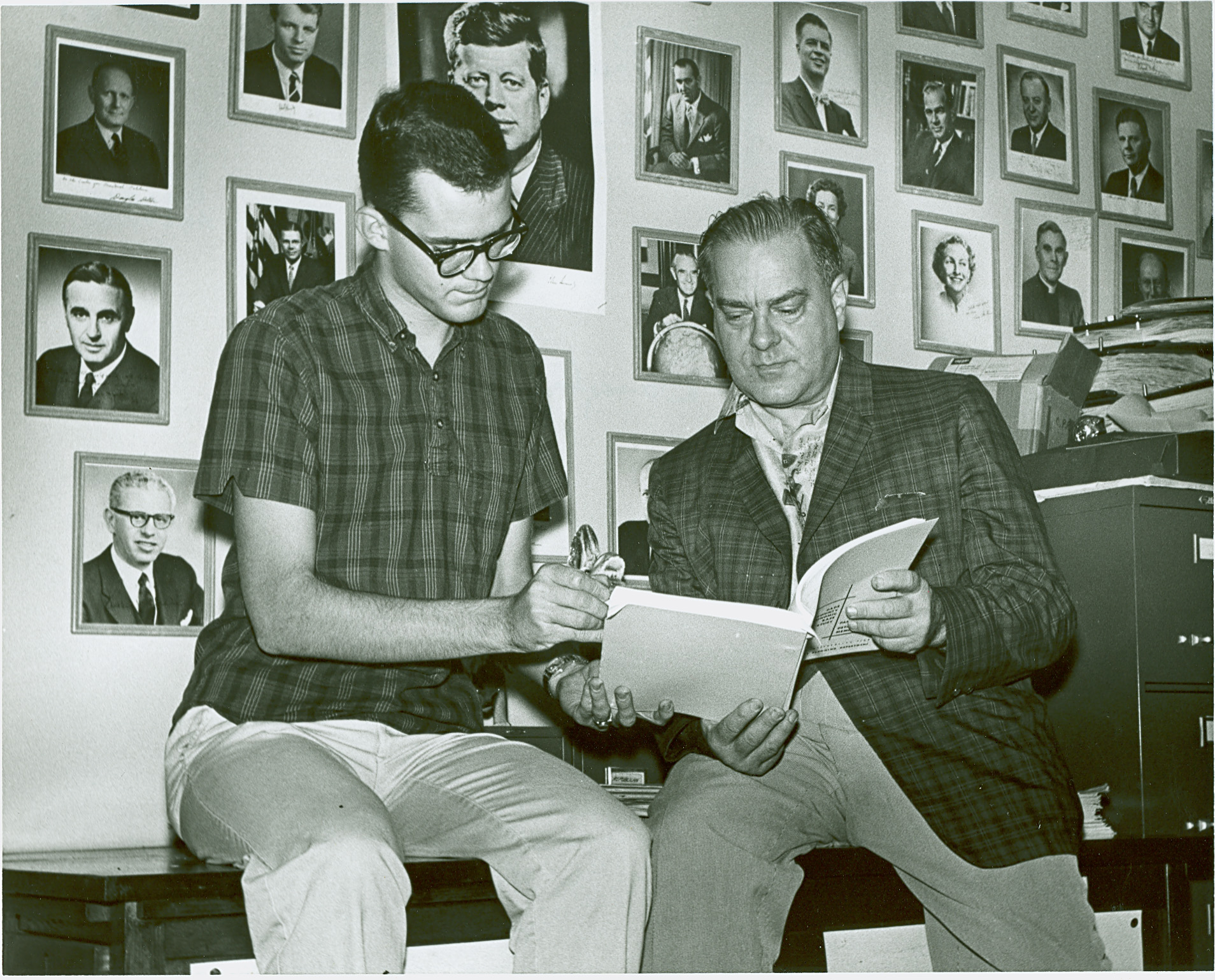

Douglass, Paul Fredrick (1904-1988)

“Political Scientist and Educational Leader”

Born on November 7, 1904, political scientist Paul Frederick Douglass grew up in Corinth, New York. He later moved, first to Connecticut, where he received his Artium Baccalaureatus degree from Wesleyan University, and then to Ohio, where he graduated with a Ph.D. in 1931 from the University of Cincinnati as a Taft fellow in government and public law. He then attended the University of Berlin for two years as a fellow in economics and jurisprudence and submitted to the Vermont Bar in the late 1930s.

Born on November 7, 1904, political scientist Paul Frederick Douglass grew up in Corinth, New York. He later moved, first to Connecticut, where he received his Artium Baccalaureatus degree from Wesleyan University, and then to Ohio, where he graduated with a Ph.D. in 1931 from the University of Cincinnati as a Taft fellow in government and public law. He then attended the University of Berlin for two years as a fellow in economics and jurisprudence and submitted to the Vermont Bar in the late 1930s.

Douglass worked his way through school, holding the positions as reporter and educational editor for the Cincinnati Post from 1926 to 1928. In 1933, the Methodist Church in Poultney, Vermont called Douglass to pastor their church. He simultaneously held this position, along with the office of Chairman of the House Committee on Education until 1943. Upon his resignation from both offices, Douglass was nominated to be the president of the American University by a special committee of the Board of Trustees. In his first month at the University, he took on the task of interviewing all the seniors, administering the graduate record examination, revitalizing the school’s chapel programs, and preaching to the students during Sunday services. Douglass continued to lead the Institution, even though the turbulent war years. He became increasingly active in World causes, helping to establish the United Nations and aid in the process of creating refugee relief programs and inter national organizations. In 1951, Douglass decided against reappointment to the presidency, and instead spent his time as advisor to the South Korean President Syngman Rhee for three years.

Douglass worked his way through school, holding the positions as reporter and educational editor for the Cincinnati Post from 1926 to 1928. In 1933, the Methodist Church in Poultney, Vermont called Douglass to pastor their church. He simultaneously held this position, along with the office of Chairman of the House Committee on Education until 1943. Upon his resignation from both offices, Douglass was nominated to be the president of the American University by a special committee of the Board of Trustees. In his first month at the University, he took on the task of interviewing all the seniors, administering the graduate record examination, revitalizing the school’s chapel programs, and preaching to the students during Sunday services. Douglass continued to lead the Institution, even though the turbulent war years. He became increasingly active in World causes, helping to establish the United Nations and aid in the process of creating refugee relief programs and inter national organizations. In 1951, Douglass decided against reappointment to the presidency, and instead spent his time as advisor to the South Korean President Syngman Rhee for three years.

Following his advisement to President Rhee, Douglass came to Rollins. There he became the Director of the Rollins’ College Center for Practical Politics. He remained at the College for fifteen years, during which time he took an active role in the study of campus subculture and academic achievement. During this time, he also authored several books, including Wesleys at Oxford (1953), Irving Babbitt and Paul Elmer More (1963), and Six Upon the World (1954). In 1971, Douglass chose to resign, with those close to him stating that the resignation came because he had become, “increasingly unhappy with the happenings of the College and did not go along with Rollins’ youthful president Dr. Jack Critchfield on certain subjects.” [17] Upon his retirement, he made plans to author several books. Instead, he moved to Washington, where he acted as General Counsel to the postmaster’s league in Washington. In 1973, Rollins College awarded Douglass with the Rollins Declaration of Honor for his distinguished career in government, journalism, and education. He passed away with such an honor just a few years later, on August 7, 1988.

Following his advisement to President Rhee, Douglass came to Rollins. There he became the Director of the Rollins’ College Center for Practical Politics. He remained at the College for fifteen years, during which time he took an active role in the study of campus subculture and academic achievement. During this time, he also authored several books, including Wesleys at Oxford (1953), Irving Babbitt and Paul Elmer More (1963), and Six Upon the World (1954). In 1971, Douglass chose to resign, with those close to him stating that the resignation came because he had become, “increasingly unhappy with the happenings of the College and did not go along with Rollins’ youthful president Dr. Jack Critchfield on certain subjects.” [17] Upon his retirement, he made plans to author several books. Instead, he moved to Washington, where he acted as General Counsel to the postmaster’s league in Washington. In 1973, Rollins College awarded Douglass with the Rollins Declaration of Honor for his distinguished career in government, journalism, and education. He passed away with such an honor just a few years later, on August 7, 1988.

– Alia Alli

Drinkwater, Geneva (1897-1997)

Internationalist and Professor of History

On October 15, 1897, Albert C. and Maud Sterett Drinkwater had their daughter in Charleston, Missouri. Geneva Drinkwater attended Charleston’s public schools for her preparatory education and, in 1915, received her associate’s degree from Stephens College in Colombia, Missouri. In 1917 Drinkwater received a bachelor of arts degree, in addition to a bachelor’s of science in education, from the University of Missouri. She then conducted some graduate studies as a Latin Scholar at Bryn Mawr College, Pennsylvania from 1917 to 1918, and served as a professor of history at Stephens College in Colombia, Missouri in 1918. After receiving her master of arts from the University of Chicago, Drinkwater studied at the Vatican School of Paleography and Diplomatique on the Carnegie Fellowship from 1929 until 1930. Drinkwater specialized in medieval history; during her time in Rome she translated documents from Latin into English at a Benedictine monastery. In 1931 she earned her doctoral degree from the University of Chicago, and then worked as a professor of history and dean of women at Carleton College in Northfield, Minnesota from 1931 to 1934. Drinkwater returned to Carleton to assist her mother after her father’s death in the 1940s. While in Carleton, she established the town’s first kindergarten and public library. She transferred to the Woman’s College at the University of North Carolina in Greensboro in 1935, serving as dean of women and history professor for one year. From 1935 to 1945 Drinkwater taught history at Vassar College in Poughkeepsie, New York, and at Scripps College in Claremont, California while on sabbatical leave from Vassar.

On October 15, 1897, Albert C. and Maud Sterett Drinkwater had their daughter in Charleston, Missouri. Geneva Drinkwater attended Charleston’s public schools for her preparatory education and, in 1915, received her associate’s degree from Stephens College in Colombia, Missouri. In 1917 Drinkwater received a bachelor of arts degree, in addition to a bachelor’s of science in education, from the University of Missouri. She then conducted some graduate studies as a Latin Scholar at Bryn Mawr College, Pennsylvania from 1917 to 1918, and served as a professor of history at Stephens College in Colombia, Missouri in 1918. After receiving her master of arts from the University of Chicago, Drinkwater studied at the Vatican School of Paleography and Diplomatique on the Carnegie Fellowship from 1929 until 1930. Drinkwater specialized in medieval history; during her time in Rome she translated documents from Latin into English at a Benedictine monastery. In 1931 she earned her doctoral degree from the University of Chicago, and then worked as a professor of history and dean of women at Carleton College in Northfield, Minnesota from 1931 to 1934. Drinkwater returned to Carleton to assist her mother after her father’s death in the 1940s. While in Carleton, she established the town’s first kindergarten and public library. She transferred to the Woman’s College at the University of North Carolina in Greensboro in 1935, serving as dean of women and history professor for one year. From 1935 to 1945 Drinkwater taught history at Vassar College in Poughkeepsie, New York, and at Scripps College in Claremont, California while on sabbatical leave from Vassar.

In 1952, Drinkwater came to Rollins College in Winter Park, Florida as an associate professor of history. She became a professor of history in 1959 until her retirement in 1963, when she received a Fulbright grant to serve as a visiting lecturer in history at the University of Madras in India. She returned to Winter Park a year later where she frequented the Winter Park Library and the First United Methodist Church. She actively served her community as the president of the local chapter of the American Association of the United Nations and as the chairman of the International Relations Committee for the American Association of University Women. Additionally, Drinkwater instructed adults in reading and writing through the Laubach Literacy program. She was a member of Libra, Pi Gamma Mu, Kappa Kappa Gamma, the Mortar Board, and an honorary member in the Rollins Key Society, which began in 1927 as an organization to increase interest in campus and scholastic activities while promoting the welfare of the College. She also joined the Southern Historical Association, American Historical Association and Medieval Academy of America, Florida Academy of Sciences, Board of Curators for Stephens College (in 1969 as an honorary life member), Association for Higher America, American Association of University Professors, American Association of University Women, League of Women Voters, Friends of Winter Park Public Library, Board of United Church Wo men, Council of Church Women, and the Methodist Church. Drinkwater published several works: Essays Presented to James Westfall Thompson (1938), and Medieval Library (1939). She died three months short of her one-hundredth birthday on July 21, 1997.

In 1952, Drinkwater came to Rollins College in Winter Park, Florida as an associate professor of history. She became a professor of history in 1959 until her retirement in 1963, when she received a Fulbright grant to serve as a visiting lecturer in history at the University of Madras in India. She returned to Winter Park a year later where she frequented the Winter Park Library and the First United Methodist Church. She actively served her community as the president of the local chapter of the American Association of the United Nations and as the chairman of the International Relations Committee for the American Association of University Women. Additionally, Drinkwater instructed adults in reading and writing through the Laubach Literacy program. She was a member of Libra, Pi Gamma Mu, Kappa Kappa Gamma, the Mortar Board, and an honorary member in the Rollins Key Society, which began in 1927 as an organization to increase interest in campus and scholastic activities while promoting the welfare of the College. She also joined the Southern Historical Association, American Historical Association and Medieval Academy of America, Florida Academy of Sciences, Board of Curators for Stephens College (in 1969 as an honorary life member), Association for Higher America, American Association of University Professors, American Association of University Women, League of Women Voters, Friends of Winter Park Public Library, Board of United Church Wo men, Council of Church Women, and the Methodist Church. Drinkwater published several works: Essays Presented to James Westfall Thompson (1938), and Medieval Library (1939). She died three months short of her one-hundredth birthday on July 21, 1997.

– Angelica Garcia

Dyer, Susan H. (1880-1922)

Music Faculty

Former graduate of the U.S. Naval Academy George Leland Dyer and Susan Heart Palmer Dyer gave birth to Susan “Daisy” Hart Palmer on December 20, 1880 in Annapolis, Maryland. She received instruction on these subjects in various settings-first in Annapolis and then in Washington D.C.-primarily because of her father’s military career. After her studies were completed, Dyer attended the Corcoran Art School in Maryland for two years, and then the Art Students League in New York City, graduating in 1896. According to Dyer’s diary, the next two years of her life consisted of traveling to Europe where her father was stationed. There, she gained insight into the nature of lifestyles and customs of the places she visited during the late Victorian period. [18] After leaving Europe, Palmer enrolled in the Peabody Conservatory of Music in Baltimore, Maryland, where she studied violin with J.C. Van Hulsteyn and harmony with Otis B. Boise, until her graduation in 1904. By the age of twenty-five, Dyer relocated to Guam, where the government appointed her “special laborer” for $2.50 gold a day until regular teachers arrived. [19] In her spare time, Dyer occupied herself with writing poetry and composing music. In 1910, The Anchorage published several of Dyer’s poems, including, “A Song,” and “Magnolia.”

Former graduate of the U.S. Naval Academy George Leland Dyer and Susan Heart Palmer Dyer gave birth to Susan “Daisy” Hart Palmer on December 20, 1880 in Annapolis, Maryland. She received instruction on these subjects in various settings-first in Annapolis and then in Washington D.C.-primarily because of her father’s military career. After her studies were completed, Dyer attended the Corcoran Art School in Maryland for two years, and then the Art Students League in New York City, graduating in 1896. According to Dyer’s diary, the next two years of her life consisted of traveling to Europe where her father was stationed. There, she gained insight into the nature of lifestyles and customs of the places she visited during the late Victorian period. [18] After leaving Europe, Palmer enrolled in the Peabody Conservatory of Music in Baltimore, Maryland, where she studied violin with J.C. Van Hulsteyn and harmony with Otis B. Boise, until her graduation in 1904. By the age of twenty-five, Dyer relocated to Guam, where the government appointed her “special laborer” for $2.50 gold a day until regular teachers arrived. [19] In her spare time, Dyer occupied herself with writing poetry and composing music. In 1910, The Anchorage published several of Dyer’s poems, including, “A Song,” and “Magnolia.”

Dyer’s love for music brought her to Rollins in 1909 as instructor of violin. She remained at the College for two years, until she resigned in 1911 to enroll in Yale Music School. After completing her Bachelor of Music degree and receiving the Steinert Prize for the overture she wrote in 1914 titled, “Florida Night Song,” Dyer returned to Rollins. There, she became instructor in violin, harmony, theory, and musical history as well as the director of Rollins College Conservatory of Music  and head of the Department of Theory. After contributing to the College for thirteen years, Dyer announced her final resignation in March 1922 . September of that year, Dyer became directress of Greenwich House Music School Settlement. She also continued her services to the Florida Federation Women’s Club as President until her death on October 21, 1922.

and head of the Department of Theory. After contributing to the College for thirteen years, Dyer announced her final resignation in March 1922 . September of that year, Dyer became directress of Greenwich House Music School Settlement. She also continued her services to the Florida Federation Women’s Club as President until her death on October 21, 1922.

To commemorate the services that Dyer dedicated to Rollins, the College erected the Dyer Memorial Music Building as, “a memorial not only to an inspired teacher, Susan Dyer, but to her well-remembered mother and father, beloved residents of Winter Park.” [20]

-Alia Alli

For more information on Susan Dyer, please see: https://lib.rollins.edu/olin/oldsite/archives/golden/Dyernew.htm

- Kelly Pflug, “An Interview With Dr. Theodore S. Darrah, Former Dean of Knowles Memorial Chapel at Rollins College, Winter Park,” May 27,1987, p 2. ↵

- Sue Hong, “Rollins Students to Miss Cigar-Chomping Chaplain,” Sentinel Star, May 19, 1973. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Joanne Park, “The Dean,” The Rollins Alumni Record, 1985. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ruth Smith, “Shakespeare’s Fan,” Department of Archives and Special Collections, Box 45E, Olin Library, Rollins College, Winter Park, Florida. ↵

- Wilber Dorsett, “Personal Memories of Nina Dean,” Alumni Record, 1978. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Charlie Wadsworth, “ Fund Memorializes Outstanding Woman,” Sentinel Star, May 22, 1978. ↵

- Trustee file: Louis Ferdinand Dommerich. 10 B, Rollins College Archives. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- “The Lost Colony,” Sandspur, October 8, 1963. ↵

- “Wilber Dorsett, Rollins Scholar,” Sentinel Star, November 6, 1980. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ed Hayes. “Wilber Dorsett: A Friend of Writers,” Star Sentinel, November 16, 1980. ↵

- "Dr. Douglas Resigns From Rollins Staff," Cupboard News, May 10, 1971. ↵

- Beth H. Carter, “Susan ‘Daisy’ Hart Dyer,” Box 45E, Olin Library, Rollins College, Winter Park, Florida. ↵

- Ibid., 3. ↵

- Ibid., 5. ↵