G

Galloway, Josey K. (1911-1978)

Telephone Pioneer and Rollins Contributor

Josey K. Galloway was born in Beaumont, Texas in 1911. In 1912 he moved to Winter Park with his family. He attended Winter Park public schools and graduated in 1929. He then joined his father, Carl H. Galloway Sr., at the Winter Park Telephone Company. After graduated from the University of North Carolina with a degree in electrical engineering. Galloway returned to Winter Park and resumed working with the Winter Park Telephone Company. Galloway joined the navy just before America’s involvement in World War II. He continued his naval career for seven years and earned the rank of commander before returning to Winter Park months after the war in 1946. Galloway became president of Winter Park Telephone Company in 1959. He served as president until 1967 when he was elected as chairman of the board. In 1973 he served as president of the United States Independent Telephone Association and remained on as a member of its board for several years. He also served on the board of the Florida Telephone Association. Galloway retired from an active role in the Winter Park Telephone Co. in the spring of 1978. He continued to serve as executive committee chairman until his death later that year. [1]

Josey K. Galloway was born in Beaumont, Texas in 1911. In 1912 he moved to Winter Park with his family. He attended Winter Park public schools and graduated in 1929. He then joined his father, Carl H. Galloway Sr., at the Winter Park Telephone Company. After graduated from the University of North Carolina with a degree in electrical engineering. Galloway returned to Winter Park and resumed working with the Winter Park Telephone Company. Galloway joined the navy just before America’s involvement in World War II. He continued his naval career for seven years and earned the rank of commander before returning to Winter Park months after the war in 1946. Galloway became president of Winter Park Telephone Company in 1959. He served as president until 1967 when he was elected as chairman of the board. In 1973 he served as president of the United States Independent Telephone Association and remained on as a member of its board for several years. He also served on the board of the Florida Telephone Association. Galloway retired from an active role in the Winter Park Telephone Co. in the spring of 1978. He continued to serve as executive committee chairman until his death later that year. [1]

Galloway served the Winter Park community as a member of many of the city’s charitable organizations such as the Winter Park Memorial Hospital Association, the Rollins College Board of Trustees, the Independent Telephone Pioneers of America, the Retired Officers Association and vice president of the Florida Chamber of Commerce. [2] The Florida Legislature passed resolution recognizing Galloway’s exceptional service in 1963. He received the similar honor from the governor two years later. In 1975, the United States Independent Telephone Association honored Galloway with its highest honor, the Distinguished Service Award for both industrial and community service. [3] He received an honorary Doctorate of Science and Business Administration from Rollins College on May 27, 1977. The Galloway Room in Mills Memorial Hall was given by his wife, Sarah B. Galloway, in her husband’s memory.

Galloway served the Winter Park community as a member of many of the city’s charitable organizations such as the Winter Park Memorial Hospital Association, the Rollins College Board of Trustees, the Independent Telephone Pioneers of America, the Retired Officers Association and vice president of the Florida Chamber of Commerce. [2] The Florida Legislature passed resolution recognizing Galloway’s exceptional service in 1963. He received the similar honor from the governor two years later. In 1975, the United States Independent Telephone Association honored Galloway with its highest honor, the Distinguished Service Award for both industrial and community service. [3] He received an honorary Doctorate of Science and Business Administration from Rollins College on May 27, 1977. The Galloway Room in Mills Memorial Hall was given by his wife, Sarah B. Galloway, in her husband’s memory.

– David Irvin

Gleason, Catherine Crozier (1914-2003)

Professor of Music and Accomplished Organist

Catharine Crozier, born on July 18, 1914 to Walter Stuart, a retired Presbyterian minister, and Alice Condit Crozier, originated in Hobart, Oklahoma. As a young girl, Crozier enjoyed playing the organ, piano, and violin. Owing to her proficiency in music, she could publicly perform by age six. She received her preparatory education at Central High in Pueblo, Colorado from 1927 until 1931. A year later Crozier began her undergraduate studies at the University of Rochester, at the Eastman School of Music. She graduated in 1936 with a Bachelor of Music degree and a Performer’s Certificate. Later that year, Crozier began graduate studies at the Eastman School, which awarded her a Masters of Music and an Artist’s Diploma in 1941. On April 9, 1942, Crozier married Harold Gleason, a teacher under whom she had studied music. From 1936 to 1956 Gleason served as an instructor, working her first two years as a fellowship teacher. She gave lessons in the organ, harpsichord, and church service playing. Additionally, in the summers of 1953 and 1955, she joined the faculty of the Andover Organ Institute. Gleason participated in a variety of honorary and professional organizations, such as Mu Phi Epsilon, Pi Kappa Lamda, the American Guild of Organists, National Music Teachers, and the Rochester chapter of the United Nations. Politically, Gleason identified as a Republican. Her other achievements included the publication of a portion of her thesis, “The Principles of Keyboard Technique in Il Transilvano by Girolamo Diruta,” which appeared in the Mu Phi Epsilon’s The Triangle and the Andover Institute Quarterly.

Catharine Crozier, born on July 18, 1914 to Walter Stuart, a retired Presbyterian minister, and Alice Condit Crozier, originated in Hobart, Oklahoma. As a young girl, Crozier enjoyed playing the organ, piano, and violin. Owing to her proficiency in music, she could publicly perform by age six. She received her preparatory education at Central High in Pueblo, Colorado from 1927 until 1931. A year later Crozier began her undergraduate studies at the University of Rochester, at the Eastman School of Music. She graduated in 1936 with a Bachelor of Music degree and a Performer’s Certificate. Later that year, Crozier began graduate studies at the Eastman School, which awarded her a Masters of Music and an Artist’s Diploma in 1941. On April 9, 1942, Crozier married Harold Gleason, a teacher under whom she had studied music. From 1936 to 1956 Gleason served as an instructor, working her first two years as a fellowship teacher. She gave lessons in the organ, harpsichord, and church service playing. Additionally, in the summers of 1953 and 1955, she joined the faculty of the Andover Organ Institute. Gleason participated in a variety of honorary and professional organizations, such as Mu Phi Epsilon, Pi Kappa Lamda, the American Guild of Organists, National Music Teachers, and the Rochester chapter of the United Nations. Politically, Gleason identified as a Republican. Her other achievements included the publication of a portion of her thesis, “The Principles of Keyboard Technique in Il Transilvano by Girolamo Diruta,” which appeared in the Mu Phi Epsilon’s The Triangle and the Andover Institute Quarterly.

In 1955, Gleason came to Rollins College in Winter Park, Florida as an assistant professor of organ. She expressed admiration for a liberal arts education and considered the “Rollins Plan” of instruction, based upon small groups studying together with guidance from a professor, as one of the chief benefits of the College. She also sympathized with the ideals of a Christian, non-sectarian institution. From 1956 Gleason also served as the organist of Knowles Memorial Chapel on the Rollins Campus. She later became an associate professor of organ, until her retirement from the school in 1969. Recognized throughout campus for her skill, Gleason devoted approximately five hours per day to practicing the organ and rehearsing for concerts. Touring with her husband (who also worked at Rollins as a music consultant), she performed in numerous major cities in the United States and European cultural centers, which suited her because she enjoyed traveling. In 1965 Gleason received an invitation to give a concert with the New York Philharmonic for the World’s Fair Festival, one of many bookings that testified to her international prestige. Throughout her illustrious career, her concerts received constant glowing reviews, such as this press release from Copenhagen: “What fascinated us above all was her ability to phrase as sensitively and delicately as one could expect only from the lips of a woodwind player or the bow of a stringed instrument….” [4] Gleason passed away on September 19, 2003 at the age of eighty-nine.

In 1955, Gleason came to Rollins College in Winter Park, Florida as an assistant professor of organ. She expressed admiration for a liberal arts education and considered the “Rollins Plan” of instruction, based upon small groups studying together with guidance from a professor, as one of the chief benefits of the College. She also sympathized with the ideals of a Christian, non-sectarian institution. From 1956 Gleason also served as the organist of Knowles Memorial Chapel on the Rollins Campus. She later became an associate professor of organ, until her retirement from the school in 1969. Recognized throughout campus for her skill, Gleason devoted approximately five hours per day to practicing the organ and rehearsing for concerts. Touring with her husband (who also worked at Rollins as a music consultant), she performed in numerous major cities in the United States and European cultural centers, which suited her because she enjoyed traveling. In 1965 Gleason received an invitation to give a concert with the New York Philharmonic for the World’s Fair Festival, one of many bookings that testified to her international prestige. Throughout her illustrious career, her concerts received constant glowing reviews, such as this press release from Copenhagen: “What fascinated us above all was her ability to phrase as sensitively and delicately as one could expect only from the lips of a woodwind player or the bow of a stringed instrument….” [4] Gleason passed away on September 19, 2003 at the age of eighty-nine.

– Angelica Garcia

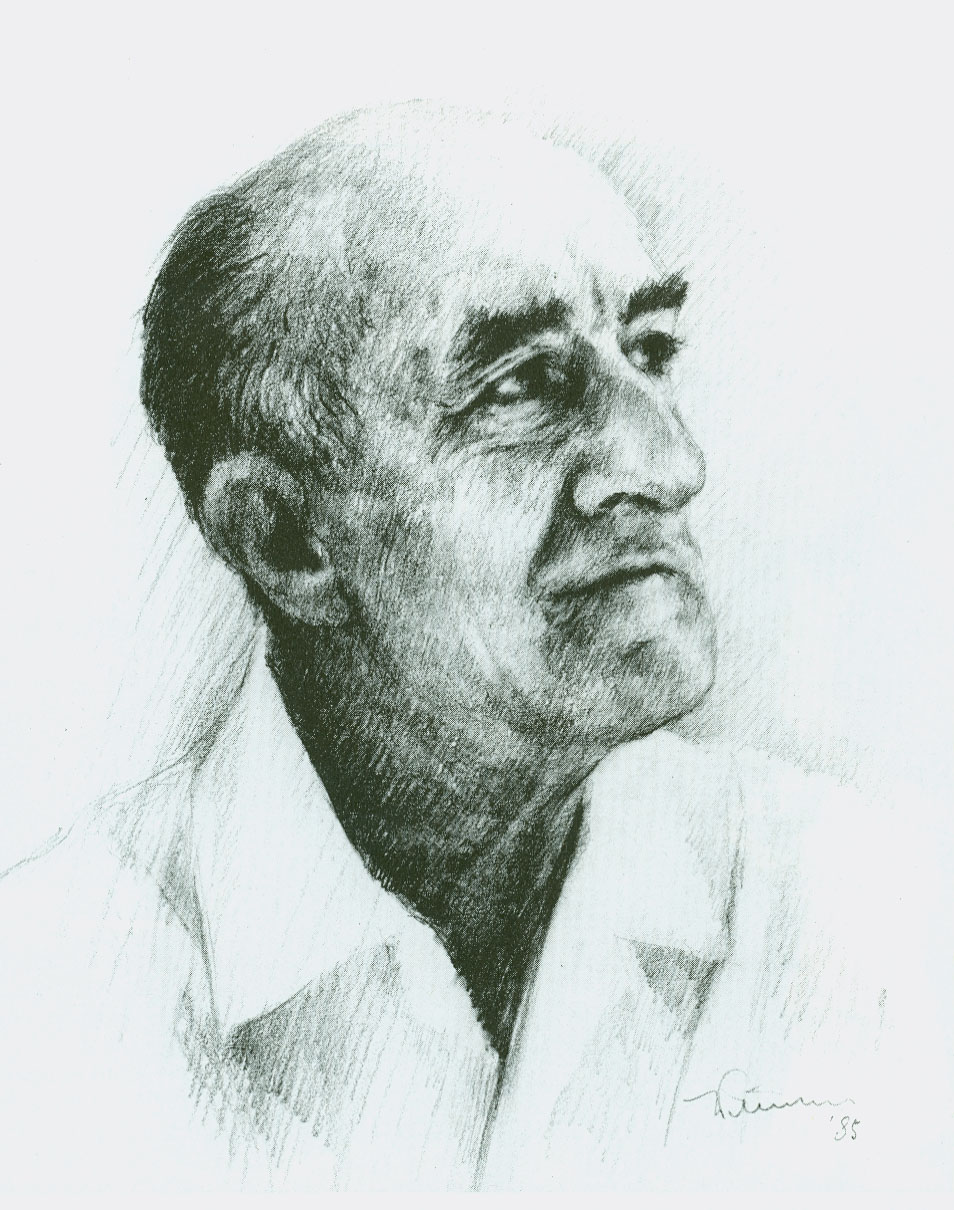

Granberry, Edwin (1897-1988)

English Professor & Noted Novelist

Born in Meridian, Mississippi on April, 18, 1897, Edwin Phillips Granberry lived in the Oklahoma Territory before moving to Florida at the age of ten. There, he attended the University of Florida from 1916 to 1918 until his studies were interrupted by his service with the U.S. Marines during World War I. Upon Granberry’s return in 1920, he enrolled at the University of Columbia, where he earned his Artium Baccalaureatus in Romance Languages. In 1920 to 1922, he became an assistant professor at Miami University (Ohio). Soon after, he attended George Pierce Baker’s famous “47 Workshop,” where his three-act comedy, “Hitch Your Wagon to a Star” was produced in 1924. [5]

Born in Meridian, Mississippi on April, 18, 1897, Edwin Phillips Granberry lived in the Oklahoma Territory before moving to Florida at the age of ten. There, he attended the University of Florida from 1916 to 1918 until his studies were interrupted by his service with the U.S. Marines during World War I. Upon Granberry’s return in 1920, he enrolled at the University of Columbia, where he earned his Artium Baccalaureatus in Romance Languages. In 1920 to 1922, he became an assistant professor at Miami University (Ohio). Soon after, he attended George Pierce Baker’s famous “47 Workshop,” where his three-act comedy, “Hitch Your Wagon to a Star” was produced in 1924. [5]

Soon after, from 1925 to 1930, while working as a private school language teacher, Granberry published three novels. The Ancient Hunger (1927), the first of his three books, told a story of romantic attraction and tragedy in an Oklahoma setting. Granberry’s remaining fictions explored the characters of Florida “scrub” pine country. [6] In his work, Strangers and Lovers (1928), Granberry introduced the Florida “Cracker,” and the rendering of innocence and doomed love that anchored in the backwoods of their daily lives. [7] Granberry’s most renowned story, however, came in 1933, when he authored A Trip to Czardis, a novel that presented a mother taking her two unwitting sons to visit their father for the last time. In 1934, A Trip to Czardis immediately received recognition from critics. It was awarded the O. Henry Memorial Prize and appeared more than forty times in magazine anthologies, and on radio and T.V. broadcasts. [8] Granberry soon began to work as a freelance book review and critic, having reviewed several pieces.

Most notable came in a glowing and unprecedented 1,200-word piece out of the novel Gone With the Wind in the New York Evening Sun on June 30, 1936. Margaret Mitchell, the author of the book, was so impressed by Granberry’s review, which compared her book to Tolstoy’s War and Peace, that it sparked a lifetime friendship between the two and convinced Mitchell to agree to accept $50,000 in movie rights for her book pending contract negotiations with producer David O. Selznick.

Most notable came in a glowing and unprecedented 1,200-word piece out of the novel Gone With the Wind in the New York Evening Sun on June 30, 1936. Margaret Mitchell, the author of the book, was so impressed by Granberry’s review, which compared her book to Tolstoy’s War and Peace, that it sparked a lifetime friendship between the two and convinced Mitchell to agree to accept $50,000 in movie rights for her book pending contract negotiations with producer David O. Selznick.

After reading Granberry’s work, Rollins College President, Hamilton Holt, also became mesmerized by Granberry and immediately appointed him to the Rollins faculty as assistant professor of English. Granberry accepted, and became so absorbed in fishing and surf-casting that he did not produce any literary work until after he received an honorary degree from Rollins in 1945. [9] In 1950, he finally wrote a three-play act titled The Falcon, which made its debut on the Annie Russell Theatre stage at Roll ins College during Founders’ Week, February 1950. Granberry continued to serve as Irving Bacheller Chair of Creative Writing until his retirement in 1971. After his departure with the College, he continued, with the help of artist Roy Crane, to co-write the nationally syndicated comic strip, Buzz Sawyer. Granberry died on December 5, 1988, at the age of 91, leaving behind three sons.

– Alia Alli

Greene, Raymond W. (1888-1979)

Rollins Graduate, Trustee & Civic Leader

Raymond W. Greene was born on May 22, 1888 in Oak Lawn, Rhode Island. In 1904, after graduating elementary school, he worked as an apprentice in steel textile engraving while taking courses on physical education at the YMCA. In 1913, he enrolled in Rollins College as a special student, allowing him to attend the undergraduate program as a post college age student while working as the physical training director. In 1915, Greene became the athletic director and continued to instruct physical training. Greene served as an officer of the YMCA in 1916 and in 1917, joined the army and fought in the First World War. He was put in charge of Athletics at the Charleston Navy Yard for the duration of the war. While there he had to monitor the physical development of over seven thousand sailors. He returned to Rollins College in 1919 and resumed his role as athletic director for the College. The next year he became secretary to the president of Rollins College. In 1921 Green attracted thousands to the Winter Park area by organizing interscholastic baseball and aquatic championships. [10] He continued his duty to the school by organizing and fundraising over 512,000 dollars for the endowment in only six weeks, greatly exceeding the goal amount of 127,000. In late 1921 Greene was elected to the National Olympic Committee in Paris. He became activities director at Rollins College and eventually graduated with an A.B. Degree in 1923.

Raymond W. Greene was born on May 22, 1888 in Oak Lawn, Rhode Island. In 1904, after graduating elementary school, he worked as an apprentice in steel textile engraving while taking courses on physical education at the YMCA. In 1913, he enrolled in Rollins College as a special student, allowing him to attend the undergraduate program as a post college age student while working as the physical training director. In 1915, Greene became the athletic director and continued to instruct physical training. Greene served as an officer of the YMCA in 1916 and in 1917, joined the army and fought in the First World War. He was put in charge of Athletics at the Charleston Navy Yard for the duration of the war. While there he had to monitor the physical development of over seven thousand sailors. He returned to Rollins College in 1919 and resumed his role as athletic director for the College. The next year he became secretary to the president of Rollins College. In 1921 Green attracted thousands to the Winter Park area by organizing interscholastic baseball and aquatic championships. [10] He continued his duty to the school by organizing and fundraising over 512,000 dollars for the endowment in only six weeks, greatly exceeding the goal amount of 127,000. In late 1921 Greene was elected to the National Olympic Committee in Paris. He became activities director at Rollins College and eventually graduated with an A.B. Degree in 1923.

In 1924 Greene drove Dr. Hamilton Holt around Winter Park. During this ride Greene explained all the problems of Rollins College. As a response to Greene’s questions Holt said “A college with that many problems certainly offers a challenge to anyone who would take the presidency.” Greene, while he was president of the alumni association, along with Irving Bacheller wrote to Hamilton Holt to convince him to come to Rollins College. Holt expressed interest in both letters and eventually became Rollins’ eighth president. [11]

In 1924 Greene drove Dr. Hamilton Holt around Winter Park. During this ride Greene explained all the problems of Rollins College. As a response to Greene’s questions Holt said “A college with that many problems certainly offers a challenge to anyone who would take the presidency.” Greene, while he was president of the alumni association, along with Irving Bacheller wrote to Hamilton Holt to convince him to come to Rollins College. Holt expressed interest in both letters and eventually became Rollins’ eighth president. [11]

After graduation, Greene began business in real estate. In 1925 he opened his own real estate office in the Hamilton Hotel. That same year he helped establish the Winter Park Board of Realtors and served as its president. He married Wilhelmina Freeman in 1926 and moved to Sebring, Florida in 1928, and along with Rex Beach established the Florida Parks Association Inc., which established Highlands Hammock, the first State Park in Florida. Greene moved back to Winter Park in 1934 and resumed his real estate business. In 1937 he served on the Winter Park City Commission and organized the Orange County Park and Recreation Association to purchase the Aloma Golf Course, where the city later decided to build the Winter Park Memorial Hospital. [12]

After graduation, Greene began business in real estate. In 1925 he opened his own real estate office in the Hamilton Hotel. That same year he helped establish the Winter Park Board of Realtors and served as its president. He married Wilhelmina Freeman in 1926 and moved to Sebring, Florida in 1928, and along with Rex Beach established the Florida Parks Association Inc., which established Highlands Hammock, the first State Park in Florida. Greene moved back to Winter Park in 1934 and resumed his real estate business. In 1937 he served on the Winter Park City Commission and organized the Orange County Park and Recreation Association to purchase the Aloma Golf Course, where the city later decided to build the Winter Park Memorial Hospital. [12]

In 1949 while serving as a trustee for the College, Rollins awarded him with the Rollins Decoration of Honor. [13] Greene filled in as mayor to finish Oliver Eaton’s term in 1952 and was reelected to another three year term in 1954. On April 1, 1961, he received the Hamilton Holt Medal for his services to Rollins College. In 1967 Rollins established the Raymond W. Greene Chair of Health and Physical education. Greene died on February 18, 1979 at the age of 90.

– David Irvin

Greene, Wilhelmina “Billie” (1906–1991)

Rollins Graduate, Lecturer & Botanical Artist

Wilhelmina “Billie” Greene was born Wilhelmina Freeman in Cincinnati, Ohio on January 27, 1906. Known as “Billie” to her friends and family, she spent winter months in Palm Beach, Florida throughout her childhood. She moved to Winter Park, Florida from Palm Beach in the 1920s. As a young woman she attended Goucher College in Maryland, Oberlin College in Ohio and graduated from Rollins College in 1927. She was a member of the Kappa Kappa Gamma Sorority.

Wilhelmina “Billie” Greene was born Wilhelmina Freeman in Cincinnati, Ohio on January 27, 1906. Known as “Billie” to her friends and family, she spent winter months in Palm Beach, Florida throughout her childhood. She moved to Winter Park, Florida from Palm Beach in the 1920s. As a young woman she attended Goucher College in Maryland, Oberlin College in Ohio and graduated from Rollins College in 1927. She was a member of the Kappa Kappa Gamma Sorority.

She married Raymond Greene, then Rollins College’s Athletic Director, in 1926. She had three children and worked as a homemaker. She showed great interest in the public education programs and youth development projects in the community. She taught and championed nature and art study in public schools. She even designed a Junior Garden Club program specifically for younger students. In the 1940s she served on the Winter Park School Board. She also loved to discuss philosophy and joined the Oxford Group, a local philosophy club. [14]

Billie Greene was most famous for her work as a botanical artist. She was nationally recognized for her drawings and paintings of flowers from all over the world. Green wrote two books on flora and in 1953 the University of North Carolina Press published her first book, Flowers of the South: Native and Exotic. This book served as an illustrated guide to the flowers of the American South. [15] The very same year she set out on a tour to sketch and draw the flora of the world. The result of the trip, her second book Tropical Flowers The World Over was never published. Greene nonetheless, loved spending her time traveling and lecturing about Botany all over the world.

In 1975 Billie Greene received the Rollins College Alumni Service Award. By the time of her death, Billie Green had donated over $30,000 to Rollins College. In 1980 the Winter Park Garden Club awarded Greene with a lifetime membership. Green died on September 18, 1991 after over 75 years of service to the Winter Park community.

– David Irvin

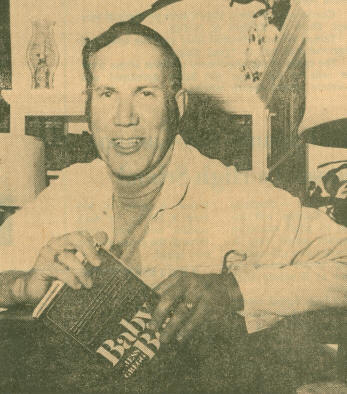

Gregg, Jess (1919-2009)

American Playwright and Author

Article as originally featured in Rollins Alumni Record, Vol. 67:2 (Summer 1989), 14-17.

Article as originally featured in Rollins Alumni Record, Vol. 67:2 (Summer 1989), 14-17.

When author and award-winning playwright Jess Gregg was 21 and a senior at Rollins College, his first short story, The Grand Finale, was published in Esquire. Certainly the plot had the boldness of youth: an apparently multi-gratified composer had five mistresses. The trouble began when he realized he was dying and concluded that his mistresses were coming around so often he couldn’t get his work done. In the imaginative denouement, the young Gregg had the composer pretend to die five times, in turn, in the arms of each of his mistresses.

While at Rollins, Gregg was also editor of the R Book, a normally bland rule book for freshmen. To the editor, the samples of previous issues he studied seemed as much alike as freshman caps. He made a decision to use a different approach. He not only rewrote every page, he also decided to spice things up with his own versions of what he regarded as “funny rather than sexy” drawings of those fat nude ladies in the “cutesy style of the 1880s.” He says today that college officials “were not amused.”

While these examples may adequately reflect the boldness and industry of the undergraduate imagination, they do not adequately anticipate a successfully sustained literary career that was to span at least five decades, a career that has not been without inner and outer conflict between two all-compelling callings: one to the novel, the other to the theatre.

His skills and accomplishments as a playwright have sometimes associated Gregg with such luminaries of the theater as Joshua Logan, Elia Kazan, Hal Prince, and the longtime Gregg family friend, the late Gower Champion, as well as with well-known actors and actresses. Playwriting, especially during the revisions-during-production phase, often involves travel and can be a social and learning experience for the playwright, if he so chooses. The writing of novels,  however, is essentially a loner’s calling. Virtually no group decisions are involved in the writing of first drafts of novels. Although he writes and speaks quite often of this at times frustrating and perhaps-at-times sublime rivalry, there is little doubt, when decision time is at hand, as to which of these muses he more readily responds. Any writer, year in and year out, must constantly decide what to undertake next- an often difficult determination. “What I work on next,” producer Stephen Spielberg once said, “is the most important decision I ever make.” The facts are that Jess Gregg’s long string of high-quality work includes twice as many plays as novels, even though he is presently finishing the first draft of a 400-page novel that, so far, has taken nearly four years to write.

however, is essentially a loner’s calling. Virtually no group decisions are involved in the writing of first drafts of novels. Although he writes and speaks quite often of this at times frustrating and perhaps-at-times sublime rivalry, there is little doubt, when decision time is at hand, as to which of these muses he more readily responds. Any writer, year in and year out, must constantly decide what to undertake next- an often difficult determination. “What I work on next,” producer Stephen Spielberg once said, “is the most important decision I ever make.” The facts are that Jess Gregg’s long string of high-quality work includes twice as many plays as novels, even though he is presently finishing the first draft of a 400-page novel that, so far, has taken nearly four years to write.

Which a gain brings back that rival muse, playwriting. A part of those nearly fifty months of fleshing out the novel was spent revising two plays. One, The Underground Kite, which opened in Central Florida in February of this year, underwent revisions — some after Gregg talked with actors about their conception of their parts. Another play, the musical comedy Cowboy, written with composer Richard Riddle, toured 11 western states in ’87 and ’88.

“I no longer know,” he said recently, “whether theatre is a blessing or a curse in my life. But saying no to it never crosses my mind.”

The late Dr. Edwin Granberry, Professor Emeritus of Creative Writing at Rollins, was both an author and a playwright. During the years, he and his former student read and criticized each other’s drafts and scripts. Gregg calls Granberry’s influence “simply enormous.” He even dedicated his issue of the R Book to his mentor: “From most, advice is small change. From him, it is a legacy.”

“Perhaps a little wide-eyed,” Gregg says of his dedication today, “but I still feel that way.” Appropriately, Gregg was at his typewriter last December when Howard Bailey, former director of the Annie Russell Theatre, phoned with news of Granberry’s death.

“I was,” Gregg wrote on a 1988 Christmas card, “full of gratitude that I knew him and learned from him and kept up with him all these years. I came from California to Rollins because of him. When I was a teenager in Beverly Hills High School and my father realized I was serious about writing, he made a thorough investigation of writer’s workshops and teachers. All roads led to Granberry.”

Gregg’s next stop after Rollins was a year at Yale Drama School. “Then,” he says, “I sat down at the typewriter.” He wrote first, not a play, but two novels. The first, The Other Elizabeth, was published in 1952. It attracted immediate attention, appearing initially in the Ladies Home Journal, but, he says, “so cut down as to be creepy, if not embarrassing.” The book sold well, was widely published in Europe, remained in print for years- in one language or another- and is still going the rounds on TV. Novelist Kay Boyle wrote that she had discovered the book while in prison for civil disobedience. Actress Bette Davis phoned one day to tell the author how much she liked it. “It was made for me!” she said.

Gregg’s next stop after Rollins was a year at Yale Drama School. “Then,” he says, “I sat down at the typewriter.” He wrote first, not a play, but two novels. The first, The Other Elizabeth, was published in 1952. It attracted immediate attention, appearing initially in the Ladies Home Journal, but, he says, “so cut down as to be creepy, if not embarrassing.” The book sold well, was widely published in Europe, remained in print for years- in one language or another- and is still going the rounds on TV. Novelist Kay Boyle wrote that she had discovered the book while in prison for civil disobedience. Actress Bette Davis phoned one day to tell the author how much she liked it. “It was made for me!” she said.

One reason Gregg and his father had decided on Rollins as the best place to begin was Granberry’s reputation as a perceptive, as well as lyrical, regional novelist. “In a sense,” Gregg says, “The Other Elizabeth was a regional novel, although today it might be called a Gothic. My second book, The Glory Circuit, which dealt with itinerant evangelists in Florida, was my first truly regional novel, a form which has always interested me.”

When this writer first came under the spell of its deft dialogue and consistent “real people,” The Glory Circuit seemed to possess much more valid regional perceptions on this subject than I had found elsewhere, even in Sinclair Lewis’s powerful Elmer Gantry.

Unfortunately, this novel came out during a newspaper strike. “It sold poorly,” says the author, “but Marilyn Monroe did want to play the white trash waif, Millie Marie. That put some rainbow into the experience.”

Jess Gregg’s first play, A Swim in The Sea, was brought out by Hal Prince, producer of Cabaret, West Side Story, and Phantom of the Opera. It was, as they say, a great way to start. It played Philadelphia and other cities-even, eventually, the Annie Russell Theatre at Rollins. But, like hundreds of other American plays, it never came to New York.

His second play, however, made England-in a conspicuous way. That was The Sea Shell, produced in 1960 by Stephen Mitchell and starring Sean Connery and that grand old actress and friend of George Bernard Shaw, Dame Sybil Thorndyke.

But how to sustain the art and skills needed for the long pull he had aligned himself for? For an actor, that sometimes means understudying an accomplished star. For Gregg, it meant assisting accomplished directors and producers. As early as the mid-fifties, his apprenticeship with three of the New York theatre’s best-known directors and producers began. Joshua Logan, who masterminded such hits as South Pacific and Mr. Roberts, hired him as his assistant on Fanny. He also worked as an assistant to Elia Kazan on Tennessee Williams’ Cat On A Hot Tin Roof. Choreographer and director Gower Champion used him in four shows, including Hello Dolly and I Do, I Do. Champion was , he says, his most important lifetime influence. They had grown up together in Los Angeles, their two families had been close for over a century-and Jess watched Gower grow into a major figure in the Broadway theatre. “He came to hire me because he was surrounded by people who only agreed with him, and he needed someone he could trust to argue with him when his ideas weren’t first-rate. Sometimes it got pretty sticky. We’d start talking about the show about a month before rehearsal, but my real work was during the out-of-town try-out where the show usually takes shape. Sometimes I didn’t know if I would emerge with a job, much less a friend.”

The friendship apparently survived, however, for Gower named his first son after Gregg. Champion’s early death was a great blow to Jess.

In 1964, Gregg’s play, Show From The Rooftops, was produced off-Broadway. Later, three one-act plays with an all-male cast, The Men’s Room, also appeared off-Broadway; of these, The Organ Recital at the New Grand won the John Gassner Award. In the ’70s, Gregg did the Broadway adaptation of an old Jerome Kern musical, Very Good Eddie, which played 90 performances at the Booth Theater.

Meanwhile, he did not forget the regional novel, or the investigative research required to dig it out and properly phrase it. A Florida ramshackle fish camp run by a man who hired ex-convicts provided the spark. “From talking to ex-cons,” he says, “I became interested in the problems of the convict’s upside-down existence in prison: living among enemies, the food, the humor, all of it. And the eventual problem of going out into the free world a gain. Finally I wrote the Florida Department of Corrections asking to be allowed into the penitentiaries for study. I told them I was not interested in sensational matter; my research would be simply to report. Somehow, they dared to let me, and I was given carte blanche to come and go in the Florida penal colonies. I even served at one of the road camps as a guard-without-gun.”

The experience mined enough human lode and authentic patterns of regional speech to fill, so far, a novel, a play, and a one-actor. Baby Boy, the novel, came first-in 1973. Its look behind the locks had an unsentimental sensitivity about it reminiscent of John Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men. Baby Boy was selected as Book-of-the-Month Club alternate. It was optioned by Hollywood, and Gregg went west to his old childhood home to write the screenplay for director Robert Mulligan (To Kill A Mockingbird).

Several other screenwriters were assigned to it. The story, as usual, got further and further away from the book. Eventually, it was optioned by Twentieth Century Fox, and later by Oliver Stone. “Now,” he says, “somebody else has it, and I’m afraid Baby Boy will be an old man by the time it’s done.”

In Florida prisons, an “underground kite” is a message slipped out of jail. Several years ago, Gregg’s most recently produced play, The Underground Kite, won a contest sponsored by Florida’s Theatre-in-the-Works, and in 1987, was presented for five performances as a ” staged reading”- first step towards production. Both Jess’s sister, Jenelle, and her husband, Howard Bailey, participated. Jenelle read the part of Lorraine, a tourist, and Howard, who had directed Jess in plays at Rollins long before, read “Gator,” the Florida cracker who ran the fish camp on the Huwatchee River.

Last February, Theatre-in-the-Works sponsored “The Premiere of a New American Play” at Valencia Community College’s Black Box Theatre for a week’s run. Gregg was there as a playwright-in-residence, a role he says is “usually a frustrating experience since everyone has to pretend the playwright doesn’t exist, and that the play was brought to the theatre by the stork.”

“But this time,” he adds, “I was allowed to work very closely with the director, Ed Dilks, and even encouraged to discuss the play with the actors. As a result, it was the kind of collaborative effort the theatre is supposed to be. The cuts suggested themselves painlessly, and a week after the curtain came down, I had the revisions ready for the script’s next step-whatever that may be.”

As the playwright knows best, chance plays the role of a giant in the American theatre. Jess never promotes or sends anything out on his own. According to Jenelle, he doesn’t even read, much less save, reviews. The way he divides things, the game of “Huwatchee The Kite?” is best played by his New York agent.

His musical play, Cowboy, roughly based on the life of Charles M. Russell, the cowboy artist, was first tried out at Connecticut’s prestigious Goodspeed Opera House in the mid-’70s. It has since had a number of productions regionally. Two years ago, it opened at the University of Montana’s sparkling new theatre, and a year later, the State of Montana, in celebrating its Centennial, presented the show in a tour of the far and middle western states.

It was also given a three-week New York showcase; but when the concrete canyons of that city will be ready for a full production of the play is anyone’s guess. This is a question for the rest of us, not a seasoned veteran like Jess Gregg . “Regional writing,” he says matter of factly, “hasn’t attracted much support from the commercial theatre, but it has gradually found audiences away from New York.”

At this writing, Jess Gregg is busy at his typewriter with what Jenelle admires as “his tunnel vision about writing. I’ve seen him take an entire day, or longer, in trying to get a sentence exactly right. Between his two work places, New York and Winter Park, he’s totally absorbed in his work.” His current absorption is a novel, four years and four hundred pages along. In the waggish spirit of his undergraduate days, he gives the same working title to any play or novel in progress: No Bed Of Her Own. The real titles come later. He’s been around long enough to have earned some traditions. Another is that he exerts no effort studying or following trends. And he doesn’t talk about-or “talk away,” as Hemingway once put it- any work in progress.

However, New York novelist Don Matheson, author of Stray Cat and the forthcoming Ninth Life, provides one insight: “I think of him as a writer who has a rare degree of commitment to quality. He avoids cheap tricks. He writes very slowly. He spends all day, every day, around his work. He is very good at turning a phrase. More importantly, he has the strength to put his phrases in the right setting.

“In his current novel,” he adds, “he’s coming closer and closer to what’s most important about what he knows best. He has a wealth of information about the movie industry in Hollywood, the theatre, offstage- all of it. His new book strikes me as one of the best things he’s ever written. It’s his world.”

For the rest of us, the new novel is something to look forward to: as a book, yes; as a play, maybe; as a movie, who knows? Jess Gregg has trained himself to do it-almost in his head-all three ways.

– Bill Shelton ’48

Grover, Edwin O. (1870-1965)

Professor of Books and Citizen of the Community

Edwin Osgood Grover was born in Mantorville, Minnesota on June 4, 1870. His father, Wesley Grover, was a congregational missionary to the Northwest Territory at that time. When Edwin was a few years old, his family returned to New England and his childhood was spent on the coast of Maine and in the mountains of New Hampshire. His love of nature was developed while roaming the woods and working in the fields, and this affection remained throughout his life. In 1890 he graduated from St. Johnsbury Academy in Vermont, and then worked his way through Dartmouth College where he graduated in 1894. It was there that he developed his literary interests, reporting for the Boston Globe during summer months and editing the Dartmouth Literary Magazine in the last two years of his college life.

Edwin Osgood Grover was born in Mantorville, Minnesota on June 4, 1870. His father, Wesley Grover, was a congregational missionary to the Northwest Territory at that time. When Edwin was a few years old, his family returned to New England and his childhood was spent on the coast of Maine and in the mountains of New Hampshire. His love of nature was developed while roaming the woods and working in the fields, and this affection remained throughout his life. In 1890 he graduated from St. Johnsbury Academy in Vermont, and then worked his way through Dartmouth College where he graduated in 1894. It was there that he developed his literary interests, reporting for the Boston Globe during summer months and editing the Dartmouth Literary Magazine in the last two years of his college life.

Shortly after graduation, Grover went to Harvard for graduate study. But he soon abandoned that plan and decided to see the world with only $300 in his pocket. For seven months he traveled through the old continents from the Shetland Islands to Algeria. The cost of his round trip by steerage was $19.60, and of his entire voyage $345. Returning to America in 1895, he worked for several years for the Ginn & Co. as a textbook representative in the Midwest. In 1900 he married Mertie Graham, a childhood friend and a graduate of Mount Holyoke College. Shortly after, he was promoted assistant editor of Ginn’s Boston office. In 1901 he become the chief editor of Rand McNally in Chicago, and in 1906 he formed his own publishing company where he was the editor and vice president for several years. In 1912 he sold his interest and became president of the Prang Company, whose crayons and watercolors were well known at the time. In that capacity Grover remained active in promoting the industrial arts movement and art teaching in America. However after “serving a sentence of 30 years in the publishing business,” Grover was ready to retire. Then a call from Hamilton Holt in 1926 changed his life.

The idea of a “Professor of Books” originated from Ralph Waldo Emerson, who wrote in his essay on books in 1856: “Meantime the colleges, while they furnish us with libraries, furnish no Professor of Books, and I think no chair is so much wanted.” Upon becoming the President of Rollins College, Holt saw the cultural possibilities in Emerson’s suggestion, and believed it suited his hope of making Rollins an ideal small liberal college. He made Grover his first faculty appointee as America’s first “Professor of Books.” Some years later Grover recalled “the thrill which I experienced when I came upon Emerson’s suggestion which was to change my life work and make my new vocation also an avocation. My imagination immediately took wings and I began to mull over the possibilities dormant in Emerson’s idea.” [16]

The idea of a “Professor of Books” originated from Ralph Waldo Emerson, who wrote in his essay on books in 1856: “Meantime the colleges, while they furnish us with libraries, furnish no Professor of Books, and I think no chair is so much wanted.” Upon becoming the President of Rollins College, Holt saw the cultural possibilities in Emerson’s suggestion, and believed it suited his hope of making Rollins an ideal small liberal college. He made Grover his first faculty appointee as America’s first “Professor of Books.” Some years later Grover recalled “the thrill which I experienced when I came upon Emerson’s suggestion which was to change my life work and make my new vocation also an avocation. My imagination immediately took wings and I began to mull over the possibilities dormant in Emerson’s idea.” [16]

At Rollins, Grover taught three courses through the Department of Books: the History of Books, Literary Personalities, and Recreational Reading. To avoid the formality of the conventional classroom, and secure closer and friendlier contacts with the students, Grover asked the carpenter to build him a large oval table, 14 by 6 feet, surrounded by 20 comfortable oak arm chairs. The walls of the room were hung with a score of pictures – framed pages of old books, block prints, lithographs, autograph portraits and letters. More than a thousand books in every literary field filled the shelves in the room. From this setting Grover made great personalities come alive, and for more than two decades he helped his students discover romance between the covers of good books, and establish reading habits that would last through their lives. The arrangement was so successful, Holt promoted it as the new Rollins Conference Course. This collaborative study method is still a cherished learning style at Rollins today.

Because of his literary interests and business background, Grover helped students publish the college’s first literary magazine Flamingo in 1927. He and William Yust established the Book-A-Year Club in 1933, which during the ensuing years generated steady revenues for the college library. Grover was also the editor of the Rollins’ Animated Magazine for more than two decades, and served as the librarian and vice president of the college. To recognize his achievement, the University of Miami and Rollins College awarded him honorary degrees in 1929 and 1949.

Besides being an accomplished academic, Grover was also very active in community affairs. He was a charter member of the University Club of Winter Park, and helped found the first bookstore in town named the “Bookery.” More notably, Grover played a leading role in the improvement of interracial relations during the early twentieth century. He served as a trustee of Bethune-Cookman College for some years. In 1930, he encouraged his wife Mertie Grover and Mrs. Clarence Vincent, wife of the pastor of the Congregational Church, to start a day nursery for children of black working mothers in Winter Park. When Mertie died in 1936, Grover asked that no flowers be sent to the funeral; instead funds were received toward the establishment of a children’s library on the west side of the town. In 1937, the Hannibal Square Associates was incorporated and Grover served for about ten years as its president. In that capacity he had raised $20,000 for the West Side Community Center, $2,500 for the Hannibal Square Memorial Library, and $13,000 toward the building of the Mary DePugh Nursing Home in Winter Park.

One of the enduring contributions Grover made to the central Florida community was the founding and development of the Mead Botanical Garden. Since he moved to the region in the 1920s, Grover had befriended Theodore L. Mead because of his interests in nature. When the renowned horticulturist passed away in 1936, Grover visited Mead’s ranch in Oviedo to see whether it could be converted into a botanical garden for Rollins College. Then John H. Connery, who grew up as one of Mead’s Boy Scouts and studied at Rollins in the 1930s, suggested the swamp by Pennsylvania Avenue in Winter Park. Upon exploring the site with Connery the next morning, Grover was so excited, that on the same afternoon he visited the Orlando real estate office of Walter Rose, a state senator and the owner of the property, and successfully persuaded him to donate the twenty acres for the proposed project. After that, he talked Orange County and the City of Winter Park into contributing additional properties; and moreover, his determination convinced R. F. Leedy, J. A. Treat and Mary Bartels to give their lands for the cause. [17] To develop the garden, Grover was also instrumental in securing two grants from the Works Progress Administration totaling more than $62,000. With strong local and federal support, the construction of the fifty-five acre park began on January 9, 1938, and Grover presided over the ground breaking ceremony. Since the official opening of the Mead Botanical Garden on January 15, 1940, Grover had served as its first president for ten years until he retired f rom Rollins College. Despite his retirement, Grover remained a lifelong supporter of the garden. He was still actively seeking funding for the park when he was in his nineties.

One of the enduring contributions Grover made to the central Florida community was the founding and development of the Mead Botanical Garden. Since he moved to the region in the 1920s, Grover had befriended Theodore L. Mead because of his interests in nature. When the renowned horticulturist passed away in 1936, Grover visited Mead’s ranch in Oviedo to see whether it could be converted into a botanical garden for Rollins College. Then John H. Connery, who grew up as one of Mead’s Boy Scouts and studied at Rollins in the 1930s, suggested the swamp by Pennsylvania Avenue in Winter Park. Upon exploring the site with Connery the next morning, Grover was so excited, that on the same afternoon he visited the Orlando real estate office of Walter Rose, a state senator and the owner of the property, and successfully persuaded him to donate the twenty acres for the proposed project. After that, he talked Orange County and the City of Winter Park into contributing additional properties; and moreover, his determination convinced R. F. Leedy, J. A. Treat and Mary Bartels to give their lands for the cause. [17] To develop the garden, Grover was also instrumental in securing two grants from the Works Progress Administration totaling more than $62,000. With strong local and federal support, the construction of the fifty-five acre park began on January 9, 1938, and Grover presided over the ground breaking ceremony. Since the official opening of the Mead Botanical Garden on January 15, 1940, Grover had served as its first president for ten years until he retired f rom Rollins College. Despite his retirement, Grover remained a lifelong supporter of the garden. He was still actively seeking funding for the park when he was in his nineties.

Grover passed away in Winter Park on November 8, 1965. His legacy lives on, as his portrait greets visitors to the Rollins College Archives, the West Side Community Center and the DePugh Nursing Home when they open their doors to local residents every morning, and in dazzling flowers in the Mead Garden blossom each spring.

– Wenxian Zhang

Guild, Clara Louise (1864-1945)

First Graduate of Rollins College

Miss Clara Louise Guild, a Central Florida educator during the early twentieth century, was not only a charter student, but also the first graduate of the Rollins College. Born on June 5, 1864, Clara Guild was a Boston native and daughter of William Augustus and Laura Jane (Barnes) Guild. A Harvard medical school graduate, William Guild was a Boston pharmacist for thirty years. In 1883, he decided for health reasons to retire in Florida. At that time, C. L. Guild had attended a Latin school and a girls’ high school in Boston for four years, and she was ready to enter Wellesley. Her sister Alice had just graduated from the Massachusetts Normal Art School and had intended to open an art studio in Boston, but decided to move to Florida with her family. Arriving in Winter Park, they found the city “was nothing but sand and pine trees… The streets were laid out but most of them were only wagon tracks thru the woods.” [18] The Guilds quickly befriended Dr. Edward Hooker (1834-1904), a fellow New Englander and the first pastor of the Winter Park Congregational Church, who was instrumental in the founding of the Rollins College and later became the first president of the newly established institution. On November 4 , 1885, recommended by Hooker, C. L. Guild entered Rollins as a charter student. Her sister Alice became an art instructor and later head of the Arts Department at Rollins, a position she held for some years until her poor eyesight forced her to retire.

Miss Clara Louise Guild, a Central Florida educator during the early twentieth century, was not only a charter student, but also the first graduate of the Rollins College. Born on June 5, 1864, Clara Guild was a Boston native and daughter of William Augustus and Laura Jane (Barnes) Guild. A Harvard medical school graduate, William Guild was a Boston pharmacist for thirty years. In 1883, he decided for health reasons to retire in Florida. At that time, C. L. Guild had attended a Latin school and a girls’ high school in Boston for four years, and she was ready to enter Wellesley. Her sister Alice had just graduated from the Massachusetts Normal Art School and had intended to open an art studio in Boston, but decided to move to Florida with her family. Arriving in Winter Park, they found the city “was nothing but sand and pine trees… The streets were laid out but most of them were only wagon tracks thru the woods.” [18] The Guilds quickly befriended Dr. Edward Hooker (1834-1904), a fellow New Englander and the first pastor of the Winter Park Congregational Church, who was instrumental in the founding of the Rollins College and later became the first president of the newly established institution. On November 4 , 1885, recommended by Hooker, C. L. Guild entered Rollins as a charter student. Her sister Alice became an art instructor and later head of the Arts Department at Rollins, a position she held for some years until her poor eyesight forced her to retire.

Following the “Yale Model,” Rollins in the mid-1880s established a traditional curriculum with stringent requirements in classical studies that was weighted heavily in the ancient languages of Latin and Greek. At that time the state’s public school system was so inadequate, few students were able to acquire a sufficient background in those subjects. Therefore most of the sixty-six charter students were enrolled in the preparatory Rollins Academy instead of the College. Since C. L. Guild was not adequately prepared in Greek, she had to spend an extra freshman year taking classical study courses in that subject. The classes she took included Greek Grammar, Greek Prose and Composition, Homer, Oedipus, Demosthenes, Rhetoric, Logic, Mathematics, Calculus, Geometry, Surveying, Physics, Mechanics, Biology, Botany and others. [19] Besides the rigorous liberal arts curriculum, Guild was able to enjoy an active social life on campus that included picnics and boating on Lake Virginia, even though girls were not allowed to go alone and rowing was absolutely prohibited on Sundays. While a Rollins student, she also lived through the yellow fever panic in 1888, when an outbreak occurred in Jacksonville and the state was quarantined, and all letters to the rest of country were thoroughly perforated and fumigated.

Finally in May 1890, she and Miss Ida May Missildine became the school’s first senior class, earning a Bachelor of Arts degree. Since their names were listed in alphabetical order, Guild was recognized as the first graduate of the Rollins College. After Francis Fleming (1841 – 1908), Governor of Florida, delivered Rollins’ first commencement speech, Guild read her graduation essay “ Elements of Weakness in Our Republic” during the ceremony, in which she proclaimed: “Our fathers who laid the corner-stone of this nation, had noble characters – hence this grand government. To preserve it in beneficence and nobleness, a higher average of intelligence, virtue and patriotism is indispensable.” [20]

Upon graduation, Clara Guild began to pursue a teaching career in the Winter Park school system. President Hooker wrote a personal letter of recommendation on her behalf: “Miss Clara L. Guild is a graduate of the classical course of ROLLINS COLLEGE of the class of 1890. She has been teaching the past year in Florida with excellent success. She is a member of the Congregational Church of Winter Park and is a lady of great excellence of character and life. She will be trusted and loved wherever she may be called to work and her influence will always be for the best things. Her appearance is excellent. Edward P. Hooker, President of Rollins College, and Pastor of Congregational Church, July 2nd, 1891.” [21]

Remaining single all her life and with dedication and hard work, Clara Guild moved steadily forward in her profession. During 1895-96, she became principal of the Winter Park Public School, and from 1896 to 1899, she was an instructor at a grammar school affiliated with the College. On May 23, 1898, Clara Guild received her M.A. degree from Rollins. Her thesis was suitably titled “The Child: the Centre of Education.” During the same year, she also founded the Alumni Association of Rollins College, served as first president, and was later awarded life membership of the organization. Entering the twentieth century, Guild had served as principal of the Sanford High School for thirteen years. In a re-appointment letter written by B. F. Whitner on May 15, 1912, the Secretary of Sanford Public School Board commented: “We want you to know that your unselfish, conscientious devotion to the duties of your position are appreciated by the Board and the patrons of the school generally, at their true value. We feel that the result that has been accomplished here, the development and advancement of our schools until they stand at the head of the list in this county, and second to none in the State, is due in large measure to your work and your influence.” [22]

After her tenure in Sanford, Guild became a professor of Latin and history at the Cathedral School in Orlando from 1920 to 1931. She later returned to Winter Park School before retiring in 1939 with more than four decades of educational work in Central Florida. Within the local community, Guild was also an active member of the Winter Park Women’s Club and the Fortnightly Club. On April 17, 1935, when Rollins celebrated its fiftieth anniversary, Clara Guild became the first alumnae to be awarded the Rollins Decoration of Honor. During the ceremony, Rollins President Hamilton Holt (1872-1951) remarked: “Clara Louise Guild, the greatest asset of any college is a good graduate. As our charter student, first graduate of Rollins and founder of the Rollins Alumni Association, you have set an example of loyalty and service to Rollins as well as to this community, that is an inspiration to all alumni who follow. It is a privilege, indeed, to bestow upon you the first Rollins Decoration of Honor to be given to an alumnus or alumna of Rollins College.” [23]

Clara Guild passed away on Tuesday, August 21, 1945 at her Winter Park home, 419 North Interlachen Avenue after struggling with a lingering illness. She was buried in Lowell, Massachusetts following a funeral service at the Carey Hand Funeral Home in Orlando, Florida.

– Wenxian Zhang

Guild, William A. (1827-1902)

Early Settler

William Augustus Guild was born in 1827 in Massachusetts. He was educated in the public school system of Lowell , Massachusetts. Guild completed high school and began working as a clerk in a drug store in Lowell in 1842. He continued working in the store for several years with the exception of three years he spent in the navy working as an apothecary. William also attended and graduated from Harvard Medical School. Later on in his life he moved to Boston where he worked as a pharmacist for thirty years. He married Laura Jane (Barnes) Guild and had two daughters, Alice E. Guild and Clara L. Guild.

William Augustus Guild was born in 1827 in Massachusetts. He was educated in the public school system of Lowell , Massachusetts. Guild completed high school and began working as a clerk in a drug store in Lowell in 1842. He continued working in the store for several years with the exception of three years he spent in the navy working as an apothecary. William also attended and graduated from Harvard Medical School. Later on in his life he moved to Boston where he worked as a pharmacist for thirty years. He married Laura Jane (Barnes) Guild and had two daughters, Alice E. Guild and Clara L. Guild.

William first came to Florida in 1883 in an effort to retire and improve his health. [24] During that year he bought twenty acres of land on the north shore of Lake Osceola. Guild went into the orange grove business and had twelve thousand orange trees planted on his property. He also built a large house that could accommodate approximately fifteen boarders. Guild was active in the development of Winter Park and was dedicated to the efficient running of his orange groves. [25] However, after his business suffered greatly during the Great Freeze of 1895, he became discouraged about the orange grove business. [26] In 1888 Williams entered the drug business in Sanford, Florida. He later moved back to his Winter Park home and continued working in the drug business. While in Winter Park, Guild also became close friends with Dr. Edward Hooker, the first pastor of the Winter Park Congregational Church and a New Englander.

William first came to Florida in 1883 in an effort to retire and improve his health. [24] During that year he bought twenty acres of land on the north shore of Lake Osceola. Guild went into the orange grove business and had twelve thousand orange trees planted on his property. He also built a large house that could accommodate approximately fifteen boarders. Guild was active in the development of Winter Park and was dedicated to the efficient running of his orange groves. [25] However, after his business suffered greatly during the Great Freeze of 1895, he became discouraged about the orange grove business. [26] In 1888 Williams entered the drug business in Sanford, Florida. He later moved back to his Winter Park home and continued working in the drug business. While in Winter Park, Guild also became close friends with Dr. Edward Hooker, the first pastor of the Winter Park Congregational Church and a New Englander.

While in Florida, his daughter, Alice E. Guild, who had recently graduated from the Massachusetts Normal Art School became an art instructor at Rollins College with the help and recommendation of Dr. Edward B. Hooker. Later she became the head of the Arts Department at Rollins College. Her sister, Clara Louise Guild, enrolled in the Rollins Academy for one year prior to entering Rollins College because she was thought unprepared for Greek studies. [27] After one year, Clara was admitted into the College and joined the Chi Omega Sorority. Clara Louise Guild, along with Ida May Missildine were the first individuals to graduate Rollins College with a Bachelor of Arts degree in May of 1890.

While in Florida, his daughter, Alice E. Guild, who had recently graduated from the Massachusetts Normal Art School became an art instructor at Rollins College with the help and recommendation of Dr. Edward B. Hooker. Later she became the head of the Arts Department at Rollins College. Her sister, Clara Louise Guild, enrolled in the Rollins Academy for one year prior to entering Rollins College because she was thought unprepared for Greek studies. [27] After one year, Clara was admitted into the College and joined the Chi Omega Sorority. Clara Louise Guild, along with Ida May Missildine were the first individuals to graduate Rollins College with a Bachelor of Arts degree in May of 1890.

William Augustus Guild died in 1902. He was not only one of the first settlers of Winter Park, but also the father of two influential individuals the College has had the pleasure of working with. Mr. Guild has been described as “a fine gentleman of the old school, an excellent type of America’s best citizenship and enjoys the esteem of all who come in contact with him.” [28] There is no doubt that his strength of character influenced both Clara and Alice, and thus had a positive impact on both the Winter Park and Rollins College communities.

– Kerem K. Rivera

- “Industry Loses Telephone Pioneer.” Sun Herald, October 19, 1978. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Fran Conklin, “Rollins College Organist to Play at Lincoln Center,” Orlando Sentinel – Florida Magazine, 22 March, 1964, 19-F. ↵

- Rollins College News Bureau, “Dr. Edwin Granberry- Rollins College” February 25, 1950. Box 45E, Olin Library, Rollins College, Winter Park, Florida. ↵

- Joseph M. Florida, Southern Writers (New York: LSU Press, 2006) p. 164-65. ↵

- Ibid., p 165. ↵

- Rollins College News Bureau, Trip to Czardis on New CBS Series,” 1959, Box 45E, Olin Library, Rollins College, Winter Park, Florida. ↵

- Courtlandt Berry, “Remember When: Edwin Granberry Wrote, Taught, Lived in City,” Winter Park Outlook, January 5, 1989, p.2. ↵

- “Raymond Greene Timeline.” Trustee File, 10B, Rollins College Archives. ↵

- Biographical Sketch on Rollins Graduates and Former Students: Raymond Greene. Trustee File, 10B, Rollins College Archives. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- “Raymond W. Greene: Class of 1923.” Trustee File, 10B, Rollins College Archives. ↵

- Alumni File: Wilhelmina Greene. 150E. Rollins College Archives. ↵

- Jean Yothers. “Something to Color,” Orlando Sentinel, Sunday March 19, 1961. ↵

- Edwin Grover, “The Fun of Professing Books,” Department of Archives and Special Collections, 45E, Olin Library, Rollins College, Winter Park, Florida. ↵

- Nick White, “Mead Garden Founder is 93: He Helps Park Rise from Swamp,” Winter Park Star, June 5, 1963. ↵

- Jane McCann, “Personalities of Winter Park,” n.p., December 7, 1937. ↵

- Clara L. Guild, Faculty and Alumni Files, 45E. Department of Archives and Special Collections, Olin Library, Rollins College, Winter Park, Florida. ↵

- Clara L. Guild, “Elements of Weakness in Our Republic,” Orange County Reporter (Orlando), June 5, 1890. ↵

- Guild, Rollins College Archives, 45E. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Clara L. Guild, Faculty and Alumni Files. Department of Archives and Special Collections, Olin Library, Rollins College, Winter Park, Florida. ↵

- “Memoirs of Florida,” State University System of Florida PALMM Project, 21 May 2009. http://fulltext.fcla.edu/cgi/t/text/pageviewer-idx?idno=SF00000009_0002_000;q1=SF00000009;seq=1327;cc=fhp;view=image;size=s;start=1;c=fhp. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Guild, Rollins College Archives. ↵

- “Memoirs of Florida,” State University System of Florida PALMM Project, 21 May 2009. http://fulltext.fcla.edu/cgi/t/text/pageviewer-idx?idno=SF00000009_0002_000;q1=SF00000009;seq=1327;cc=fhp;view=image;size=s;start=1;c=fhp. 538. ↵