H

Hanna, Alfred J. (1893-1978)

Teacher, Scholar & Academic Leader

A leading scholar on Florida history and specialist in Latin American affairs, Prof. A. J. Hanna had been associated with Rollins for more than six decades, likely the longest among all faculty members of the college community.

A leading scholar on Florida history and specialist in Latin American affairs, Prof. A. J. Hanna had been associated with Rollins for more than six decades, likely the longest among all faculty members of the college community.

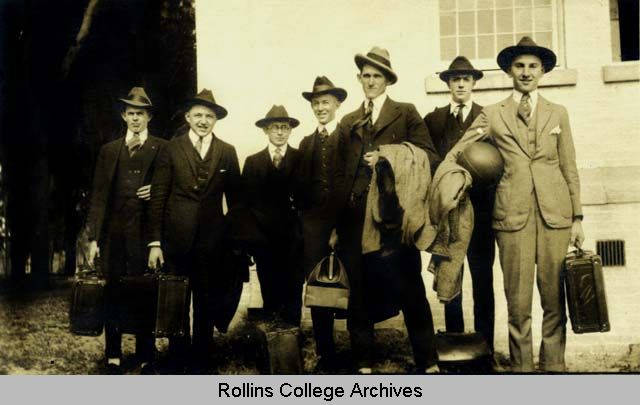

Born in Tampa on May 5, 1893, Alfred Jackson Hanna was the son of Josiah Calvin Hanna and Sarah Jackson Hanna. He was descended from a family of pioneers who settled in the Citrus County in 1840, before Florida was admitted to the Union. After graduating from the Hillsborough High School in 1911, Hanna attended the Eastman School and worked briefly in New York before enrolling at Rollins College in 1914. First appeared shy and reserved, Hanna quickly distinguished him on campus. In addition to his membership in Phi Alpha fraternity, he was the president of the Delphic Society, the undergraduate literary organization at Rollins. While a student, he also worked as an instructor for both Shorthand and Commercial English. More impressively, he had served as secretary to the faculty and to Dr. William Blackman, fourth president of Rollins College. During his junior year Hanna became the Editor-in-Chief of Sandspur, the student weekly newspaper, and in 1917, he worked as the editor of Tomokan, the inaugural volume of Rollins yearbook.

Upon graduation, Hanna became the registrar of the Business School and the president of the Rollins Alumni Association. After one year of leave of absence enlisting in the US Naval Reserve Force at the end of World War I, Hanna returned to Rollins and worked as assistant to president and assistant treasurer, and the editor of the inaugural issue of Rollins Alumni Record. However his real passion was in history, and in 1928-29 he was named an instructor in the History Department. A year later he became assistant professor, and in the following year he was again promoted, this time to associate professor. By 1938 Hanna had reached the rank of full professor and ten years later, he was named the first endowed chair of Weddell Professor of American History at Rollins, a title he held until his retirement in 1969.

To countless students, Hanna was a well-known and respected teacher. As one of the most popular faculty members on campus, he was sought for his ability to transpose dead facts of the past into a living adventure in the classrooms. An early supporter of Hamilton Holt’s Conference Plan of teaching at Rollins, Hanna believed that students benefit the best when they had a chance “to think for themselves and learn together with their teacher.” [1] When naming him as one of the “GREAT TEACHERS” of Rollins in 1955, one former student nominated Hanna “for his qualities of exacting scholarly research, and his ability to make history a living subject.” [2] Known both as a tough taskmaster and “father confessor”, Hanna had formed many lasting friendships and ties with Rollins graduates during the four decades of his teaching career. On the occasion of his retirement in 1969, the Rollins Board of Trustees proclaimed “By Dr. Hanna’s strict demand for academic excellence, he won for the College the praise of educators and the affection and respect of the students. From his tireless interest and devoted service, Rollins College stands out as a leader in Latin American relations and international understanding. His personal and professional life has attracted to Rollins College untold numbers of friends and supporters.” [3]

To many people outside of the Rollins community, Hanna was better known as a scholar who had written a number of books, mostly dealing with Florida history and Latin American affairs. As the editor of Rollins Sandspur, Tomokan and Alumni Record, Hanna had been a published writer since his days as a Rollins student. However he did not established himself as a historical scholar until the 1930s. His first major book, Flight into Oblivion ( Johnson Publishing, 1938 ) , was a well-researched and exciting tale of the flight of the Confederate Cabinet after the Southern defeat at the end of American Civil War. The book broke new ground, uncovered many new facts and was nicely received, including a favorable review in the New York Herald Tribune from Henry Steele Commager, one of America’s outstanding historians.

Hanna’s second major work, A Prince in Their Midst, was published by the University of Oklahoma Press in 1946. It documented the adventures of Achille Murat, the nephew of Napoleon I, who came to Florida after Napoleon’s defeat at Waterloo. In this book Hanna recounted the experience of this old world aristocrat and his efforts to find elusive success on Florida’s frontier. Also well received, Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings, Florida’s most prominent novelist, reviewed the book in the New York Herald Tribune.

When speaking on A. J. Hanna, it would be impossible not to mention his wife and scholarship companion. On July 5, 1941, after 12 years of courting, Hanna finally married Kathryn Abbey, a leading Florida historian and the love of his life. Receiving her BA, MA and PhD from Northwestern University, Abbey had been the chair of History Department at the Florida State University for 15 years. She agreed to marry Hanna, only after she learned the historical fact that he was actually two years older than she. Since then they worked happily together, published the Lake Okeechobee in 1948 and Florida’s Golden Sands in 1950, and embarked an incredible journey of collaborative scholarship.

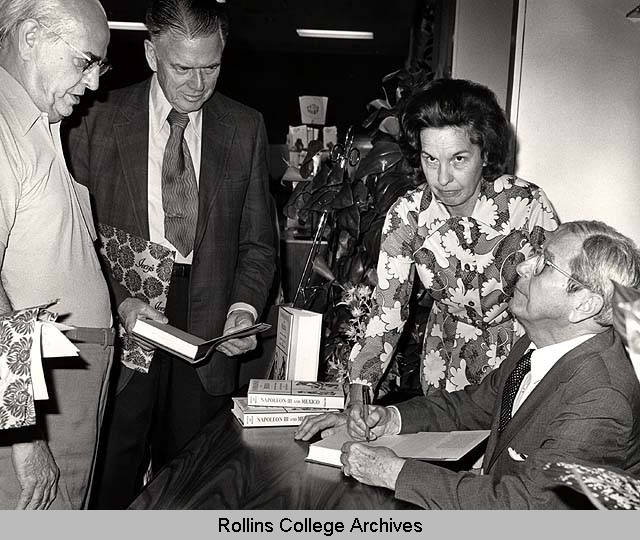

Hanna’s last major book also represented his most ambitious scholarly effort. Along with his wife Kathryn, Hanna spent over a quarter of a century researching and writing an account of Napoleon III’s incredible attempt to extend his empire into North America and how that effort failed because of America’s commitment to republic government in the new world. Published by the University of North Carolina Press in 1971, Napoleon III and Mexico: American Triumph over Monarch firmly established Hanna’s reputation as a leading scholar on the history of US-Mexico relations. [4] However not many people know that Hanna lost most his eyesight while working on this project, a great feat of courage and scholarly dedication. In addition, Hanna had collaborated with Novelist James B. Cabell to publish the St. Johns: a Paradise of Diversities (Farrar & Rinehart, 1943), an influential title in the Rivers of America Series. He also contributed to the Dictionary of American Biography, Dictionary of American History, and to a number of other leading historical journals.

Dedicated his life to the cause of preserving and making accessible the historical records of the state, Hanna developed the Union Catalog of Floridiana, a comprehensive collection of materials throughout the world relating to Florida. He was also responsible for the establishment of Florida Collection at Rollins, one of the best in the country. Along with Edwin Grover and William Yust, Hanna helped found the Book-A-Year Club in the 1930s, a library endowment fund at Rollins that grows with a current market value of over 3.2 million dollars. It is fair to say that without Hanna, there would not be the rare Florida Collection and Rollins Archives that we treasure so much today.

Hanna’s impact went far beyond his roles as a history teacher and scholar. During his years at Rollins, Hanna had acted as secretary or advisor to seven of its presidents. He organized the alumni association, founded and edited its magazine and raised money whenever needed. Actively involved in fund-raising for buildings, endowment, equipment and scholarships, Hanna was not only the chairman of the History Department and director of Inter-American Studies (1942-58), but also the first vice president (1951-69) and a member of the Rollins Board of Trustees (1969-78). According to Hamilton Holt, eighth president of Rollins: “In a long and varied experience in serving on committees, I have never found a man who is more efficient in, or devoted to his work than Fred Hanna. The Alumni of Rollins are to be congratulated on having such an ardent and devoted worker on behalf of their College.” [5]

Well known in international historical circles, Hanna was a member of a number of honorary societies in the U.S. and abroad. He was the former president of the Florida Historical Society, former director of the Southern Historical Association, chairman of the Latin American Division of the Florida State Chamber of Commerce, president of the Florida Audubon Society, and vice president of the Florida Academy of Sciences. He was also a member of the Authors Club of London, founding president of the Hispanic Institute of Florida. In addition, he was featured in Who’s Who in America, Who’s Who in American Education, and the Directory of American Scholars.

In recognition of his historical achievement, Hanna was decorated with Officer d’Academie, Palmes Universitaires by the French Government in 1935. The award was instituted in 1808 by Napoleon as a civil decoration and awarded to those who have especially distinguished themselves in connection with education, art, science or literature. In 1945, Hanna was awarded an honorary Doctor of Humanities from Rollins College; in 1953, he was presented the Centennial Award from the University of Florida for his “distinguished contribution in the field of letters, education and inter-cultural understanding”; and finally in 1977, for his contributions in the field of history, Hanna was presented the Award of Merit by the American Association for State and Local History.

When Hanna passed away in 1978, it had been specially requested that in lieu of flowers, contributions be made to the Rollins College Book-A-Year fund. As noted by Fred Hicks, then acting president of the College: “Dr. Hanna distinguished himself as a scholar, educator and administrator, and the College, its faculty and student body have benefited from his association,” as his “service to Rollins for the past 60 years has been an inspiration to many in the College community.” [6] Though a loss to Rollins, Central Florida and the world of scholarship, Hanna’s legacy has lived on, and the creation of A.J. Hanna Award in 2009 is probably the best way to honor the man who dedicated all his life to his alma mater and to the pursuit of historical knowledge.

– Wenxian Zhang

Hauck, Frederick Alexander (1894-1997)

Businessman and Philanthropist

Frederick Alexander Hauck was born on December 28, 1894 in Cincinnati, Ohio to Louis John and Frieda (Schmidt) Hauck. John was a well-known banker and businessman and Frederick was raised in a wealthy family. He was first educated in Cincinnati public schools, and then attended Franklin Preparatory School and studied at the University of Munich in Germany. Upon graduation, he began to work for the firm of Max Wocher and Sons, which produced surgical supplies and was quickly promoted to vice president. He served as chairman of the board from 1916 to 1937. He married Carolyn Russell Frear of Troy, New York on October 17, 1929. They had two daughters Alexandra and Frances.

Frederick Alexander Hauck was born on December 28, 1894 in Cincinnati, Ohio to Louis John and Frieda (Schmidt) Hauck. John was a well-known banker and businessman and Frederick was raised in a wealthy family. He was first educated in Cincinnati public schools, and then attended Franklin Preparatory School and studied at the University of Munich in Germany. Upon graduation, he began to work for the firm of Max Wocher and Sons, which produced surgical supplies and was quickly promoted to vice president. He served as chairman of the board from 1916 to 1937. He married Carolyn Russell Frear of Troy, New York on October 17, 1929. They had two daughters Alexandra and Frances.

Frederick’s father had been involved in the mining industry. Papers left behind by his father sparked his interest in the industry. [7] He became president and a stockholder of the Transversal Copper Mining Company. However the company experienced financial difficulties in the 1950s. As a result, Hauck traveled to Mexico to inspect his property. While visiting he collected borings from the mines and brought them back to Ohio where they were inspected. Rare metals were found and Hauck began researching and studying the materials. He became a well-known metallurgist and worked with the Bureau of Mines and the Atomic Energy Commission. [8]

Hauck purchased the Florida Ore Processing Company in Melbourne in an attempt to obtain heavy minerals from beach sand. Afterwards, he formed the Continental Mineral Processing Corporation in Sharonville , near Cincinnati after consulting Albert Einstein on the matter of mineral abstraction. [9] The facility allowed workers to separate minerals. The Continental Mineral Processing Corporation grew and four plants were established in Florida.

Frederick Hauck created a sizable personal fortune through his business dealings. With his business success, he turned to philanthropy, making large donations to educational institutions. His generosity earned him the nickname “ Mr. Cincinnati.” [10] Hauck donated to the University of Florida, Xavier University in Cincinnati, the Cincinnati Historical Society, and Rollins College among many others.

Hauck was a Winter Park resident for thirty years arriving in the 1940s. He built a home on Isle Sicily on Lake Maitland. [11] While in Winter Park he helped plan the bridge that connects the island to the mainland. He was also involved with Rollins through scientific research and financial contributions. He donated $10,000 to the Dubois Health Center for medical equipment, $2,150 towards Rollins’ $100,000 Latin American Scholarship Endowment goal, Casa Iberia and a $25,000 endowment along with a parking lot and building named after him to the East of Casa Iberia. Hauck also gave a $100,000 grant that allowed for the establishment of a Botanical Research Center. In February 1975 he established an annual honor scholarship for a student majoring in chemistry. Hauck married Sue Bradley of Maitland after the death of his wife Carolyne on October 27, 1977. Hauck received an honorary degree of Doctor of Laws from Rollins College on May 22, 1983.

Hauck was a Winter Park resident for thirty years arriving in the 1940s. He built a home on Isle Sicily on Lake Maitland. [11] While in Winter Park he helped plan the bridge that connects the island to the mainland. He was also involved with Rollins through scientific research and financial contributions. He donated $10,000 to the Dubois Health Center for medical equipment, $2,150 towards Rollins’ $100,000 Latin American Scholarship Endowment goal, Casa Iberia and a $25,000 endowment along with a parking lot and building named after him to the East of Casa Iberia. Hauck also gave a $100,000 grant that allowed for the establishment of a Botanical Research Center. In February 1975 he established an annual honor scholarship for a student majoring in chemistry. Hauck married Sue Bradley of Maitland after the death of his wife Carolyne on October 27, 1977. Hauck received an honorary degree of Doctor of Laws from Rollins College on May 22, 1983.

Hauck passed away in May 1997. His generosity and positive attitude permeated the many communities he was involved with. Winter Park was fortunate to have housed such a notable and kind personality.

– Kerem K. Rivera

Hellwege, Herbert (1921-2005)

Chemistry Professor

Herbert Elmore Hellwege received his early education from a technical gymnasium in Bustechude, Germany until 1939, when his schooling was cut short by the Nazi regime. Hellwege postponed his services to the military for half a year, during which time he worked for the “Arbeitssienst” (work corps) shoveling ditches. In 1939, Hellwege finally joined the German Air Force, where he received instruction on becoming an airplane pilot. Hellwege traveled throughout Europe, first to Norway, and then to Denmark and Prague, until he reached Italy, where Italian insurgents captured him and held him hostage. After a period of starvation, a group of New Zealand soldiers rescued Hellwege and sent him to a war camp near Rimini. In October 1945, after reaching the rank of second lieutenant, Hellwege made his departure from the services and continued his education at the University of Hamburg. There he majored in inorganic chemistry, and graduated with a doctorate degree in 1953.

Herbert Elmore Hellwege received his early education from a technical gymnasium in Bustechude, Germany until 1939, when his schooling was cut short by the Nazi regime. Hellwege postponed his services to the military for half a year, during which time he worked for the “Arbeitssienst” (work corps) shoveling ditches. In 1939, Hellwege finally joined the German Air Force, where he received instruction on becoming an airplane pilot. Hellwege traveled throughout Europe, first to Norway, and then to Denmark and Prague, until he reached Italy, where Italian insurgents captured him and held him hostage. After a period of starvation, a group of New Zealand soldiers rescued Hellwege and sent him to a war camp near Rimini. In October 1945, after reaching the rank of second lieutenant, Hellwege made his departure from the services and continued his education at the University of Hamburg. There he majored in inorganic chemistry, and graduated with a doctorate degree in 1953.

Directly after graduation, Hellwege married his childhood neighbor, Frieda Tennert, and together they moved to United States under the McCarran-Walter Act, a law providing immediate entry into the United States for natural scientists. Hellwege settled in New York City, where he worked as a chemist in a food and drug research laboratory. Within a year, Hugh McKean, president of Rollins College, recruited Hellwege to Rollins College, Winter Park, Florida. In 1954, Hellwege joined the faculty as assistant professor in chemistry without any previous teaching experience. Nevertheless, Hellwege offered innovative approaches to some of his courses, where he gave oral exams instead of multiple-choice  tests, and introduced radiochemistry and environmental chemistry courses into the curriculum. By 1959, after receiving a promotion to associate professor, Hellwege began his periodic visits to the Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL), where he investigated the “basic physical and chemical properties of the man-made transuranium elements.” [12] After completing his extensive research, Hellwege returned to Rollins, where he received the Arthur Vining Davis Fellowship and became the chair of the Department of Chemistry. During this time, Hellwege also became involved with the development of the soccer team, and acted as a charter member of Tau Kappa Epsilon Fraternity. According to an interview with Hellwege, being a part of the Rollins community, “[gave] him all that [he] ever wanted in life. It gave [him] an opportunity to do things outside college teaching,” such as being able to work as a clinical laboratory director and as a researcher for the cosmetics industry. [13] Hellwege retired from Rollins in 1985, and soon after traveled, took tai chi classes, learned how to sew, and took care of his ailing wife. [14]

tests, and introduced radiochemistry and environmental chemistry courses into the curriculum. By 1959, after receiving a promotion to associate professor, Hellwege began his periodic visits to the Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL), where he investigated the “basic physical and chemical properties of the man-made transuranium elements.” [12] After completing his extensive research, Hellwege returned to Rollins, where he received the Arthur Vining Davis Fellowship and became the chair of the Department of Chemistry. During this time, Hellwege also became involved with the development of the soccer team, and acted as a charter member of Tau Kappa Epsilon Fraternity. According to an interview with Hellwege, being a part of the Rollins community, “[gave] him all that [he] ever wanted in life. It gave [him] an opportunity to do things outside college teaching,” such as being able to work as a clinical laboratory director and as a researcher for the cosmetics industry. [13] Hellwege retired from Rollins in 1985, and soon after traveled, took tai chi classes, learned how to sew, and took care of his ailing wife. [14]

On November 15, 2005, Herbert Hellwege passed away. To honor the Professor, a memorial service was held at the Rollins College Knowles Memorial Chapel, and a Hellwege Scholarship fund, intended to provide stipends to students working on summer research projects with the chemistry faculty, was set up.

– Alia Alli

For further information concerning the life of Herbert E. Hellwege, please visit: http://lib.rollins.edu/olin/Archives/oral_history/Hellwege/Hellwegebiography.htm.

Henderson, Gus C. (1862-1917)

African-American Advocate

Gus C. Henderson (1862-1917) has been described as “ambitious and aspiring… proud of the prominence he has attained.” [15] The latter describes the manner in which Henderson led his life and conducted business.

Henderson was born on November 16, 1862, in Columbia County, located near Lake City, Florida. Henderson’s mother died when he was ten years old. As a result, he was left to fend for himself. He worked for low wages in an attempt to take care of himself. [16] He was a curious young man and had a great desire to learn. He studied by himself and remained in the Colombia County area until he reached the age of twenty. He tried his hand at being a farmer but decided to leave it behind to become a traveling salesman. Although he had some success as a salesman, he soon received a letter asking him to resign from the New York firm he had been working for for five months. [17] When a sked for an explanation, the firm stated that they had received threats from white salesmen for hiring an African American. Gus felt disheartened by this news. [18]

In 1886 he moved to the area that would later become Hannibal Square. Henderson decided to initiate a general printing and publishing company. In 1887 he encouraged the African American residents of Hannibal Square to support Loring Chase and Oliver Chapman, who advocated for the incorporation of Winter Park and Hannibal Square as one city. His efforts made the latter possible. Chapman and Chase showed gratitude towards their supporters by selling lots, renting land and providing employment to the African American community. [19] This helped secure many votes. Henderson also encouraged his community to vote for the first African American aldermen of Winter Park, Walter B. Simpson and Frank R. Israel.

On May 31, 1889, Henderson released the first issue of The Winter Park Advocate. This newspaper was one of two black-owned newspapers in Florida and the only newspaper in Winter Park read by both white and black residents. It remained in publication for approximately twelve years. Henderson later moved to Orlando, where he published the Florida Christian Recorder.Throughout his life, Gus Henderson advocated for voting rights and better education for African Americans, until his death in 1917. He faced many battles and obstacles, but his persistence allowed him to positively impact the Winter Park community at a time when the country, especially the South, was plagued by intense racial divisions.

-Kerem K. Rivera

Henkel, Miller A. (1848-1911)

Winter Park’s First Doctor

Miller A. Henkel was born on October 25, 1848 in Newmarket, Virginia, where his family emigrated from Germany in 1717 and received a land grant from William Penn. The first family member in America, Gerhard Henkel, created the First Lutheran Church in Philadelphia. Miller A. Henkel was born into a family of twelve children, many of which died from tuberculosis. [20] In 1842 Henkel received his medical degree from the University of Pennsylvania and practiced medicine for over twelve years in Winchester, Virginia. In 1883 he moved to Winter Park and became the town’s first physician.

Miller A. Henkel was born on October 25, 1848 in Newmarket, Virginia, where his family emigrated from Germany in 1717 and received a land grant from William Penn. The first family member in America, Gerhard Henkel, created the First Lutheran Church in Philadelphia. Miller A. Henkel was born into a family of twelve children, many of which died from tuberculosis. [20] In 1842 Henkel received his medical degree from the University of Pennsylvania and practiced medicine for over twelve years in Winchester, Virginia. In 1883 he moved to Winter Park and became the town’s first physician.

As a physician, Henkel vowed to fight tuberculosis, the disease that took his wife and three of his five children. He failed to find a cure for the disease, but managed to deduce that unpasteurized milk was a likely cause of the ailment. [21] He devoted himself to his job and refused to let his son follow in his footsteps and practice medicine. His son, Thomas, a charter student at Rollins College, instead went into real estate. Nevertheless, the younger Henkel helped his father by becoming a skilled pharmacist.

Dr. Henkel contributed the city’s first sidewalk on what was known as the Henkel Block. This sidewalk allowed easy access to the Henkel building, which housed both Miller and Thomas’ offices. This building was later torn down in 1952. He spent much of his time involved with municipal affairs. Henkel served as mayor of Winter Park from 1902-1906. Dr. Henkel actively supported the Winter Park Congregational Church, and appreciated the natural beauty of Central Florida. He owned over 200 acres of orange groves and planted oak trees along many city streets. [22] Dr. Henkel died of heart disease on May 30, 1911.

– David Irvin

Holt, Hamilton (1872-1951)

Eighth President of Rollins College

Journalist, social activist, politician, pacifist, and college president, Hamilton Holt shaped the image and mission of Rollins College during his twenty-four years of service as college president. A respected magazine editor prior to his tenure at Rollins College, Holt was a candidate for the United States Senate and respected proponent of international peace. Holt innovative theories on classroom learning transformed collegiate education and garnered Rollins College a national and international reputation.

Journalist, social activist, politician, pacifist, and college president, Hamilton Holt shaped the image and mission of Rollins College during his twenty-four years of service as college president. A respected magazine editor prior to his tenure at Rollins College, Holt was a candidate for the United States Senate and respected proponent of international peace. Holt innovative theories on classroom learning transformed collegiate education and garnered Rollins College a national and international reputation.

Hamilton Holt was born in Brooklyn, New York on August 19, 1872 to George Chandler Holt and Mary Louisa Bowen. He grew up in Spuyten Duyvil section of Manhattan. Holt received his Bachelor of Arts degree from Yale University in 1894. At Yale he studied economics and sociology, fields he pursued during postgraduate study at Columbia University between 1894 and 1897. In 1897 Holt joined the staff of The Independent as managing editor. [23] His career well in hand, Holt married Alexandria Crawford Smith in 1899 and his family grew to include four children: Beatrice (later, Beatrice Chadbourne), Leila (later Leila Rosenthal), John Eliot and George Chandler. Not much is written about Holt’s family life. It is clear he was able to balance domestic and career responsibilities as he made rapid strides at The Independent. Founded in 1848 by several Congregational Church laymen, including Holt’s grandfather Henry C. Bowen, the Independent was a weekly religious magazine created to promote antebellum abolitionism. After the Civil War, the magazine remained a progressive voice that expanded it focus to address political, social, and economic issues. In 1913 Holt became editor and owner. Under his ownership, The Independent absorbed the notable progressive weekly the Chautauquan and in 1916 merged with Harper’s Weekly. Contributor as well as editor, Holt wrote articles on a variety of subjects. Pursuing a vision of equality in the pages of The Independent, Holt printed a series of “lifelets” or personal stories that explored the lives ordinary Americans between 1902 and 1906. The series stressed a “bottom up” approach that addressed both the promise and challenges associated with life in the United States. The profiles published included a young Polish sweatshop woman, a Greek peddler, an Irish cook, a Swedish farmer, a German nurse, and a southern black woman. For subjects lacking formal education, Holt had their stories transcribed and read back for their approval prior to publication. More than seventy-five “lifelets” were published in the pages of The Independent. Holt collected sixteen of the short profiles in The Life Stories of Undistinguished Americans (1906). [24] Continuing his advocacy for diversity and acceptance, Holt along with other notable progressives such as W.E.B. Dubois, Ida B. Wells-Barnett, Jane Addams, Florence Kelley, John Dewey, Charles Darrow, and Mary McLeod Bethune founded the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in 1909.

Hamilton Holt was born in Brooklyn, New York on August 19, 1872 to George Chandler Holt and Mary Louisa Bowen. He grew up in Spuyten Duyvil section of Manhattan. Holt received his Bachelor of Arts degree from Yale University in 1894. At Yale he studied economics and sociology, fields he pursued during postgraduate study at Columbia University between 1894 and 1897. In 1897 Holt joined the staff of The Independent as managing editor. [23] His career well in hand, Holt married Alexandria Crawford Smith in 1899 and his family grew to include four children: Beatrice (later, Beatrice Chadbourne), Leila (later Leila Rosenthal), John Eliot and George Chandler. Not much is written about Holt’s family life. It is clear he was able to balance domestic and career responsibilities as he made rapid strides at The Independent. Founded in 1848 by several Congregational Church laymen, including Holt’s grandfather Henry C. Bowen, the Independent was a weekly religious magazine created to promote antebellum abolitionism. After the Civil War, the magazine remained a progressive voice that expanded it focus to address political, social, and economic issues. In 1913 Holt became editor and owner. Under his ownership, The Independent absorbed the notable progressive weekly the Chautauquan and in 1916 merged with Harper’s Weekly. Contributor as well as editor, Holt wrote articles on a variety of subjects. Pursuing a vision of equality in the pages of The Independent, Holt printed a series of “lifelets” or personal stories that explored the lives ordinary Americans between 1902 and 1906. The series stressed a “bottom up” approach that addressed both the promise and challenges associated with life in the United States. The profiles published included a young Polish sweatshop woman, a Greek peddler, an Irish cook, a Swedish farmer, a German nurse, and a southern black woman. For subjects lacking formal education, Holt had their stories transcribed and read back for their approval prior to publication. More than seventy-five “lifelets” were published in the pages of The Independent. Holt collected sixteen of the short profiles in The Life Stories of Undistinguished Americans (1906). [24] Continuing his advocacy for diversity and acceptance, Holt along with other notable progressives such as W.E.B. Dubois, Ida B. Wells-Barnett, Jane Addams, Florence Kelley, John Dewey, Charles Darrow, and Mary McLeod Bethune founded the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in 1909.

Promoting racial equality was not the only goal Holt supported in print and action. Holt also championed international peace in the pages of The Independent. In 1907 Holt attended the Hague Peace Conference. Holt’s perspective on peace stressed engagement and dialogue. In 1907 he stated, “Disarmament cannot logically precede political organization, for until the world is politically organized there is no way, except by force of arms, by which a nation can assure its rights. [25] He further clarified the need for a centralized body to promote peace in 1911, when he wrote in an issue of World’s Work, “Let us add to the Declaration of Independence, a Declaration of Interdependence… Let the United Nation succeed the United States.” [26] Holt engagement on the international stage was varied, he was founding member of the Italy-America Society, the Netherlands American Foundation, American-Scandinavian Foundation, the Greek-American Club and the Friends of Poland. In the aftermath of the First World War, he became a strong supporter of Woodrow Wilson’s League of Nation proposal. He attended the 1919 Paris Peace Conference and later toured the United States promoting U. S. participation in the league. One article in The Independent warned, “If the covenant… is defeated, the nations cannot go for ward on an orderly basis of international cooperation, but must sink back to the old era of nationalistic competition, with its mutual hates, suspicions, and intrigues, its colossal armaments and inevitable wars.” [27] Holt helped found the League of Nations Non-Partisan Association and would later serve as director of the Woodrow Wilson Foundation. In 1921, Holt stepped down as editor of The Independent, becoming a consultant. He maintained his peace activism as he lectured for the American branch of the International Conciliation and World Peace Foundation and was one of the honorary directors of World Federalist USA. Holt’s efforts to promote peace garnered accolades and commendations from governments around the world. He was member of the Japanese Order of the Sacred Treasure, an officer of the Greek Order of George I, a member of the French Order of Public Instruction, a knight in the French Legion of Honor, a member of the Order of the Crown of Italy, a knight in Polonia Restituta, and a knight of the Swedish North Star.

In 1924, Holt was the Democratic Party’s pick for special election to fill the United State Senate seat for Connecticut. He was soundly defeated by Republican Hiram Bingham despite strong support from liberal voters in the state. [28] After this defeat, Holt was approached to become president of Rollins College by Irving Bacheller. A frequent contributor to The Independent and noted author, Bacheller served as a college trustee and offered Holt the position. Holt accepted the challenge later recalling, “I had no special qualification for the position. But from observation in many colleges and from my own experiences I had acquired definite idea about teaching which I longed to put into practice.” [29] Holt tenure at Rollins emphasized breaking down the tradition of aloof professor providing a canned lecture. He explained, “I objected to the lecture system. I agreed with the young man who described it as a process whereby the content of the professor’s notebook are transferred by means of a fountain pen to the student’s notebook without having passed the mind of either.” [30] Holt approach to education stressed a new system called the “conference plan.” This plan emphasized one-on-one interaction between professor and student. The goal was to allow students to work to better their minds with the guidance of

In 1924, Holt was the Democratic Party’s pick for special election to fill the United State Senate seat for Connecticut. He was soundly defeated by Republican Hiram Bingham despite strong support from liberal voters in the state. [28] After this defeat, Holt was approached to become president of Rollins College by Irving Bacheller. A frequent contributor to The Independent and noted author, Bacheller served as a college trustee and offered Holt the position. Holt accepted the challenge later recalling, “I had no special qualification for the position. But from observation in many colleges and from my own experiences I had acquired definite idea about teaching which I longed to put into practice.” [29] Holt tenure at Rollins emphasized breaking down the tradition of aloof professor providing a canned lecture. He explained, “I objected to the lecture system. I agreed with the young man who described it as a process whereby the content of the professor’s notebook are transferred by means of a fountain pen to the student’s notebook without having passed the mind of either.” [30] Holt approach to education stressed a new system called the “conference plan.” This plan emphasized one-on-one interaction between professor and student. The goal was to allow students to work to better their minds with the guidance of  the professor. This new approach required the college limit enrollment and recruit professors that would function in this new cooperative model. Holt’s view on professors was clear, he explained, “There are two kinds of professors, one the research man, draws his inspiration from learning; the other, the teacher, draws his from life. The first is a great scholar, the second a beloved teacher…. To my way of thinking it is more important for the college to have good teachers than good research men who may turn out to be teachers.” [31] Holt’s unorthodox approach to professorship was reflected in an equally strong sense of what kind of student he believed Rollins should come to Rollins. He dismissed the student that regurgitates on command. Instead, he emphasized that faithfulness and the ability to improve through effort the best qualifications for a Rollins student. [32] Under Holt, the college advocated that students have an eight-hour work day broken into four two-hour periods. Three periods were dedicated to “work of the mind under a professor in a classroom,” the fourth to activities which may range from working to pay tuition to rehearsing for the arts. [33]

the professor. This new approach required the college limit enrollment and recruit professors that would function in this new cooperative model. Holt’s view on professors was clear, he explained, “There are two kinds of professors, one the research man, draws his inspiration from learning; the other, the teacher, draws his from life. The first is a great scholar, the second a beloved teacher…. To my way of thinking it is more important for the college to have good teachers than good research men who may turn out to be teachers.” [31] Holt’s unorthodox approach to professorship was reflected in an equally strong sense of what kind of student he believed Rollins should come to Rollins. He dismissed the student that regurgitates on command. Instead, he emphasized that faithfulness and the ability to improve through effort the best qualifications for a Rollins student. [32] Under Holt, the college advocated that students have an eight-hour work day broken into four two-hour periods. Three periods were dedicated to “work of the mind under a professor in a classroom,” the fourth to activities which may range from working to pay tuition to rehearsing for the arts. [33]

Holt’s commitment to teaching innovation was given national prominence in 1931 when he invited numerous educators to campus to participate in curricular conference. Not without controversy, the Rollins Educational Conference brought together national experts on educations. Indeed, the conference’s emphasis on student desire challenged commonly held assumptions by conference attendees. Dr. J.K. Hart of Vanderbilt warned against framing curricula to reflect the “adolescent interests” of students. [34] Discussion between scholars from across the country, including schools such as Columbia, Sarah Lawrence, Vanderbilt, and Cornell touched on subject as diverse as the meaning of liberal arts and what effort should be taken to bridge the gap between practical concerns and traditional subject matter. Hosted by John Dewey, the recommendations from the conference were integrated into the college’s conference plan, cementing the school’s reputation as innovative teaching institution. [35]

Holt’s vision for Rollins community shaped not only curriculum, students and faculty, but the cultural experience of the region. Holt promoted the arts and humanities in numerous ways. In 1926, he created the Animated Magazine at Rollins College, a live program modeled on a magazine that brought contributors (speakers) on a variety of subjects to the College every February. Drawing on his contacts, Holt was able to draw notable figures to the College to participate in the magazine, among them actress Mary Pickford, novelist Faith Baldwin, and RCA chairman David Sarnoff. Holt served as editor and chief for the Animated Magazine program, often sitting on stage with giant pencil and eraser to edit verbose speakers. [36] Programs such as the Animated Magazine, WPRK, and the Theatre Department’s production made Rollins a prime cultural attraction in Central Florida. Holt support for traditional school activities were also well known. He attended student activities, invited students to his home on regular basis and advocated for student-faculty collaboration. Holt’s legacy on campus extends to the physical plant. Rollins’ architectural style shifted from it original New England inspired structures to the Spanish Mediterranean style when Holt hired architect to design Rollins Hall in 1930. Holt’s aesthetic transformation continued with the construction of Mayflower and Pugsley Halls and the chapel theatre complex. In addition, Holt acquired a home for Dean of Chapel, and several other off-campus houses, including a beach house called “The Pelican” at New Smyrna Beach. [37]

Holt’s vision for Rollins community shaped not only curriculum, students and faculty, but the cultural experience of the region. Holt promoted the arts and humanities in numerous ways. In 1926, he created the Animated Magazine at Rollins College, a live program modeled on a magazine that brought contributors (speakers) on a variety of subjects to the College every February. Drawing on his contacts, Holt was able to draw notable figures to the College to participate in the magazine, among them actress Mary Pickford, novelist Faith Baldwin, and RCA chairman David Sarnoff. Holt served as editor and chief for the Animated Magazine program, often sitting on stage with giant pencil and eraser to edit verbose speakers. [36] Programs such as the Animated Magazine, WPRK, and the Theatre Department’s production made Rollins a prime cultural attraction in Central Florida. Holt support for traditional school activities were also well known. He attended student activities, invited students to his home on regular basis and advocated for student-faculty collaboration. Holt’s legacy on campus extends to the physical plant. Rollins’ architectural style shifted from it original New England inspired structures to the Spanish Mediterranean style when Holt hired architect to design Rollins Hall in 1930. Holt’s aesthetic transformation continued with the construction of Mayflower and Pugsley Halls and the chapel theatre complex. In addition, Holt acquired a home for Dean of Chapel, and several other off-campus houses, including a beach house called “The Pelican” at New Smyrna Beach. [37]

Holt’s accomplishments as college president did not come without controversy. In 1933 Holt fired John Rice, a former Rhodes Scholar hired in 1930 to teach Greek. Rice’s short tenure at Rollins was highlighted by his unorthodoxy classroom technique and his discussion non-Greek subject such as sex and politics. Rice’s behavior alienated a large segment of the Rollins community prompting his dismal. Yet, Holt’s decision sparked concerns about academic freedom and led to an American Association of University Professor investigation. Moreover, when several faculty members objected to his decision, he terminated those professors and the dismissed faculty banned together to create Black Mountain College in Asheville, North Carolina. Holt faced other challenges as well. Holt’s longstanding support for diversity was challenged at Rollins as he was forced to suspend the 1947 homecoming football game with Ohio Wesleyan over the participation of African-American player and was initially blocked from awarding Mary McLeod Bethune an honorary degree.

Holt’s accomplishments as college president did not come without controversy. In 1933 Holt fired John Rice, a former Rhodes Scholar hired in 1930 to teach Greek. Rice’s short tenure at Rollins was highlighted by his unorthodoxy classroom technique and his discussion non-Greek subject such as sex and politics. Rice’s behavior alienated a large segment of the Rollins community prompting his dismal. Yet, Holt’s decision sparked concerns about academic freedom and led to an American Association of University Professor investigation. Moreover, when several faculty members objected to his decision, he terminated those professors and the dismissed faculty banned together to create Black Mountain College in Asheville, North Carolina. Holt faced other challenges as well. Holt’s longstanding support for diversity was challenged at Rollins as he was forced to suspend the 1947 homecoming football game with Ohio Wesleyan over the participation of African-American player and was initially blocked from awarding Mary McLeod Bethune an honorary degree.

Hamilton Holt’s vision remains a powerful touchstone for the college today. His ability to take the struggling liberal art institution in 1925 and transform it into a nationally and international known educational leader remains the standard by which the college measure its efforts today.

– Julian Chambliss

Hooker, Edward Payson (1834-1904)

First President of Rollins College

Born on July 2, 1834 in Poultney, Vermont to the agrarian Thomas and Betsey Hooker, Edward Payson Hooker descended from such notable individuals as the congregational minister Thomas Hooker and his patriotic grandfather and uncle, both of whom had served in the Revolutionary War. In 1835 Thomas Hooker moved his family (his wife, Edward, and five older siblings) to neighboring Castleton, owing to the town’s advanced educational opportunities. Edward Hooker graduated from school at the Castleton Seminary in 1851, having taken courses in Latin, Greek, and mathematics. The same year, Hooker entered Middlebury College with his brother, David, and graduated five years later with an Artium Baccalaureatus degree. Upon completion of his A.B., the college awarded Hooker a one-year fellowship in mathematics, which allowed him time to pursue graduate studies as he taught. Hooker’s life-long interests in classical education and religion reflected these early experiences.

Born on July 2, 1834 in Poultney, Vermont to the agrarian Thomas and Betsey Hooker, Edward Payson Hooker descended from such notable individuals as the congregational minister Thomas Hooker and his patriotic grandfather and uncle, both of whom had served in the Revolutionary War. In 1835 Thomas Hooker moved his family (his wife, Edward, and five older siblings) to neighboring Castleton, owing to the town’s advanced educational opportunities. Edward Hooker graduated from school at the Castleton Seminary in 1851, having taken courses in Latin, Greek, and mathematics. The same year, Hooker entered Middlebury College with his brother, David, and graduated five years later with an Artium Baccalaureatus degree. Upon completion of his A.B., the college awarded Hooker a one-year fellowship in mathematics, which allowed him time to pursue graduate studies as he taught. Hooker’s life-long interests in classical education and religion reflected these early experiences.

Hooker married his first wife, Annah Baxter, on November 9, 1857. The marriage lasted eight years until Annah Hooker died from illness in Castleton in November 1869. In 1858, Hooker received his Master of Arts degree from Middlebury, became a member of Phi Beta Kappa and Chi Psi, and entered the Andover Theological Seminary, from which he received a bachelor’s degree in 1861. That year, Hooker became an ordained pastor of the Mystic Congregational Church in Medford, Massachusetts. Hooker then assumed the position of pastor for the Middlebury Congregational Church on September 14, 1870. One year later, on September 2, Hooker married Elizabeth Mary Muzzy with whom he had six children: Elizabeth Robbins, Stuart Van Renselaer, Emily Griswold, Edward Clarendon, Mary Stuart, and David Ashley. All of Hooker’s children would later attend Rollins College.

Hooker served as a trustee of Middlebury College in 1876 (until his resignation ten years later) and earned his Doctoral degree from the institution in 1881. Hooker dutifully carried out his pastoral responsibilities, taught, and held positions on trustee boards throughout his life, demonstrating a commitment to faith, education, and community.

The first development regarding a movement to establish a college in Florida began in 1883 with Hooker’s move to Winter Park. Hooker arrived in Florida with the intention of improving his poor health in the warm climate. Hooker seconded Frederick Wolcott Lyman’s proposal to found the school on January 15, 1884, when he discussed the project in a sermon to his congregation. In February, Hooker helped organize the Winter Park Congregational Church, which met the next month and requested that Hooker prepare a paper on the condition of the public school and higher educational systems in Florida (which he presented on January 28, 1884). The congregation decided upon Winter Park as the location for the school in 1885 and selected Holt as the president of the faculty. The president secured funding (with himself receiving a salary of one thousand dollars for the first year), and taught courses in logic, ethics, philosophy, and the Bible. The college opened on schedule on November 4, 1885, with fifty-three students and twenty-five visitors. As a result of the lack of adequate primary school facilities in the area, the school initially provided preparatory education. Hooker also emphasized the importance of physical education. Thus, the courses offered in the gymnasium became an important part of the campus experience. Owing to his great respect for the northern curriculum, Hooker designed Rollins around classical education, encouraged a standard of grading based upon daily participation in class (rather than exams), and adopted the entrance requirements promoted by the President of Harvard.

Hooker served as a charter trustee, college pastor, and president of Rollins until his resignation in 1892. During that time, Hooker managed the various challenges of a new school, such as financial difficulties and the relative obscurity of the institution to New Englanders. He even went as far as personally housing a struggling student threatened with expulsion. Hooker also expressed interest in the community outside of Rollins, endeavoring for the improvement in the educational conditions of the Seminole. He described the subsequent changes in Winter Park, the “wonderful transformation of this hill from an unbroken waste, and the crowning of these slopes with these comely buildings, as in a night,” as a “grand enterprise.” [38]

Hooker served as a charter trustee, college pastor, and president of Rollins until his resignation in 1892. During that time, Hooker managed the various challenges of a new school, such as financial difficulties and the relative obscurity of the institution to New Englanders. He even went as far as personally housing a struggling student threatened with expulsion. Hooker also expressed interest in the community outside of Rollins, endeavoring for the improvement in the educational conditions of the Seminole. He described the subsequent changes in Winter Park, the “wonderful transformation of this hill from an unbroken waste, and the crowning of these slopes with these comely buildings, as in a night,” as a “grand enterprise.” [38]

After his retirement, Hooker continued to demonstrate his strength of character. In 1893 a series of storms sank the ship City of Savannah, aboard which Hooker and two of his children traveled, off the Florida Pan Shoals. During the crisis Hooker led prayer services and insisted on disembarking from the wreckage last, after several days of hardship. Hooker suffered severe injuries as a result of the accident and never fully recovered his health. In 1898 he resigned as pastor of the Congregational Church and retired to Marshfield, Massachusetts. Hooker died of nephritis on November 29, 1904. At Hooker’s memorial service, Loring Augustus Chase described him as a “man of commanding presence with a large body, a noble head, a handsome face illumined by a kindly smile, reflecting his sunny disposition.” [39] Hooker was a Republican, [40] had great skill as an orator, “intellectual vigor,” [41] and strong piety. Additionally, he authored Memorial of the Life, Character and Word of the Rev. Joseph Steele, published in Middlebury, 1874. The dedication of Hooker Hall in 1937, as well as the Hooker Educational Building (which replaced the original church and Hooker Memorial in 1940), serves to commemorate his contribution to Winter Park and Rollins College.

– Angelica Garcia

- “Dr. Alfred J. Hanna,” Winter Park Sun Herald, February 18, 1960. ↵

- Alfred J. Hanna, Faculty, Staff and Alumni Files, 45 E. Department of Archives and Special Collections, Olin Library, Rollins College, Winter Park, Florida. ↵

- “Hanna: A Legend in His Time,” Rollins College Alumni Record, 55.3 (Spring 1978): ↵

- Jack C. Lane, “Alfred J. Hanna: Scholar,” Rollins College Alumni Record, 55.3 (Spring 1978): 3. ↵

- “Concerning A. J. Hanna,” Rollins College Alumni Record, 8.2 (June 1931): 11. ↵

- Randy Xenakis, “Rollins Professor Emeritus Dr. Alfred J. Hanna Dead at 85,” Rollins News 1978, 45E. Department of Archives and Special Collections, Olin Library, Rollins College, Winter Park, Florida. ↵

- Ben L. Kaufman, “1894-1997 Frederick Alexander Hauck,” The Cincinnati Enquirer, Pg. A01, May 11, 1997. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ed Hayes. “ With Vision and Gumption for All,” Sentinel Sunday Magazine, pg. 6, April 26, 1981. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- “Rollins Professor Spends Sabbatical Year With Alummnus,” The Alumni Record, Winter 1983. ↵

- Herbert Hellwege, Interviewed by Wenxian Zhang, and Jack Lane. Rollins Oral History Archive. May 19, 2005. ↵

- Amy C. Rippel, “Rollins Scientist Herbert Hellwege Served as Role Model for Students,” Orlando Sentinel, November 21, 2005. ↵

- Barbara White, “Gus C. Henderson: Hard working and determined – He brought the news to Winter Park.” Winter Park Public Library. http://archive.wppl.org/wphistory/ghenderson.html ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Joey Feltus. “He prescribed Pills, Potions for Winter Park’s Pioneers.” Sentinel Star, August 14, 1976. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- S. J. Woolf, “Dr. Holt Looks at Education and Youth,” New York Times, August 17, 1947. ↵

- Lawrence J. Oliver, “Deconstruction or Affirmative Action: The Literary-Political Debate over the Ethnic Question,” American Literary History 3 (Winter 1991): 799-800. ↵

- Current Biography, 1947, The H.W. Wilson Company. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- “Dr. Hamilton Holt, Educator, 78, Dies,” New York Times, April 27, 1951 ↵

- S.J. Woolf, “Dr. Holt Looks at Education and Youth,” New York Times, August 17, 1947. ↵

- S.J. Woolf, “Dr. Holt Looks at Education and Youth,” New York Times, August 17, 1947. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- “Opposes Curricula On Pre-Student Ideas,” New York Times, January 21, 1931. pg 23. ↵

- Gayle and Steve Rajtar, “A Different Breed of College President: Hamilton Holt’s Nonconformist Belief Set Rollins on a Path to Excellence,” Winter Park Magazine (June 2009): 86. ↵

- Maurice O’ Sullivan and Jack C. Lane, “My dear Mrs. Baskin”: Majorie Kinnan Rawlings and Hamilton Holt,” The Majorie Kinnan Rawlings Journal of Florida Literature Vol. 17 (2009): 3. ↵

- Jack Lane, Rollins College: A Pictorial History (Rollins College, 1980): 54. ↵

- Loring A. Chase, “Reverend E.P. Hooker: Paper Read by Loring A. Chase at Memorial Services in Congregational Church, Winter Park, Sunday, December 11, 1904,” Department of Archives and Special Collections, Box 20A-C: 1 of 4, Olin Library, Rollins College, Winter Park, Florida. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Margery C. Hooker, Correspondence from Elizabeth R. Hooker to Mrs. Lehmen, June 28, 1960, ibid. ↵

- Anonymous Rollins Benefactor quoted in, “Edward Payson Hooker: 1834-1904,” Rollins Alumni Record. ↵