M

Martin, John (1864-1956)

Educator & Lecturer of International Relations

John Martin was born on May 13, 1864 in Lincoln, England to John and Ann Martin. He was educated in English public schools. Public schools, in the English sense, refer to privately operated secondary schools that oftentimes require tuition, as opposed to the American notion of public schools, which are funded with taxpayer revenue. After Martin attended the National Normal School in London from 1883 through 1884 he obtained the Queen’s (Victoria) Scholarship, and for the next two years taught in the London public schools. In 1889 Martin earned his Bachelors in Science from the University of London. In 1894 he became professor at the East London Technical College, where he remained there until 1897.

John Martin was born on May 13, 1864 in Lincoln, England to John and Ann Martin. He was educated in English public schools. Public schools, in the English sense, refer to privately operated secondary schools that oftentimes require tuition, as opposed to the American notion of public schools, which are funded with taxpayer revenue. After Martin attended the National Normal School in London from 1883 through 1884 he obtained the Queen’s (Victoria) Scholarship, and for the next two years taught in the London public schools. In 1889 Martin earned his Bachelors in Science from the University of London. In 1894 he became professor at the East London Technical College, where he remained there until 1897.

While in England, Martin became a member of the executive committee of the Fabian Society. The Fabian Society was comprised of prominent individuals interested in social reform. Fabian members included George Bernard Shaw, Sidney and Beatrice Webb and James Ramsay McDonald. Martin lectured at the People Palace in London where working men and women went to study.

Martin came to the United States in 1898 on a lecture tour. Shortly after arriving, Martin made up his mind to move to the states. In 1900 he married Prestonia Mann. Together, they established a home in Staten Island, New York. They also owned a home in the Adirondacks, Keene, New York where they hosted many prominent individuals including H.G. Wells and Maxim Gorky. Gorky, a Russian author, wrote his short novel, “Mother”, considered his best work by many Russian critics, while staying in the Martin residence. [1]

Martin spent many years involved in the New York education system. From 1900 to 1902 he became a director for the League for Political Education. In 1903 he became a naturalized U.S. citizen. From 1908 to 1916 Martin held several positions in New York City including director of the City Housing Corporation, member of the New York Board of Education, member of Woodrow Wilson’s pre- nomination campaign and a free lance writer and lecturer. During his time in New York Martin became heavily interested in adult education. [2]

In 1928 Martin moved to Winter Park, Florida. The following year he began working at Rollins College, and the connection lasted until his death in 1956. During his time at the college he served as a visiting professor, conference leader, lecturer and consultant on international relations. He focused on international problems especially those dealing with peace and war. He was known throughout Florida as a great lecturer. His lectures, which were held every Thursday and dealt with America’s foreign and domestic policies became so popular with students and residents, that the programs were moved to the Annie Russell Theater, then to the Congregational Church and finally to the local high school auditorium to accommodate the growing audience. [3] For his accomplishments, he received an honorary degree (L.L.D) from Rollins on February 24, 1936.

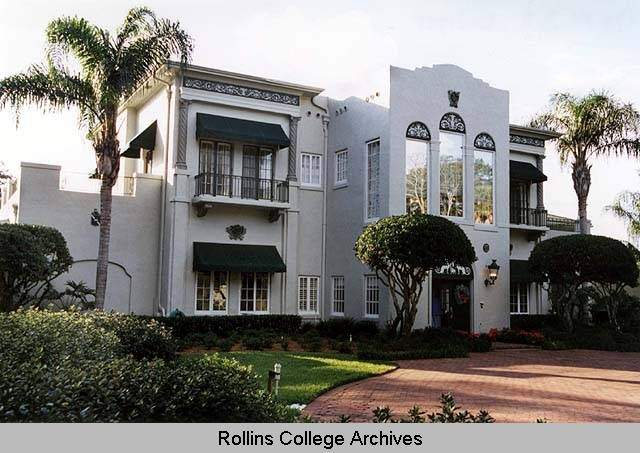

At his farewell celebration the audience passed a resolution asking Martin to continue his work. [4] John Martin died on April 6, 1956 in Winter Park, Florida. Martin willed his home to Rollins. It was later used as the College conservatory of music. There was no doubt that Martin was a thinker and innovator. He greatly influenced the way people thought about international problems.

– Kerem K. Rivera

Martin, Prestonia Mann (1862-1945)

Notable Author

Prestonia Mann Martin was born in 1862 in New York City to Dr. John Preston and Ann Rebecca Furman Mann. Her father was a prominent New York physician and a relative of the well-known Horace Mann, a pioneer in the field of public education. [5] While in New York City, Prestonia attended the Concord School of Philosophy at Concord, Massachusetts. There, she met and studied with individuals such as Ralph Waldo Emerson and Walt Whitman. Prestonia frequently visited the Adirondack Mountains with her father. She often visited the Thomas Davidson’s “School for the Cultural Sciences” at Keene in the late 1880s.

After her parent’s death, she married John Martin in 1900. Martin later became a lecturer and a consultant on International Relations at Rollins College in Winter Park, Florida from 1929 to 1951. She also moved to Keene, New York where she established a summer home called Summer Brook. Each summer, for twenty years, she invited fifteen to twenty five prominent individuals to live on her estate. The purpose of living on the estate was to create a just and cooperative society. There were three rules at Summer Brook. First, each person had to perform two hours of manual labor per day. Second, each person must be willing to share all their knowledge with the community.

Third, the living expenses were to be shared equally with the community. [6] Martin was described by John Spargo in a 1906 articles as, “an American lady of culture and wealth, with profound faith in the social ideals of the Collectivists.” [7] Her project, according to Spargo, aimed to “rekindle the spirit of social enthusiasm for which the famous Brook Farm stood in the days of Ripley, Greeley, Hawthorne, Margaret Fuller and others– that famous group of earnest men and women who embraced the teachings of the gentle French Utopist, Charles Fourier.” [8]

Prestonia gained most of her fame from her book Prohibiting Poverty. The book was written in 1932 during The Great Depression. It proposed that in order to solve the problem of poverty and unemployment all sixteen to twenty four year old Americans had to enlist in a labor army. This labor army would provide the rest of Americans with all the basic goods and services needed and would eliminate the need to buy or sell using money. [9] While her theory seems impractical it was highly praised by first lady, Eleanor Roosevelt.

Prestonia gained most of her fame from her book Prohibiting Poverty. The book was written in 1932 during The Great Depression. It proposed that in order to solve the problem of poverty and unemployment all sixteen to twenty four year old Americans had to enlist in a labor army. This labor army would provide the rest of Americans with all the basic goods and services needed and would eliminate the need to buy or sell using money. [9] While her theory seems impractical it was highly praised by first lady, Eleanor Roosevelt.

Prestonia and her husband moved to Winter Park in 1928. While in Winter Park she was interested in the civic and cultural affairs of the city. She contributed to the Animated Magazine edited by Hamilton Holt. One of her most famous contributions to the magazine was her 1944 entry titled “Grandma’s Declaration of Independence.” Prestonia gave lectures explaining her theory on poverty throughout Florida and New England. Prestonia was known in both Winter Park and New York City for advocacy to improve conditions for society’s less fortunate members.

Prestonia Mann Martin died on April, 1 1945. She was survived by three adopted children, Jonathan, Robin and Charmaine.

– Kerem K. Rivera

McDowall, John Witherspoon (1905-1969)

Coach, Professor, Athletic Director

John “Jack” Witherspoon McDowall, son of John W. M. and Sarah McDowall, originated in Newberry, Florida. McDowall received preparatory education first at Florida High School in Gainesville from 1922 to 1923 , then at the Rockingham, North Carolina High School until 1924. In high school, McDowall became heavily involved in sports, such as football, basketball, track, and baseball. He joined the All-Florida End and the All-Florida Guard, broke the record for the high jump, captained the baseball team, and won both football and basketball championships. In addition, he also joined the All-North Carolina High School End, broke the Southeastern Meet record of Florida for collages, and became the All-North America first basemen. In 1924, he attended the North Caroline State College, from which he received his Bachelor of Science degree in 1928. While at the college, he participated in football (freshman quarterback), basketball (captain in 1927 through 1928), baseball, track, played on the Pacific Coast All-Southern Team, and broke the state record for the high jump. Also in 1928, Who’s Who in American Sports included McDowall on its list. After graduation, he then became the coach for Asheville High School in North Carolina until 1928, his football team winning nine out of ten games; it might have made the championship but for an outbreak of influenza. At one point in the season, his basketball team won twenty games straight. McDowall joined organizations such as Blue Key, the Theta Kappa Nu fraternity, as well as receiving an honorary membership to the Golden Chain. In addition, he obtained a master’s degree in education from Duke University (Durham, North Carolina) in 1935.

John “Jack” Witherspoon McDowall, son of John W. M. and Sarah McDowall, originated in Newberry, Florida. McDowall received preparatory education first at Florida High School in Gainesville from 1922 to 1923 , then at the Rockingham, North Carolina High School until 1924. In high school, McDowall became heavily involved in sports, such as football, basketball, track, and baseball. He joined the All-Florida End and the All-Florida Guard, broke the record for the high jump, captained the baseball team, and won both football and basketball championships. In addition, he also joined the All-North Carolina High School End, broke the Southeastern Meet record of Florida for collages, and became the All-North America first basemen. In 1924, he attended the North Caroline State College, from which he received his Bachelor of Science degree in 1928. While at the college, he participated in football (freshman quarterback), basketball (captain in 1927 through 1928), baseball, track, played on the Pacific Coast All-Southern Team, and broke the state record for the high jump. Also in 1928, Who’s Who in American Sports included McDowall on its list. After graduation, he then became the coach for Asheville High School in North Carolina until 1928, his football team winning nine out of ten games; it might have made the championship but for an outbreak of influenza. At one point in the season, his basketball team won twenty games straight. McDowall joined organizations such as Blue Key, the Theta Kappa Nu fraternity, as well as receiving an honorary membership to the Golden Chain. In addition, he obtained a master’s degree in education from Duke University (Durham, North Carolina) in 1935.

McDowall joined the Rollins College faculty in 1929, where served as director of physical education and coach from 1929 to 1931, and as director of physical education and athletics for men from 1931 to 1939. In 1937, McDowall held the position of chairman of the division of physical education and athletics until 1939 , becoming in that year the professor of physical education for men (1939 to 1944, and again in 1949 to 1957). He also assumed role of chairman of the division of health and physical education from 1942 until 1943, director of physical education from 1944 to 1949, professor of psychology from 1944 to 1945, chairman of the division of health and physical education from 1943 to 1943, as well as that of director of athletics and chairman of the division of health and physical education (1949 to 1953). Although McDowall retired from active teaching at Rollins in 1956, he acted as a consultant to the athletic department until 1969. His attitude on coaching focused on character development through sports, thus precluding effortless victories. “I wouldn’t knowingly schedule a game with any team Rollins could lick 40-0… and I wouldn’t schedule a game with a team that could lick us 40-0, either. What the public wants to see and what is best for the players, too, is even contests.” [10] Owing to his distinctive contributions to the College, McDowall received the Rollins Decoration of Honor in 1942. In 1965, North Carolina added him to their Sports Hall of Fame.

McDowall joined the Rollins College faculty in 1929, where served as director of physical education and coach from 1929 to 1931, and as director of physical education and athletics for men from 1931 to 1939. In 1937, McDowall held the position of chairman of the division of physical education and athletics until 1939 , becoming in that year the professor of physical education for men (1939 to 1944, and again in 1949 to 1957). He also assumed role of chairman of the division of health and physical education from 1942 until 1943, director of physical education from 1944 to 1949, professor of psychology from 1944 to 1945, chairman of the division of health and physical education from 1943 to 1943, as well as that of director of athletics and chairman of the division of health and physical education (1949 to 1953). Although McDowall retired from active teaching at Rollins in 1956, he acted as a consultant to the athletic department until 1969. His attitude on coaching focused on character development through sports, thus precluding effortless victories. “I wouldn’t knowingly schedule a game with any team Rollins could lick 40-0… and I wouldn’t schedule a game with a team that could lick us 40-0, either. What the public wants to see and what is best for the players, too, is even contests.” [10] Owing to his distinctive contributions to the College, McDowall received the Rollins Decoration of Honor in 1942. In 1965, North Carolina added him to their Sports Hall of Fame.

McDowall, in addition to having an important role as coach and professor, also had memorable achievements within the greater Florida community. From 1943 to 1944, McDowall functioned as a United States Naval Lieutenant during World War II. In 1952, he successfully ran as a Democrat [11] for Orange County commissioner on a platform consisting of pro-business administration, better roads, country beautification, the Sports Fishermen’s Program, and conservation. Re-elected in 1956, McDowall held the position until 1960. McDowall died on May 25, 1969 from a heart condition. His wife, Sally McDowall, and a daughter, Sally F. Blake, survived him. McDowall received a memorial service at Knowles Chapel on the Rollins Campus.

– Angelica Garcia

McKean, Hugh F. (1908 – 1995)

Artist, Educator and Philanthropist

Throughout nearly three-quarters of the twentieth century, Hugh Ferguson McKean—10th President of Rollins College, artist, educator, museum director, collector, writer, philanthropist, and lover of nature— significantly shaped Rollins College and the City of Winter Park. Together with his wife Jeannette Genius McKean (1909–1989), McKean helped establish an enduring ethos and legacy of philanthropy, arts, and culture in Winter Park and beyond.

Throughout nearly three-quarters of the twentieth century, Hugh Ferguson McKean—10th President of Rollins College, artist, educator, museum director, collector, writer, philanthropist, and lover of nature— significantly shaped Rollins College and the City of Winter Park. Together with his wife Jeannette Genius McKean (1909–1989), McKean helped establish an enduring ethos and legacy of philanthropy, arts, and culture in Winter Park and beyond.

Hugh F. McKean, son of Mr. and Mrs. Arthur McKean, [12] was born in Beaver Falls, Pennsylvania, on July 28, 1908. He grew up in College Hill, Pennsylvania, moved to Central Florida with his family in 1920, and graduated from Orlando High School. [13] McKean earned his Bachelor of Arts degree from Rollins College in Winter Park, Florida, in 1930 and, in 1940, a Master of Arts degree from Williams College in Williamstown, Massachusetts. He studied art at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia, Art Students League in New York City, L’Ecole de Beaux-Arts in Fontainebleau, France, and Harvard University. McKean began teaching at Rollins College as a lecturer in Art in 1932 , eventually ascending the ranks in the Art Department. In 1945 he married Jeannette Morse Genius, granddaughter of Charles Hosmer Morse, the Chicago industrialist who, in the early part of the twentieth century, came to Florida and focused on restoring Winter Park’s economy, preserving the aesthetic beauty of the town, and developing its educational and cultural resources. Morse is remembered as the founder of the Winter Park Land Company, a Rollins College Trustee, and one of the greatest benefactors of the college in his day. [14]

It was in memory of her grandfather that Jeannette McKean built and donated The Morse Gallery of Art in 1942 on the Rollins campus. Hugh McKean became its director in 1945, a position he held until his death, just months short of the opening of The Charles Hosmer Morse Museum of American Art, the Morse museum’s relocated home on Park Avenue North in Winter Park. In 1951, McKean assumed the presidency of Rollins, an appointment he accepted because of his devotion to the College [15] and one he held until 1969, at which time he became Chairman of the Board of Trustees and, through 1973, Chancellor of the College. Hugh McKean’s creative leadership mid-century onward is perhaps best highlighted by understanding something about his lifelong endeavors as an artist and art collector, as a lover of nature and champion of ecology, and as a teacher-scholar with indefatigable faith in young people. These facets of his life and accomplishments in particular are integrally tied to McKean’s civic , educational, cultural, and philanthropic contributions.

Throughout his life McKean was a painter, often inspired by the landscapes and people of Central Florida. His early realistically stylized portraiture eventually gave way to more Impressionistic work and, finally, to his maturity as a painter with a strong personal vision. [16] During his lifetime McKean’s works were exhibited locally and nationally. Always active in art circles, he also served as trustee of the Ringling Museum of Art in Sarasota, Florida, and of the Louis Comfort Tiffany Foundation in New York.

A love of nature connected Hugh Mc Kean to Louis Comfort Tiffany and his achievements in painting, décor, and, most prominently, in glass works of art. In the early 1900s, Louis Comfort Tiffany (1848–1933), a practicing decorative artist, built Laurelton Hall, his dream home in Oyster Bay, New York. In an article in The Little Sentinel, December 18, 1981, Hugh McKean described the sprawling estate as a “three-dimensional work of art, fabricated of marble, wood, plaster, winds, glass, copper, rains, light, sound, sunlight, flower gardens, running water, terraces, woods, hills.” [17] More than a mere residence for Tiffany, Laurelton Hall became a place where invited aspiring artists could live and create artworks for periods of up to two months, enabled by a foundation Tiffany established to further help young artists. [18] In 1930, when Tiffany was 82, Hugh McKean visited Laurelton Hall as one such burgeoning art student. In a piece in the Sunday, April 15, 1979 Florida Magazine, McKean recalled that Tiffany “talked about the importance of beauty…. I thought he was wonderful.” He added, “Jeannette liked his work and I liked the man.” To the McKeans, Tiffany stood for a world of sensitivity and beauty [19]—values the couple apparently greatly admired and emulated.

A love of nature connected Hugh Mc Kean to Louis Comfort Tiffany and his achievements in painting, décor, and, most prominently, in glass works of art. In the early 1900s, Louis Comfort Tiffany (1848–1933), a practicing decorative artist, built Laurelton Hall, his dream home in Oyster Bay, New York. In an article in The Little Sentinel, December 18, 1981, Hugh McKean described the sprawling estate as a “three-dimensional work of art, fabricated of marble, wood, plaster, winds, glass, copper, rains, light, sound, sunlight, flower gardens, running water, terraces, woods, hills.” [17] More than a mere residence for Tiffany, Laurelton Hall became a place where invited aspiring artists could live and create artworks for periods of up to two months, enabled by a foundation Tiffany established to further help young artists. [18] In 1930, when Tiffany was 82, Hugh McKean visited Laurelton Hall as one such burgeoning art student. In a piece in the Sunday, April 15, 1979 Florida Magazine, McKean recalled that Tiffany “talked about the importance of beauty…. I thought he was wonderful.” He added, “Jeannette liked his work and I liked the man.” To the McKeans, Tiffany stood for a world of sensitivity and beauty [19]—values the couple apparently greatly admired and emulated.

In 1955, the McKeans presented the first contemporary exhibit of Tiffany’s art at the Morse Gallery of Art, yet by this time Tiffany’s Art Nouveau creations were considered so passé that the couple was able to pick up inexpensive examples of Tiffany’s work at antique shops in Manhattan. Then, in 1957, after Laurelton Hall was destroyed by fire, the McKeans were invited to the Long Island mansion by the artist’s daughter—who knew of Hugh’s long-time admiration and knowledge of her late father—to salvage what was left of the estate. The McKeans accepted at once and purchased, for a modest price, everything that was salvageable. [20] By the 1980s, Hugh and Jeannette had amassed a 4,000 piece-collection of 19th- and 20th-century glass, paintings, prints, pottery, and decorative arts valued conservatively in 1987 at $6 million. Their Tiffany collection, much of it housed at the Charles Hosmer Morse Museum of American Art, remains the most comprehensive collection of Tiffany’s work anywhere in the world.

Ensuring access to the collection was always a concern for the McKeans. Beginning in 1976, McKean became the President of the Charles Hosmer Morse Foundation, set up in the 1950s to fund the museum; the foundation controls the collection of Tiffany Art Glass and American paintings collected by the McKeans. And while Hugh McKean did not live to see the opening of the museum space on Park Avenue, he was integrally involved in its design and concept: “To enrich the cultural life of the community and thereby carry into the future the legacy Charles Hosmer Morse and his granddaughter Jeannette Genius McKean left to Winter Park.” [21]

As if by extension of the values of Morse, McKean carried into the future his own unique legacy. Following his retirement from the Rollins College Board of Trustees in 1975, McKean, still committed in the art world, began writing prolifically about Tiffany the man, his art, and his period. In 1980, Doubleday & Company, Inc., published McKean’s The “Lost” Treasures of Louis Comfort: Tiffany. Additional works by McKean about Tiffany followed, including: The Treasures of Tiffany: A Special Exhibition Presented by the Chicago Tribune at the Museum of Science and Industry in Chicago from the Collection of the Charles Hosmer Morse Foundation by Louis Comfort Tiffany (Designer), Hugh F. McKean (Author), published by the Chicago Review Press (1982); Louis Comfort Tiffany by Hugh F. McKean, published by Weingarten (1988); and, in 2001, Lost Treasures was republished by Schiffer Publishing. These works offer McKean’s reflections on various artistic works, such as Tiffany’s windows, paintings, decorative arts, and more. Mc Kean’s musings on the importance of art and beauty, The Lovely Riddle Reflections on Art, was published by The Morse Museum of American Art in 1997.

Hugh McKean was an early proponent for preserving the Florida’s natural beauty and advocating for the state’s sound planning. Together with his artistic and creative written expressions, Hugh McKean’s love of beauty was paralleled at his residence, Wind Song — a lakefront Mediterranean-style home set in a natural Florida oak hammock in Winter Park. Beginning with C. H. Morse’s land purchase on the shores of Lakes Mizell, Barry, and Virginia in 1920 and the construction of Wind Song in 1936 by Richard M. and Arthur E. Genius, Jeannette’s father and uncle, the environmental interests of Morse were continued throughout the adult lives of Hugh and Jeannette during their residence and stewardship of the flora and fauna at Wind Song from 1951 until their deaths in last decades of the 20th century. Wind Song remains preserved through The Elizabeth Morse Genius Foundation, named for Jeannette’s mother, which governs the McKeans’ real estate holdings.

The McKeans’ commitment to beauty, and bringing beauty to everyday life and, significantly, to Rollins, was often made tangible on the campus of Rollins— on its grounds and in its buildings and their furnishings, many selected by the McKeans themselves.

The McKeans’ commitment to beauty, and bringing beauty to everyday life and, significantly, to Rollins, was often made tangible on the campus of Rollins— on its grounds and in its buildings and their furnishings, many selected by the McKeans themselves.

The commitment for a beautiful and better community, however, was not all surface. During his presidency, Hugh Mc Kean tirelessly advocated for a “community of learning rather than a seat of mass education.” [22] He wrote several treatises on the freedoms of American education, education in responsibility, and about the importance of student citizenship and values. [23] In many ways, Mc Kean thus represented an era.

The commitment for a beautiful and better community, however, was not all surface. During his presidency, Hugh Mc Kean tirelessly advocated for a “community of learning rather than a seat of mass education.” [22] He wrote several treatises on the freedoms of American education, education in responsibility, and about the importance of student citizenship and values. [23] In many ways, Mc Kean thus represented an era.

Hugh McKean “sat in the president’s chair for 18 years, and could claim a balanced budget, an endowment that had more than quadrupled, an enrollment that had grown from 600 to 1,000, nine new major buildings, and significant changes in the educational complexion of the College.” [24] Described in turns by colleagues, students, friends, and business associates as soft-spoken, caring, humble, humorous, approachable, visionary, and dedicated to freedom in inquiry, Hugh Mc Kean was a l so a man of broad intellectual interests, an avid supporter of technology and education, a story-teller, a naturalist, an unorthodox educator, and an optimistic leader. On Saturday, May 6, 1995, Hugh McKean, the “spirited gray Fox of campus story and song,” [25] died of cancer. He is buried in Chicago beside his wife, Jeannette.

This essay is resulted from the Rhea Marsh and Dorothy Lockhart Smith Winter Park History Research Grant of 2008-09.

This essay is resulted from the Rhea Marsh and Dorothy Lockhart Smith Winter Park History Research Grant of 2008-09.

– Denise K. Cummings

McKean, Jeannette Morse Genius (1909-1989)

Artist, Businesswoman, Philanthropist

Contrary to Shakespeare’s thoughts on the importance of a name, it is often a subject for conjecture and animated discussion: that men and women are shaped by the names they bear and that living up to those names somehow molds and enhances their lives, In that likelihood, Jeannette Morse Genius McKean was a fortunate woman, a woman who extracted the finest essence from each portion of her name to draw a life in which she found satisfaction and in which those who knew and loved her can take justifiable pride. For herself, perhaps Jeannette serves best, a name in which gentle graciousness sounds, which carries a connotation of daintiness, of an old-world charm and the “sweet humility” noted in the 1957 Tomokan dedicated to this “devoted friend and benefactress of Rollins College.” And in Jeannette (two n’s and two t’s, but she would never be the one to remind you), there is the upward lilt of childlike wonder and delight which allowed her to be “the earliest riser to meet the circus train, pencil and pad in hand… to sketch the yellow giraffes as they fly by.”

Her middle name was Morse, a lifelong reminder to her and to others of the power and presence that was her maternal grandfather, Charles Hosmer Morse, Chicago businessman, first visited Winter Park in 1881 with his partner, Franklin Fairbanks. Each purchased a lot on Interlachen Drive on Lake Osceola, Morse returning in 1904 to build his permanent home. “A city planner ahead of his time,” he encouraged acquaintances to come and build, and believing, “bought almost all of the undeveloped property in Winter Park.” He believed, too, in “an educationally balanced city” and to that end lent his support to the young Rollins College. Eventually, Jeannette assumed the presidency of her grandfather’s Winter Park Land Co,. proving herself to be a “tireless worker,” a leader of downtown beautification in Winter Park, and a businesswoman of competence and good instincts. She founded and chaired the Charles Hosmer Morse Foundation, established in his honor, as a non-profit, educational and philanthropic organization to create a suitable memorial for its namesake and to fund the Morse Gallery of Art. A second foundation was named for his daughter and Jeannette’s mother, Elizabeth Morse Genius.

Jeannette was at one time the owner of several successful shops in Winter Park, including the Center Street Gallery. Opened in 1947 as showcase for the paintings of a group of local artists, it remains a favorite stop for shoppers on Park Avenue. Her business acumen was additionally recognized in her election to the board of directors of Sun Bank, N.A. of Winter Park and of The Association Home in New York. Her commitment to Winter Park was noted by a grateful Chamber of Commerce as tey named her Outstanding Citizen of the Year in 1987.

Jeannette Morse Genius was born on June 26, 1909 in Chicago Illinois to Dr. Richard M. and Elizabeth Morse Genius. The family moved later to New York, and Jeannette attended schools in Wellesley (MA) after which, with her mother’s encouragement, she embarked on the study of art in New York. In 1936, like Grandfather Morse, the Genuises returned to build and live in Winter Park. Their Spanish Florida home with its rolling lawn faced, across Lake Virginia, the College which Mrs. Genius — again following in her father’s pathway — came to love and support (Daughter Jeannette had been introduced to Rollins 7 years earlier when she came from Chicago to attend the College’s 10-week Winter School program). It is a tribute to both and perhaps a foreshadowing of the future that in that same year, at age 27, Jeannette was elected to her first 3-year trusteeship at Rollins. In 1942 she again accepted that beloved yoke for a 33-year tenure that ended with retirement in 1975. In 1959, Jeannette donated funds for the building of Elizabeth Morse Genius Hall, a dormitory simply and affectionately known to generations of Rollins students as “Elizabeth Hall.” Her magnificent gift of the Morse Gallery of Art (1942) provided an appropriate and impressive setting for the College’s growing permanent collection of fine paintings, sculptures, and decorative arts.

If there was a budding artist in young Jeannette, that artist blossomed in her years with Hugh Ferguson McKean. Friends for a number of years, they were married after Hugh’s return from World War II in 1945, and a partnership was forged which brought not only a personal joy in living, but a shared love of beauty that was to touch their home, their college, their community, and within one significant sector, the world rof art. Jeannette and Hugh McKean were, “the wonderful people who saved the Tiffany collection.” Drawing on that sense of beauty which they initially perceived in each other, they have lovingly gathered and preserved the largest collection of Louis Comfort Tiffany artworks in the world. It is unique, says Hugh, because it is “…Tiffany’s collection if his own work. There is nothing else like it anywhere.”

Jeannette’s first brush with Tiffany art was in her parents’ Chicago home. “This is where I first learned to love them and appreciate them, because I was fascinated with the colors and the iridescence of the gold pieces, the Favrile glass that was made with gold tones.” But it was through Hugh that she “learned to admire and appreciate Tiffany. He was an emotional and mental giant.” In 1957, Laurelton Hall, the mansion owned by Louis Comfort Tiffany, was destroyed by a fire, and Hugh and Jeannette rescued everything that had been spared by the flames—glass windows, furniture, the Columbian Exhibition Chapel, and other remnants of the artist’s personal collection. Their collection is housed in the Morse Museum of American Art on Winter Park’s Welbourne Avenue, and hosts visitors from all over the world who come to see the astounding variety of beautiful works of Louis Comfort Tiffany. Pottery, glass, jewelry, mosaics, leaded glass windows, textiles, sculptures, paintings, prints, artists’ tools, and fragments of windows partially destroyed in the Laurelton Hall fire have been augmented over the years by purchases in antique and secondhand stores.

Beauty is an essential part of life. “We sensed it in each other right away. It brought us together and holds us together.” — Hugh Ferguson McKean

Jeannette’s own art had flourished over the years, “reflecting her personality rather than the fashionable trends of the times.” Ranging “from non-representational, dealing with moods and ideas, to tender study of a single flower… (her work) always speaks of goodness of life.” She “did abstracts,” but it was her oils, watercolors, and pastels of “the beautiful things in life” that were exhibited in Wellesley, New York City, Sarasota, Tampa, and Palm Beach. Traveling shows through Europe and South America and U.S. museums and galleries included her works, and her art joined the permanent collections of art museums in Georgia, New Hampshire, and Florida and numerous private individuals. One-artist shows displayed Jeannette’s work in New York City, Maitland, Daytona, and Palm Beach. A member of prestigious art clubs and associations, she was honored by awards which included the cherished first Annual Award for the Arts bestowed by the Governor of Florida in 1973. Again, in 1989, she was honored with a Florida Arts Recognition Award. She was particularly pleased that her 1953 entry in the Butler Gallery of American Art (Youngstown, OH) won first prize, awarded by the famous artist, Edward Hopper.

Rollins recognized Jeannette’s artistic design capabilities in 1944 by naming her Director of Exhibitions at the Morse Gallery of Art, and in 1967, she became Design Coordinator for the college. She was a busy and respected member of the Association of Interior Designers and worked actively with the Florida Federation of the Arts, gathering and preparing for them her first retrospective show (1942-1966) at the DeBary Mansion in DeBary, Florida.

In 1982, as a capstone to their “quiet benefactions,” Jeannette and Hugh McKean contributed $10,000 as a prize to a member of the Rollins College faculty to support a “teaching-related project, a research project, or an artistic work which contributes to the educational mission of the College.” President Seymour has called the McKean Prize “a thoughtful and generous gesture…to permit a member of the Rollins faculty to enjoy a ‘once-in-a-lifetime’ opportunity to pursue a special academic interest or activity.” Since 1982, the McKean Prize has been granted annually, going to professors in every major division of the College curriculum. For her uncommon service to the College, Jeannette received the Rollins Decoration of Honor in 1943, and in 1954, the Algernon Sydney Sullivan Medallion. She was awarded the degree of Doctor of Fine Arts honoris causa in 1962, and in 1980, was presented, in appreciation, a gold pin with diamond at the annual Patrons’ Dinner.

“A dear friend, whose example of compassion, care, and gentle generosity touched us all and shaped the modern history of Rollins College. Her influence is felt everywhere on this campus, where she will always be remembered as the First Lady of Rollins College.” — President Thadeus Seymour

— Constance K. Riggs

This essay was originally published in the Oct. 1989 issue of Rollins Alumni Record (pp. 9-11).

Missildine, Ida May (1869-1963)

First Graduate of Rollins

On November 14, 1869, near Iberia, Missouri, Reverend Alfred H. and Anna Stuart Missildine gave birth to Ida May Missildine. Reverend Alfred’s occupation called for constant relocation, and by 1979, the family moved the Charleston, South Carolina, and soon after to Tryon, North Carolina. Just a few years later, in 1887, the family relocated again, this time to Winter Park, Florida.

On November 14, 1869, near Iberia, Missouri, Reverend Alfred H. and Anna Stuart Missildine gave birth to Ida May Missildine. Reverend Alfred’s occupation called for constant relocation, and by 1979, the family moved the Charleston, South Carolina, and soon after to Tryon, North Carolina. Just a few years later, in 1887, the family relocated again, this time to Winter Park, Florida.

During this time, Ida May had hopes of attending Wellesley Preparatory School, but because of her early interest in music, Rollins College in Winter Park, Florida seemed to be a better fit. She enrolled in the College in 1887, where she took voice and piano lessons. [26] In 1890, just three years later, she completed her studies, and along with Clara Guild, became one of two members of the first graduating class of Rollins College. Upon completion of her A.B. degree, Ida May remained at the College for another year, where she served as assistant teacher of piano. Following this, she studied for another year, from 1891-1892, at the New England Conservatory of Music in Boston, Massachusetts. She then taught music at Converse College in South Carolina for another two years, and later worked with private teachers in New York. In 1894, Missildine continued her education in Berlin, where she studied under the tutelage of Professor Klindworth.

At the turn of the century, Missildine made her home in Missouri, where she began to formally teach students how to play the organ. Just six years later, in 1916, she served as organist for the First Presbyterian Church in Kirkwood, Missouri. There she gained considerable repute as an organist, and forty years later, in 1957, retired with the title of “Organist Emeritus” and with a $100 a month pension for life. [27] That same year, she also received the Rollins Decoration of Honor, marking the sixty-seventh anniversary from the College. Just a few years before, on her fiftieth anniversary from the College, she received the honor scroll for the Rollins College Golden Circle. [28]

Rollins continued to request her presence at their reunions, but illness struck Missildine, confining her to her Edgewater home in Missouri. Soon after, due to a stroke, Missildine was transferred to Rock Hill Resting Home, a nursing facility about 15 minutes from her residence. On April 17, 1963, Ida May Missildine passed away. Family members gathered two days later to lay her body to rest in Oak Hill Cemetery, Kirkwood, Missouri. For those that knew her the best regarded her as the person who created, “harmonies of just those of music; they have also been harmonies emanating from the soul of an artist who have enriched the lives of her fellowmen.” [29]

– Alia Alli

Mizell, David Jr. (ca.1804-1884)

First white settler of Winter Park

David Mizell’s history is somewhat convoluted because one of Mizell’s ten children shared his name. Some sources refer to Mizell’s son as David Mizell Jr. Mizell was said to be a descendent of French Huguenots that arrived in the Colonies before the outbreak of the American Revolution. The family originally had the name Moselle, before changing it to the Anglicanized Mizell. The Mizell family’s legacy in America began with three brothers: Luke, William and David. After settling off the Eastern Coast of North Carolina the three brothers each moved their separate ways south. William’s lineage went to Georgia, Luke’s to Alabama, and David’s to Florida. [30]

David Mizell’s history is somewhat convoluted because one of Mizell’s ten children shared his name. Some sources refer to Mizell’s son as David Mizell Jr. Mizell was said to be a descendent of French Huguenots that arrived in the Colonies before the outbreak of the American Revolution. The family originally had the name Moselle, before changing it to the Anglicanized Mizell. The Mizell family’s legacy in America began with three brothers: Luke, William and David. After settling off the Eastern Coast of North Carolina the three brothers each moved their separate ways south. William’s lineage went to Georgia, Luke’s to Alabama, and David’s to Florida. [30]

Although Mizell was not the town founder, he and his family settled the area in 1858. [31] He was said to have been convinced to come down to Central Florida from Alachua County on a suggestion by his son John, who believed that the area held high prospects. [32] Taking a chance, Mizell purchased eight acres of land surrounded by lakes from Isaac W. Rutland. After traveling to his land on horseback his daughter took her sycamore riding whip and stuck it into the ground, marking the area where the Mizell family would build their first log cabin. [33] Mizell named the settlement Lake View as it was surrounded by lakes. These lakes are today known as Mizell, Berry, and Virginia. [34] The name of his settlement was later changed to Osceola in 1870 in honor of a famous Seminole warrior. [35] Whether the settlement was more commonly known as Lake View or Osceola makes little difference as the settlement would later become what is known today as the City of Winter Park.

After founding the settlement, Mizell experienced success growing cotton on his land. [36] The mild climate and abundant water allowed for him to make a profit growing cotton. With his success as a planter, Mizell became a prominent citizen of Orange County. His son John became a county judge, and his other Son, David, became the first sheriff of Orange County. Unfortunately, the younger David was ambushed and killed in the line of duty. The younger Mizell’s death sparked a feud between the Mizell Family and the Barber Family. [37]

After founding the settlement, Mizell experienced success growing cotton on his land. [36] The mild climate and abundant water allowed for him to make a profit growing cotton. With his success as a planter, Mizell became a prominent citizen of Orange County. His son John became a county judge, and his other Son, David, became the first sheriff of Orange County. Unfortunately, the younger David was ambushed and killed in the line of duty. The younger Mizell’s death sparked a feud between the Mizell Family and the Barber Family. [37]

The elder David Mizell became the first chairman of the Board of Orange County Commissioners and even had a hand in signing Florida’s Constitution of 1868. [38] In his later years, Mizell lived with one of his sons in Conway, an area located in East Orange County, Florida. His son died soon after and he bought the house from his son’s widow and lived in it until 1884. Mizell died on January 6, 1884 and was buried in Conway cemetery. [39]

– David Irvin

Moon, Bucklin Rensaalear (1911-1984)

Alumni, Literary Editor, and Renowned

Born on May 13, 1911 to a lumberman, Chester D. Moon, and his wife, Edith Bucklin Moon, Bucklin Rensslear originated in Eau Claire, Wisconsin. He had two sisters, Marjorie and Peggy, and eventually moved to Winter Park, Florida with his family. Moon received his early education from various preparatory schools, such as Snyder School in Captiva Island, Rivers School and Fressenden in Massachusetts. After his expulsion from Fressenden for a “childish transgression,” [40] he attended Shattuck Military Academy in Fairbault, Minnesota. Owing to his problematic nature, the Shattuck administration recommended that Moon attend an experimental college, such as Rollins College in Winter Park, Florida, upon his graduation.

Born on May 13, 1911 to a lumberman, Chester D. Moon, and his wife, Edith Bucklin Moon, Bucklin Rensslear originated in Eau Claire, Wisconsin. He had two sisters, Marjorie and Peggy, and eventually moved to Winter Park, Florida with his family. Moon received his early education from various preparatory schools, such as Snyder School in Captiva Island, Rivers School and Fressenden in Massachusetts. After his expulsion from Fressenden for a “childish transgression,” [40] he attended Shattuck Military Academy in Fairbault, Minnesota. Owing to his problematic nature, the Shattuck administration recommended that Moon attend an experimental college, such as Rollins College in Winter Park, Florida, upon his graduation.

Moon experienced a vibrant, liberal Rollins atmosphere. [41] During the time he attended the College, beginning in 1929, Hamilton Holt had begun enforcing a radical educational model, emphasizing student-centered conference plans rather than the traditional lecture format. Moon joined the local X-Club fraternity, the football team, and became the associate editor for the school publication, Flamingo. Socially, he became friends with Zora Neale Hurston and in 1936 married a fellow Rollins student, Elizabeth (Betty) Frederica Vogler, with whom he had a daughter named Deborah. He eventually had three other children: Bucklin Jr., Abigail Jordan, and Sarah Lucey. Moon graduated with an Artium Baccalaureates degree in history in 1934; he took five years to graduate because he withdrew as a sophomore for two terms in order to work on a stuttering problem.

After college, Moon worked from home for several years, where he wrote stories and reviews. Afterwards, he moved to New York to become a reader, and then an editor for Doubleday from 1941 until 1951. Moon also wrote or edited books considered significant to the black community, such as The Darker Brother (1943); A Primer for White Folks (1945), which made Moon the first white to publish an anthology of writings by and for an American black audience; The High Cost of Prejudice (1947), an economic analysis; and Without Magnolias (1949), which won the George Washington Carver Award for best book of the year written by, or concerning, blacks. He left Doubleday after ten years to serve as a fiction editor for Collier’s Magazine, but in 1951 the U.S. House Un-American Activities Committee accused Moon of joining the Communist Peace Offensive. [42] Moon denied any such affiliation. In addition, publications such as Commonweal criticized the accusations. Despite the various protestations regarding the charges, however, Collier’s fired Moon in 1953. The accusation proved to be an event that largely ended his writing career and, emotionally, affected him greatly. [43]

After college, Moon worked from home for several years, where he wrote stories and reviews. Afterwards, he moved to New York to become a reader, and then an editor for Doubleday from 1941 until 1951. Moon also wrote or edited books considered significant to the black community, such as The Darker Brother (1943); A Primer for White Folks (1945), which made Moon the first white to publish an anthology of writings by and for an American black audience; The High Cost of Prejudice (1947), an economic analysis; and Without Magnolias (1949), which won the George Washington Carver Award for best book of the year written by, or concerning, blacks. He left Doubleday after ten years to serve as a fiction editor for Collier’s Magazine, but in 1951 the U.S. House Un-American Activities Committee accused Moon of joining the Communist Peace Offensive. [42] Moon denied any such affiliation. In addition, publications such as Commonweal criticized the accusations. Despite the various protestations regarding the charges, however, Collier’s fired Moon in 1953. The accusation proved to be an event that largely ended his writing career and, emotionally, affected him greatly. [43]

Moon edited the Doubleday Anthology in 1962 and eventually returned to editing under Pocket Books’ new imprint, Trident Press. After his divorce he married Ann Curtis Brown and moved to Marco Island, Florida. Following her death he wed Cornell science graduate, Marion Heldt. He settled in Tavernier and died in Plantation Key on September 19, 1984 from an illness. He left behind a memorable legacy despite the personal tragedy caused by the charges of communism, owing to the achievement of creating unique, largely non-stereotypical literary portrayals of black families in America. [44]

– Angelica Garcia

For more information, see the Bucklin Moon Manuscript Collection in the Rollins College Archives.

Morse, Charles Hosmer (1833-1921)

Major contributor and Trustee of Rollins College

Charles Hosmer Morse was born on September 23, 1833 in St. Johnsbury, Vermont. In his early years he attended public school and the St. Johnsbury Academy. He left school to become an apprentice for E. & T. Fairbanks and Co., a manufacturing company that became famous for creating industrial scales. His hard work and talent quickly earned him a promotion and a transfer to New York City.

Charles Hosmer Morse was born on September 23, 1833 in St. Johnsbury, Vermont. In his early years he attended public school and the St. Johnsbury Academy. He left school to become an apprentice for E. & T. Fairbanks and Co., a manufacturing company that became famous for creating industrial scales. His hard work and talent quickly earned him a promotion and a transfer to New York City.

After working as a clerk in New York for two years, Morse transferred to Chicago to help establish the firm of Fairbanks and Greenleaf. In 1862, he became a partner in Fairbanks and Greenleaf. In 1864, Morse co-founded Fairbanks, Morse and Co. in Cincinnati, Ohio. He went on to establish branches in Cleveland, Pittsburgh and Louisville. In 1869, Greenleaf fell ill and Morse returned to Chicago to take over Fairbanks and Greenleaf. He remained in Chicago until 1871 when the Great Chicago Fire destroyed Fairbanks and Greenleaf. Subsequently, Morse devoted his time and energy to becoming a dominant force in Fairbanks, Morse, and Co. [45]

After working as a clerk in New York for two years, Morse transferred to Chicago to help establish the firm of Fairbanks and Greenleaf. In 1862, he became a partner in Fairbanks and Greenleaf. In 1864, Morse co-founded Fairbanks, Morse and Co. in Cincinnati, Ohio. He went on to establish branches in Cleveland, Pittsburgh and Louisville. In 1869, Greenleaf fell ill and Morse returned to Chicago to take over Fairbanks and Greenleaf. He remained in Chicago until 1871 when the Great Chicago Fire destroyed Fairbanks and Greenleaf. Subsequently, Morse devoted his time and energy to becoming a dominant force in Fairbanks, Morse, and Co. [45]

In 1883 Morse arrived in Winter Park with Franklin Fairbanks. Morse decided to invest in land and even built himself a home in the area. In 1904 Morse purchased the Francis Knowles estate. He established his home, the Osceola Lodge, and became the largest landowner in Winter Park. He continued his involvement in the city by taking the reigns of the Winter Park Land Company. [46] In 1905 Morse made Winter Park his permanent winter home. While in Winter Park, he enjoyed outdoor sports, such as tarpon fishing and spent much of his leisure time enjoying nature. [47] Nonetheless, Morse remained a concerned citizen. He actively participated in the Winter Park Congregational Church and donated $5,000 to buy property for the church on the corner of New England and Interlachen.

Rollins College considered Morse to be one of its most important early contributors. In 1885, Morse donated one hundred dollars to assist in the building of the Parsonage, the home for the first President of Rollins College. In 1905 he donated $6,500 to the Rollins College Endowment Fund and became a member of Rollins College Board of Trustees in 1909. In 1920, only a year before his death, he donated $100,000 to the Rollins College Endowment Fund. Morse remained a trustee until his death in 1921.

Rollins College considered Morse to be one of its most important early contributors. In 1885, Morse donated one hundred dollars to assist in the building of the Parsonage, the home for the first President of Rollins College. In 1905 he donated $6,500 to the Rollins College Endowment Fund and became a member of Rollins College Board of Trustees in 1909. In 1920, only a year before his death, he donated $100,000 to the Rollins College Endowment Fund. Morse remained a trustee until his death in 1921.

Morse’s memory lives on in landmarks and gifts throughout the community that serve to highlight his accomplishments. In 1925, Elizabeth Morse Genius, his daughter, donated chimes and an Echo organ to the Winter Park Congregational Church in her father’s name. In 1942 Jeannette Genius McKean, his granddaughter, gifted to Rollins College the Morse Gallery of Art. The Morse Gallery was expanded in 1978 to become the Cornell Fine Arts Museum. The Osceola Lodge has been used by the Winter Park Institute. The Morse Memorial Park, five acres of land along Interlachen Ave, further honors Morse’s legacy.

– David Irvin

- Sumner G. Rand, “Genial Genius of Genius Drive Approaches 90th Year,” Orlando Sentinel, May 9, 1954, 6D. John Martin file, 45G, Rollins College Archives. ↵

- “John Martin Timeline,” John Martin file, 45G, Rollins College Archives. ↵

- Rand, “Genial Genius of Genius Drive Approaches 90th Year,” 6D. ↵

- “Tribute to John Martin,” John Martin file, 45G, Rollins College Archives. ↵

- Prestonia Mann Martin file, 05E, Rollins College Archives. ↵

- Enid Mastrianni. “Prestonia Mann Martin and Summer Brook,” Prestonia Mann Martin file, 05E, Rollins College Archives. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Prestonia Mann Martin, “Over the hills to the Townsend Plan! It’s Dole, Says Poverty Panacea Author,” The Cleveland News, January 14, 1936. ↵

- Tomokan, (1933). ↵

- Orlando Evening Star, (May 26, 1969). ↵

- 8 January 1938 announcement of Jeannette Morse Genius’s engagement to Hugh Ferguson McKean. Winter Park Topics: A Weekly Review of Social and Cultural Activities During the Winter Park Resort Season (Winter Park, FL, 1938,), 7. Charles Hosmer Morse File, Rollins College Archives. ↵

- Carole Arthurs. “A Tribute to a Giant of a Man.” Winter Park—Maitland Observer. Vol. 17, No. 19. (May 11, 1995), 1. Also see Robert D. McFadden. “H.F. McKean, Tiffany Expert Who Led College, Dies at 86.” New York Times (Mon., May 8, 1995), Obituaries. ↵

- Jim Forsyth. “Morse Traditions Live on in Winter Park.” Orlando Sunday Sentinel-Star (Feb. 22, 1953), 16-C. Morse first came to Winter Park in 1883 and, in 1904, organized the Winter Park Land Company with Harold A. Ward. ↵

- Press Release. Rollins College, Winter Park, Florida, May 13, 1951. Hugh F. McKean File, Rollins College Archives. ↵

- “Hugh F. McKean.” The Official Website of the Charles Hosmer Morse Museum of American Art. http://www.morsemuseum.org/about/hugh_mckean.html. ↵

- Sharon Carrasco. “McKean Reflects Back 50 Years of Laurelton Hall.” The Little Sentinel (Fri., Dec. 18, 1981), 4. ↵

- Chris Schneider. “The Tiffany Legacy Lives On at the Morse Gallery of Art.” Center Stage Vol. 7, No. 5 (May 1985) ↵

- Chris Cobbs. “Shine on, Mr. Louis Comfort Tiffany.” Florida Magazine (Apr. 15, 1979), 11. ↵

- Ibid. Also: William Weaver. “Florida’s Feast of Tiffany.” The New York Times Magazine (May 12, 1996). ↵

- See the Official Website of the Charles Hosmer Morse Museum of American Art. http://www.morsemuseum.org/about/hugh_mckean.html. ↵

- Hugh F. McKean. “Letter of Acceptance.” Written to Winthrop Bancroft, Chairman, Board of Trustees, April 3, 1952. Hugh F. McKean File, Rollins College Archives. ↵

- Some examples: “The Freedoms of American Education” (Summer 1965); “‘If I am the President, I am Also a Graduate of this College’: A Memorandum to the Students on Education in Responsibility” (Spring 1966); and “…a community dedicated to learning” (Rollins Press, Inc., Spring 1968). Hugh F. McKean File, Rollins College Archives. ↵

- Lorrie Kyle Ramie. “Hugh Ferguson McKean ‘30 ‘72H: Gentleman & Scholar.” Hugh F. McKean File, Rollins College Archives. ↵

- Dr. Fred W. Hicks. “Citation for Hugh Ferguson McKean.” Remarks offered at Rollins College Commencement, May 28, 1972, on the occasion of McKean receiving the Honorary Degree Doctor of Fine Arts. Hugh F. McKean File, Rollins College Archives. ↵

- Grill Fontaine, “Missouri Visitor Sees Great Change In Rollins College Since the 1800s,” The Corner Cupboard, August 19, 1954, p. 11. ↵

- Rollins Alumni Record, “ 1890 ’s Graduate Visits Campus,” October 1954, Department of Archives and Special Collections, Box 150E, Olin Library, Rollins College, Winter Park, Florida. ↵

- “Decoration of Honor Conferred on Ida May Missildine,” Charter Day Convocation, April 28, 1957. ↵

- President McKean, “Ida May Missildile’s Sixty-Seventh Anniversary of Her Graduation,” April 28 , 1957, Department of Archives and Special Collections, 150E, Olin Library, Rollins College, Winter Park, Florida. ↵

- “History of Prominent Mizell Family Recorded.” Tampa Sunday Tribune, Sunday, August 16, 1953. ↵

- Winter Park Sun. January 25, 1958. 5. ↵

- Shepherd, Kathleen. “A Brief historical sketch of my Hometown” Rollins College Archives. ↵

- Lewton, Dr. Fredrick Lewis. “Some Early History of Winter Park and Rollins College.” ↵

- “History of Winter Park.” Winter Park Chamber of Commerce, 1966. ↵

- Andrews, Mark. “Despite Scalping, Fatal Ambush, Mizell Family Lead Orange in Early Days" Orlando Sentinel, December 27, 1992. ↵

- Shepherd, Kathleen. “A Brief historical sketch of my Hometown” Rollins College Archives. ↵

- Andrews, Mark. “Despite Scalping, Fatal Ambush, Mizell Family Lead Orange in Early Days" Orlando Sentinel, December 27, 1992. ↵

- Bacon, Eve. “Orange County’s First Pioneer Family Lies Buried in Orlando’s Newest Park.” Orlando Sentinel, Florida Magazine, January 19, 1969. ↵

- Blackman, William Fremont. History of Orange County Florida: Narrative and Biographical. E.O Painter Printing Co. Deland, Florida, 1927, p. 87. ↵

- Maurice O’Sullivan, “Total Eclipse,” (Rhea Marsh & Dorothy Lockhart Smith Winter Park History Research Grant Report 2002), 2. ↵

- Ibid., 6. ↵

- House of Representatives Committee on Un-American Activities, “Report on the Communist ‘Peace’ Offensive: A Campaign to Disarm and Defeat the United States,” April 1, 1959, Washington D.C., 108. ↵

- O’Sullivan, “Total Eclipse,” 10. ↵

- Ibid., 11. ↵

- “Charles Hosmer Morse.” July 8, 1959. Trustee File, 10B, Rollins College Archives. ↵

- Charles H. Morse. Winter Park Public Library. ↵

- W.F. Blackman. “Charles H. Morse.” History of Orange County Florida. Part II. p. 76-7. ↵