R

Rice, Charles Edward (1935-2008)

Alumnus, Board Chairman and Donor

Charles Edward Rice Jr. was born on August 4, 1935 in Chattanooga, Tennessee. He attended the University of Miami where he earned his Bachelors of Arts degree in 1958. He graduated from the South Louisiana State University’s School of Banking in 1963 and moved on to obtain his Masters in Business Administration from the Rollins College Crummer School of Business Administration in 1964. In 1975 Rice graduated from an advanced mana gement program at Har vard University.

Charles Edward Rice Jr. was born on August 4, 1935 in Chattanooga, Tennessee. He attended the University of Miami where he earned his Bachelors of Arts degree in 1958. He graduated from the South Louisiana State University’s School of Banking in 1963 and moved on to obtain his Masters in Business Administration from the Rollins College Crummer School of Business Administration in 1964. In 1975 Rice graduated from an advanced mana gement program at Har vard University.

After graduating from Rollins, Rice began working as a trainee at First National Bank of Orlando. [1] In 1965 he became the vice president of the First National Bank of Winter Park. Barnett Banks acquired the First National Bank of Winter Park in 1966. A year later Rice was appointed president of the Winter Park Bank. [2] In 1971 he was appointed executive vice president of Barnett Banks and fourteen months later became president. NationsBank (now Bank of America) acquired Barnett Banks in 1998 by which time Rice was chief executive officer and chairman of the bank. Rice led Barnett Banks for nearly three decades.[3]

Rice maintained his ties with Rollins even after beginning his career in the banking business. He met his wife, Diane Tauscher at Rollins. He had three children, and his daughter Michelle graduated from Rollins in 1991. Rice was an instructor of finance at the Crummer School of Business from 1965-1967. He was generous to both the Rollins and Winter Park communities. Rice served on the Board of Directors of the Winter Park Telephone Company, the Winter Park Memorial Hospital, the Loch Haven Art Center, and the Central Florida Council of the Navy League. In 1996 he was chair of a committee that aimed to raise $100 million for Winter Park schools.

Rice maintained his ties with Rollins even after beginning his career in the banking business. He met his wife, Diane Tauscher at Rollins. He had three children, and his daughter Michelle graduated from Rollins in 1991. Rice was an instructor of finance at the Crummer School of Business from 1965-1967. He was generous to both the Rollins and Winter Park communities. Rice served on the Board of Directors of the Winter Park Telephone Company, the Winter Park Memorial Hospital, the Loch Haven Art Center, and the Central Florida Council of the Navy League. In 1996 he was chair of a committee that aimed to raise $100 million for Winter Park schools.

Rice had served three terms as the chairman of the Rollins Board of Trustees. He was also a board member of the Rollins College Alumni Association and helped establish the Rollins Corporate Associates Program that obtained financial support for Rollins from the corporate community. He donated $1 million towards the Charles Rice Family Bookstore and the Diane Tauscher Rice Café, named after his wife. Rice also gave $250,000 to fund the President’s Dining Room in the Cornell Campus Center. He was inducted into the Rollins Alumni Hall of Fame in 1983 and received an honorary degree from Rollins on May 24, 1998.

Rice had served three terms as the chairman of the Rollins Board of Trustees. He was also a board member of the Rollins College Alumni Association and helped establish the Rollins Corporate Associates Program that obtained financial support for Rollins from the corporate community. He donated $1 million towards the Charles Rice Family Bookstore and the Diane Tauscher Rice Café, named after his wife. Rice also gave $250,000 to fund the President’s Dining Room in the Cornell Campus Center. He was inducted into the Rollins Alumni Hall of Fame in 1983 and received an honorary degree from Rollins on May 24, 1998.

Charles Edward Rice died on December 8, 2008 in his Boca Grande home.

– Kerem K. Rivera

Rice, John Andrew (1888-1968)

Controversial Professor, Founder of Black Mountain College

John Andrew Rice, born on February 1, 1888 to John Andrew and Anna Bell (Smith) Rice, originated in Lynchburg, South Carolina. His father had functioned as a college president (Colombia College in South Carolina), professor (Southern Methodist University in Dallas, Texas), and pastor. Rice attended the Webb School in Bell Buckle, Tennessee, where he received his pre-college preparatory education. From 1908 until 1911 he attended Tulane University in New Orleans, Louisiana, and received an Artium Baccalaureatus degree. Rice earned another A.B. (First Class in the Final Honour of School Jurisprudence) in 1914 from Oxford University, where he held the distinction of Rhodes Scholar, after which he conducted graduate work in the classics at the University of Chicago from 1916 through 1918. In 1914 he married Nell Aydelotte, with whom he had two children: Frank and Mary.

John Andrew Rice, born on February 1, 1888 to John Andrew and Anna Bell (Smith) Rice, originated in Lynchburg, South Carolina. His father had functioned as a college president (Colombia College in South Carolina), professor (Southern Methodist University in Dallas, Texas), and pastor. Rice attended the Webb School in Bell Buckle, Tennessee, where he received his pre-college preparatory education. From 1908 until 1911 he attended Tulane University in New Orleans, Louisiana, and received an Artium Baccalaureatus degree. Rice earned another A.B. (First Class in the Final Honour of School Jurisprudence) in 1914 from Oxford University, where he held the distinction of Rhodes Scholar, after which he conducted graduate work in the classics at the University of Chicago from 1916 through 1918. In 1914 he married Nell Aydelotte, with whom he had two children: Frank and Mary. He taught at the Webb School from 1914 until 1916. Additionally, Rice became a fellow for the University of Chica go in 1917 and fellow-elect in 1918, after which he worked in Washington, D. C. for the War Department, Military Intelligence Division, Department of Codes and Ciphers until 1919. The University of Nebraska appointed Rice as an associate professor of classics from 1919 to 1926, and then as the chairman of the department in 1926 until 1928. He taught classics at the New Jersey College for Women of Rutgers University beginning in 1927. Owing to a faculty controversy, however, Rice left Rutgers in 1930. Additionally, Rice served as a Guggenheim fellow for research in Europe (1929 to 1930), the chairman for the League for Progressive Democracy (1937), a member of the American Association of University Professors, American Association of Rhodes Scholars, and Sigma Alpha Epsilon, and as a recognized authority on the writings of Dean Swift. He also submitted a story to Harpers Magazine, published in two parts in 1938, entitled “Grandmother Smith’s Plantation,” which received some criticism regarding factual inaccuracies from a relative of one of the article’s characters. [4]

He taught at the Webb School from 1914 until 1916. Additionally, Rice became a fellow for the University of Chica go in 1917 and fellow-elect in 1918, after which he worked in Washington, D. C. for the War Department, Military Intelligence Division, Department of Codes and Ciphers until 1919. The University of Nebraska appointed Rice as an associate professor of classics from 1919 to 1926, and then as the chairman of the department in 1926 until 1928. He taught classics at the New Jersey College for Women of Rutgers University beginning in 1927. Owing to a faculty controversy, however, Rice left Rutgers in 1930. Additionally, Rice served as a Guggenheim fellow for research in Europe (1929 to 1930), the chairman for the League for Progressive Democracy (1937), a member of the American Association of University Professors, American Association of Rhodes Scholars, and Sigma Alpha Epsilon, and as a recognized authority on the writings of Dean Swift. He also submitted a story to Harpers Magazine, published in two parts in 1938, entitled “Grandmother Smith’s Plantation,” which received some criticism regarding factual inaccuracies from a relative of one of the article’s characters. [4]

Rice arrived at Rollins College in 1930 to assume a professorship in the classics department, as a tenured instructor of Greek and Latin. While teaching at Rollins, however, Rice received notoriety from the series of events eventually labeled the “Rice Affair.” A proponent of radical teaching methodologies, Rice elicited both strong negative and positive reactions from the faculty and students. John Tiedtke described him as “very bright and a highly entertaining conversationalist. He was able to present his points of view, even when he was wrong in a way that was very convincing” but remarked that he had the habit of “making controversial statements in order to disturb people.” [5] Whereas some students and at least eight professors respected Rice highly, some felt Rice was a “dangerous influence” [6] on the minds of impressionable college students. According to sworn affidavits against Rice, the maverick professor rarely taught Greek or Latin during his classes, instead holding discussions on “sex, religion, [and] unconventional living.” [7] Rice frequently made comments against school institutions, such as fraternities and the church, shocked young women with his socially unacceptable dress, and often demonstrated explicit hostility towards conventional opinions and those who held them. [8] Pressured into taking action against Rice, President Holt dismissed Rice after two years at Rollins. Despite the complaints against Rice, his release resulted in opposition from the faculty (some of whom resigned in protest), who criticized Holt’s casual removal of a tenured professor. The controversy prompted a review of college tenure policies by the American Association of Colleges. Rice, accompanied by several former Rollins professors and students, moved to Asheville, North Carolina and founded Black Mountain College in 1933. The college Rice founded closed after only twenty-seven years, but became renowned for providing innovative, experimental education. Additionally, Rice continued to publish short stories in magazines such as Collier’s Weekly and The New Yorker, also authoring several books: I Came Out of the Eighteenth Century (1942) and Local Color (1955).

frequently made comments against school institutions, such as fraternities and the church, shocked young women with his socially unacceptable dress, and often demonstrated explicit hostility towards conventional opinions and those who held them. [8] Pressured into taking action against Rice, President Holt dismissed Rice after two years at Rollins. Despite the complaints against Rice, his release resulted in opposition from the faculty (some of whom resigned in protest), who criticized Holt’s casual removal of a tenured professor. The controversy prompted a review of college tenure policies by the American Association of Colleges. Rice, accompanied by several former Rollins professors and students, moved to Asheville, North Carolina and founded Black Mountain College in 1933. The college Rice founded closed after only twenty-seven years, but became renowned for providing innovative, experimental education. Additionally, Rice continued to publish short stories in magazines such as Collier’s Weekly and The New Yorker, also authoring several books: I Came Out of the Eighteenth Century (1942) and Local Color (1955).

– Angelica Garcia

Richardson, Israel

African American Settler

Israel Richardson was born to two African Americans, James and Rachael Richardson, in Monticello, Florida around 1858. In 1870, by the age of twelve, he lived in Township 5, Jefferson County, Florida. The Richardson’s were a pioneer African American family in Winter Park, Florida. They moved to Winter Park in the 1880s. [9] In 1881, when Winter Park town founders Loring Chase and Chapman planned the layout for the town, they designated the west side, named Hannibal Square after the famous Carthaginian general, as the African American part of town. They separated small plots of land on the West side for African Americans. The plots were considerably smaller than those offered to the whites on the east side. Many African Americans bought land to grow citrus and domesticate animals. This opportunity to own land took place shortly after the end of Reconstruction saw the return of Democratic Party rule in the former states of the Confederacy.

The transition from slavery to freedmen was rife with political, social, and economic injustices. For example, many whites would take advantage of African American illiteracy by offering a verbal work contract that was different from the written contract they made the former slaves sign with an “x” mark. [10] Despite the injustices, Israel obtained land despite economic and social obstacles. He owned an orange grove near Pennsylvania Avenue in addition to residential property. Israel also raised animals and plants on his property. [11] His family occupied this property well into the twentieth century. Israel was involved with the Ward Chapel African Methodist Episcopal Church located on Pennsylvania Avenue. [12] Israel’s son, Israel Richardson Jr. ran his own barbershop on West Welborne Ave. [13]

The transition from slavery to freedmen was rife with political, social, and economic injustices. For example, many whites would take advantage of African American illiteracy by offering a verbal work contract that was different from the written contract they made the former slaves sign with an “x” mark. [10] Despite the injustices, Israel obtained land despite economic and social obstacles. He owned an orange grove near Pennsylvania Avenue in addition to residential property. Israel also raised animals and plants on his property. [11] His family occupied this property well into the twentieth century. Israel was involved with the Ward Chapel African Methodist Episcopal Church located on Pennsylvania Avenue. [12] Israel’s son, Israel Richardson Jr. ran his own barbershop on West Welborne Ave. [13]

– Kerem K. Rivera

Rittenhouse, Jessie Bell (1869-1948)

Poet, Editor and Donor

Jessie B. Rittenhouse was born in Mt. Morris, New York in 1869. She attended the Genesee Wesleyan Seminary in Lima, New York, and then taught English before pursuing a career in journalism. She reviewed books for various newspapers and press syndicates before accepting a position as a modern poetry lecturer at Columbia University in 1900, the very same year Rittenhouse edited a translation of The Rubiyat of Omar Khayyam. In 1905, Rittenhouse joined the editorial staff of the New York Times. She also joined the staff of the Bookman, a literary magazine, and held both positions until 1915.

During this time she corresponded with poets from all over the country. She began editing and publishing compilations by these poets. Her first compilation, The Younger American Poets, was in 1904. She continued to publish compilations until 1927 and befriended many of the most famous poets of the age, including T.S Elliot, Robert Frost, and Sara Teasdale. Rittenhouse also published her own poetry in four volumes: The Door of Dreams (1918), The Lifted Cup (1921), The Secret Bird (1930), and My House of Life (1934). Rittenhouse is mostly remembered for her anthologies rather than her own collections. She worked to promote poetry, when many critics believed its contemporary popularity had ended. In 1910, she was the only female founding member of the Poetry Society of America. She served as the secretary for the society for ten years, helping young poets realize their full potential. [14]

During this time she corresponded with poets from all over the country. She began editing and publishing compilations by these poets. Her first compilation, The Younger American Poets, was in 1904. She continued to publish compilations until 1927 and befriended many of the most famous poets of the age, including T.S Elliot, Robert Frost, and Sara Teasdale. Rittenhouse also published her own poetry in four volumes: The Door of Dreams (1918), The Lifted Cup (1921), The Secret Bird (1930), and My House of Life (1934). Rittenhouse is mostly remembered for her anthologies rather than her own collections. She worked to promote poetry, when many critics believed its contemporary popularity had ended. In 1910, she was the only female founding member of the Poetry Society of America. She served as the secretary for the society for ten years, helping young poets realize their full potential. [14]

In 1924 Rittenhouse married a fellow poet, Clinton Scollard and moved to Winter Park, Florida. While in Winter Park, she established the Poetry Society of Florida, made up of local poetry aficionados. She attempted to inspire youth interest in poetry by sponsoring contests for new poetry through the Poetry Society of Florida. Rittenhouse met Hamilton Holt through her work with the Poetry Society of Florida, and Holt convinced Rittenhouse to teach at Rollins College. In 1927, she began to instruct classes on poetry and acted as a poetry consultant for the College. For her valued service, she received an honorary degree of Doctor of Literature from Rollins College in 1928. Jessie Rittenhouse died on September 28, 1948 in Grosse Point, Michigan. Upon her death, Rittenhouse left over 1200 books of poetry and 1400 letters of literary correspondence to Rollins, which is housed in the College Archive.

– David Irvin

Robie, Virginia Huntington (1868-1957)

Writer and Artist

On October 18, 1868, Virginia Dare (Pendleton), wife of Reverend Thomas Sargent Robie, gave birth to Virginia Huntington in Salmon Falls , New Hampshire. Virginia Robie received her preparatory education in Boston, Massachusetts’ Newberry Seminary, various public and private schools, the School of Decorative Design at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, and the School of Decorative Design and Applied Ornament at the Art Institute in Chicago, Illinois. In 1903, Robie became the associate editor for the publication House Beautiful until 1913, when she became the department editor for Keith magazine. She served in this capacity until 1924. Robie also authored a substantial number of written works, often focusing on artistic topics, such as Historic Styles in Furniture (1904 and 1916), By-paths in Collecting (1912), Quest of the Quaint (1916 to 1927), Sketches of Manatee (1920), The New Architectural Development in Florida (1922), The Story of Coral Gavels (1923), A Century of Miniature Painting (1939), Baroque: A Second Blooming (1941), Looking Backward (1947), and the roughly biographical Pennyroyal (1953). In addition, Robie wrote fairytales, several children’s plays, dozens of book reviews, and contributed to publications such as Country Life, Century Magazine, International Studio, House and Garden, Ladies’ Home Journal, the World Book Encyclopedia, and Legion d’Honneur. She participated in many organizations, such as the Pen and Brush of New York, Chicago Woman’s Club, Orlando Art Association, Allied Arts , Shamrock League (as president) and, as an honorary member, Sorosis in Orlando. Her interests included American and Chinese porcelains, as well as medieval manuscripts.

On October 18, 1868, Virginia Dare (Pendleton), wife of Reverend Thomas Sargent Robie, gave birth to Virginia Huntington in Salmon Falls , New Hampshire. Virginia Robie received her preparatory education in Boston, Massachusetts’ Newberry Seminary, various public and private schools, the School of Decorative Design at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, and the School of Decorative Design and Applied Ornament at the Art Institute in Chicago, Illinois. In 1903, Robie became the associate editor for the publication House Beautiful until 1913, when she became the department editor for Keith magazine. She served in this capacity until 1924. Robie also authored a substantial number of written works, often focusing on artistic topics, such as Historic Styles in Furniture (1904 and 1916), By-paths in Collecting (1912), Quest of the Quaint (1916 to 1927), Sketches of Manatee (1920), The New Architectural Development in Florida (1922), The Story of Coral Gavels (1923), A Century of Miniature Painting (1939), Baroque: A Second Blooming (1941), Looking Backward (1947), and the roughly biographical Pennyroyal (1953). In addition, Robie wrote fairytales, several children’s plays, dozens of book reviews, and contributed to publications such as Country Life, Century Magazine, International Studio, House and Garden, Ladies’ Home Journal, the World Book Encyclopedia, and Legion d’Honneur. She participated in many organizations, such as the Pen and Brush of New York, Chicago Woman’s Club, Orlando Art Association, Allied Arts , Shamrock League (as president) and, as an honorary member, Sorosis in Orlando. Her interests included American and Chinese porcelains, as well as medieval manuscripts.

At Hamilton Holt’s request, Robie became associated with Rollins College in Winter Park, Florida, in 1928. She served as a special lecturer in the Winter School. From 1928 to 1929 (and then again in 1944), she taught art. Robie then became Rollins’ official interior decorator, while functioning as assistant professor of art (instructing in its history and appreciation) from 1932 until 1938. Utilizing her expertise in color and design, Robie furnished the female dormitories, such as Pugsley and Mayflower Halls (to the latter of she also contributed a piece of Plymouth Rock), promoting the development of the College’s Mediterranean style. Her skilled work earned her praise from the College and the Florida community. From 1938 until 1944, she served as the associate professor of art and, after she resigned, she received the title of professor emeritus of art, which she held until her death in 1957. She also held the title of chairman of the division of expressive arts from 1939 to 1940. Robie felt herself fortunate to have stayed at Rollins, owing to such reasons as the president’s ideals, the Florida climate, and the close relationship between the College and Winter Park. In turn, Robie received the Algernon Sydney Sullivan medallion on June 3, 1935 for her dedicated work on the Rollins campus. Her brother, Thomas Sargent Robie, with whom she lived during her retirement in Fort Myers Florida, survived her, and Rollins received a table, some china, a box of crosses, and several books from her estate.

At Hamilton Holt’s request, Robie became associated with Rollins College in Winter Park, Florida, in 1928. She served as a special lecturer in the Winter School. From 1928 to 1929 (and then again in 1944), she taught art. Robie then became Rollins’ official interior decorator, while functioning as assistant professor of art (instructing in its history and appreciation) from 1932 until 1938. Utilizing her expertise in color and design, Robie furnished the female dormitories, such as Pugsley and Mayflower Halls (to the latter of she also contributed a piece of Plymouth Rock), promoting the development of the College’s Mediterranean style. Her skilled work earned her praise from the College and the Florida community. From 1938 until 1944, she served as the associate professor of art and, after she resigned, she received the title of professor emeritus of art, which she held until her death in 1957. She also held the title of chairman of the division of expressive arts from 1939 to 1940. Robie felt herself fortunate to have stayed at Rollins, owing to such reasons as the president’s ideals, the Florida climate, and the close relationship between the College and Winter Park. In turn, Robie received the Algernon Sydney Sullivan medallion on June 3, 1935 for her dedicated work on the Rollins campus. Her brother, Thomas Sargent Robie, with whom she lived during her retirement in Fort Myers Florida, survived her, and Rollins received a table, some china, a box of crosses, and several books from her estate.

– Angelica Garcia

Rogers, Fred McFeely (1928-2003)

Our Favorite Neighbor

Article as it originally appeared in The Rollins Alumni Record (Summer 2003), 20-23.

“Farewell to Our Favorite Neighbor: In Honor of Fred Rogers ’51, March 20, 1928 – February 27, 2003”

Fred Rogers died as peacefully as he lived, a true American icon who embodied the spirit of peace and civility. Beginning in the tense early 1950s (when he developed his first television show, The Children’s Corner, in his native Pittsburgh), through the turbulent passions of the ’60s and ’70s, into the era of Hip Hop and the Internet, Fred Rogers and his Neighborhood were an oasis of calm and kindness for millions of American children and their parents. Few would complain about the television serving as a babysitter. Fred Rogers found his calling at the dawn of the Television Age. Indeed, after graduating from Rollins with a degree in music composition, he planned to enter the seminary and become a minister-until he saw his first children’s television show in his parent’s home in 1951. Disappointed with what he saw, Rogers had an epiphany- a brilliant recognition that he could accomplish his mission to help people in an entirely new way.

I’m a composer and piano player,” Rogers once told an interviewer, “a writer and television producer… almost by accident a performer… a husband, father, and grandfather. And I’m a minister. You know, most of us are many things, and I remember the marvelous feeling I had when I realized that many parts of who I am could be brought together in work for children and their families. That’s what I am the most: a man who cares deeply about children.”

He resolved to make television shows for children that were better than what he saw, and soon went to New York to work in the fledgling television industry. He started with NBC television as an assistant producer for The Voice of Firestone and later became floor director for The Lucky Strike Hit Parade, The Kate Smith Hour, and the NBC Opera Theatre. The medium of television was wide-open: experimental, part wasteland and part a medium for brilliant entertainment. Rogers is rarely mentioned in the company of that era’s great innovators- Sid Caesar, Jackie Gleason, Lucille Ball, Steve Allen, Ernie Kovacs- yet in his way he is part of that pantheon, for he changed children’s programming forever. Along with Kukla, Fran and Ollie (which ran from 1947 to 1957), Rogers paved the way for Sesame Street, the Muppets, Barney, and the entire world of children’s educational programming, yet Mister Rogers maintained its popularity right alongside them. At its commercial peak, in 1985-86, Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood drew 8 percent of American households to its friendly environs.

“When I first saw children’s television, I thought it was perfectly horrible,” Rogers once told Pittsburgh Magazine. “And I thought there was some way of using this fabulous medium to be of nurture to those who would watch and listen.” Much changed in American family life during the 33-year run of Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood, yet Rogers never changed the basic format of his show. (He did, however, add many characters, including several African-American and Latino characters.) The outside world changed greatly, but the Neighborhood remained timeless. The characters Mister McFeely (named for Rogers’ adored grandfather, with whom he spent much time as a child), Lady Elaine Fairchild, King Friday XVIII, Daniel Striped Tiger, X the Owl, and others-remained his lifelong co-stars and companions. He barely seemed to age in all those years. And his message of universal respect remained as meaningful in 2001, when the show aired its last episode, as it did when it began in 1968.

The program stood out for its cast of well realized characters, but above all for its quiet. Children were mesmerized by the tinkling of the trolley, the songs (Rogers composed more than 200 of them, including the show’s theme), the soft-spoken exchanges between Rogers and the other characters, and Rogers’ earnest discussions about things that children are concerned about. Most television shows and commercials are loud and call attention to themselves, but Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood was like hanging out in your living room with your mild mannered and loving uncle. Rogers’ signature move came at the beginning of each show, when he made himself comfortable by taking off his suit jacket and leather shoes and putting on his sweater and his sneakers, while singing, “Would you be mine, could you be mine, won’t you be my neighbor?” He subtly invited the viewer to be comfortable, and in fact Rogers said that he saw the show as an extension of his daily life, not a separate interlude.

In his three decades on the air with Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood, Rogers wore more than 24 cardigan sweaters. “My mother made a sweater a month for as many years as I knew her,” Rogers said. “And every Christmas she would give this extended family of ours a sweater. “She would say, ‘What kind do you all want next year?’ Then she’d say, ‘I know what kind you want, Freddy. You want the one with the zipper up the front.” Despite the show’s saccharine reputation, Rogers did not close his eyes to the rise of a divorce culture or avoid difficult topics on his shows. He brought a new emotional frankness to children’s programming. Children have heard-many of them for the first time–open and direct talk about divorce, conflict, adoption, religious faith, and death from the kindly, comforting Mister Rogers. During the Persian Gulf War, he made a series of public-service announcements telling parents how to talk to their children about war. No wonder the Village Voice once lauded him as the only authentic father figure on television. “I think children appreciate having a real person talk with them about feelings that are real to them. Why have two generations of children watched our programs? I’d say that’s why,” Rogers said.

In his three decades on the air with Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood, Rogers wore more than 24 cardigan sweaters. “My mother made a sweater a month for as many years as I knew her,” Rogers said. “And every Christmas she would give this extended family of ours a sweater. “She would say, ‘What kind do you all want next year?’ Then she’d say, ‘I know what kind you want, Freddy. You want the one with the zipper up the front.” Despite the show’s saccharine reputation, Rogers did not close his eyes to the rise of a divorce culture or avoid difficult topics on his shows. He brought a new emotional frankness to children’s programming. Children have heard-many of them for the first time–open and direct talk about divorce, conflict, adoption, religious faith, and death from the kindly, comforting Mister Rogers. During the Persian Gulf War, he made a series of public-service announcements telling parents how to talk to their children about war. No wonder the Village Voice once lauded him as the only authentic father figure on television. “I think children appreciate having a real person talk with them about feelings that are real to them. Why have two generations of children watched our programs? I’d say that’s why,” Rogers said.

Rogers was born on March 20, 1928, and grew up in Latrobe, Pennsylvania, an industrial city near Pittsburgh known for steel production, machine parts, tools, industrial ceramics, and Rolling Rock beer. He lived alone with doting parents until they adopted a daughter when he was 11, and he spent much of his time quietly, playing with puppets and making music. Even then, he and his family created an oasis of calm in a harsher environment. It is no wonder, then, that Rogers charmed the tough Rollins football players who sometimes would intimidate the Rollins music students. “He was a very likeable person, very gentle,” remembered Hap Clark ’49, one of the football players-many of whom, like Clark, were World War II veterans. “He had feelings for everybody, even the mean football players. The music students would cross the street to avoid us when we came down the street. Fred and I were joking about it last year, at our last Reunion together in March. I apologized. I said if I was ever mean to him, I was sorry. He laughed. He got a kick our of that.” Despite his “tough” image, Clark always attended Rogers’ piano recitals during their time at Rollins. Clark noted that all three of his children grew up watching his former classmate, and he joined them as an adult. “I watched the show, sure. It was so laid back. Fred had some wonderful ideas about trying to help people live a better life,” he said. Rogers actually spent a year at Dartmouth before transferring to Rollins, where he found a quiet, peaceful place to hone his music and intellect, while still finding time to have some fun. He studied music composition, and his studies in philosophy and religion inspired him to consider the ministry. He received the Canadian French Scholarship Award and participated in numerous organizations and activities, including Alpha Phi Lambda, Chapel Staff, After Chapel Club, French Club, Student Music Guild, Chapel Choir, Bach Choir, Welcoming Committee, Intramural swimming, and Pi Kappa Lambda.

At Rollins Rogers met his future bride, Sara Joanne Byrd Rogers ’50, a fellow music student who went on to become an accomplished concert pianist. They married in 1952 and had two children, James (born in 1959) and John (born in 1961), and they remained devoted to each other their entire lives. Joanne has been memorialized forever as Queen Sara in the Neighborhood of Make Believe. “Before he was anyone’s icon, he was my icon,” Joanne said. “I always have seen the wisdom and the quiet intelligence that’s there… It’s a kind of goodness and thoughtfulness that would have been quietly there but never known about if not for the media.” Mary Wismar-Davis ’76, ’80MBA related her feelings about an incident that took place during a Rollins Reunion alumni concert about a decade ago. “Fred was playing the piano for a large audience of alumni when Joanne, whose flight had been delayed, walked into the room. He immediately stopped playing, jumped up, excitedly ran over, gave her a big hug and kiss, and told her how happy he was to see her. It was such a beautifully spontaneous moment of affection and love between people who had been married many years, and it didn’t matter to Fred that the room was filled with people. That’s when I truly saw that the TV Fred Rogers and the real-life Fred Rogers were one and the same.”

At Rollins Rogers met his future bride, Sara Joanne Byrd Rogers ’50, a fellow music student who went on to become an accomplished concert pianist. They married in 1952 and had two children, James (born in 1959) and John (born in 1961), and they remained devoted to each other their entire lives. Joanne has been memorialized forever as Queen Sara in the Neighborhood of Make Believe. “Before he was anyone’s icon, he was my icon,” Joanne said. “I always have seen the wisdom and the quiet intelligence that’s there… It’s a kind of goodness and thoughtfulness that would have been quietly there but never known about if not for the media.” Mary Wismar-Davis ’76, ’80MBA related her feelings about an incident that took place during a Rollins Reunion alumni concert about a decade ago. “Fred was playing the piano for a large audience of alumni when Joanne, whose flight had been delayed, walked into the room. He immediately stopped playing, jumped up, excitedly ran over, gave her a big hug and kiss, and told her how happy he was to see her. It was such a beautifully spontaneous moment of affection and love between people who had been married many years, and it didn’t matter to Fred that the room was filled with people. That’s when I truly saw that the TV Fred Rogers and the real-life Fred Rogers were one and the same.”

After graduating from Rollins, Rogers did a two-year apprenticeship in New York, then returned to Pittsburgh to help develop The Children’s Corner for a new public television station, WQED-TV; the nation’s first community- sponsored educational television station. While developing this program, Rogers pursued his original goal and attended the Pittsburgh Theological Seminary. He was ordained a Presbyterian minister in 1963, the same year in which he moved briefly to Toronto to make his on-camera debut-a 15-minute program called Misterogers. In 1966, he returned to WQED and turned the show into the half-hour Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood. The show debuted nationally in 1968 (the same year as Laugh-In, the year of assassinations and riots) on the fledgling National Education Television (NET), which became the Public Broadcasting Service (PBS). The following year, it won two George Foster Peabody Awards for television excellence. The rest is history, as Rogers became one of America’s most recognized personalities and won a plethora of awards and recognitions, four Emmys among them. He has a star on Hollywood’s Walk of Fame, and on New Year’s Day in 2003, in his last public appearance, he joined Bill Cosby and Art Linkletter as co-Grand Marshal of the Tournament of Roses Parade. As Pittsburgh Magazine noted, it would take 25 pages to list all the awards Rogers has won, including the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2002, the nation’s highest civilian honor.

Rogers, of course, would be embarrassed to see such a list. A shy man who never thought of himself as a star or celebrity, his success was merely a means to the greater end of educating and nurturing. His family, his friends, the people he worked with, the people who knew and loved him, knew that the gentle, decent man who appeared on television every day was the real thing. “It takes a great deal of courage to be yourself,” said Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood associate producer Hedda Sharapan. “Fred Rogers would say, ‘All I can give is my honest self ‘ He was even willing to let the world see his vulnerabilities, to see when he couldn’t learn something quickly… He’s given us all more courage to be our honest selves and to appreciate our own humanness.” A former real-life neighbor of the Rogers, Jessica Reavis, made a telling point in her commemoration for Time, saying, “The most remarkable thing about Mister Rogers was nor that he loved children, although that was apparent to anyone who observed him even for a moment. It’s that he respected children, not just for their ability to amuse or inspire, but for their intellect, their inherent sense of right, and their penchant for honesty.” Rogers was open-hearted enough to love children unreservedly, but he went beyond that. He was humble enough to learn from them and grant them a respect rarely accorded by adults. Elsie Hillman, a trustee emeritus of WQED Multimedia, summed him up in this way. “Mister Rogers. What a gracious man he was. Never pretentious but always there. A teacher but never a lecturer, a man of wit and wisdom full of compassion and patience. How could anybody be so perfect? He would not want us to believe that he was perfect. He wanted to be one of us and for us to like him just that way, not to revere him. Fred Rogers made us feel good about ourselves because he seemed to understand us and to really love us. It was not a pretend, ‘in your face’ kind of love, but an in-your-heart kind of love.”

That legacy of unconditional love that is so hard for most people to give is Fred Rogers’ parting gift to his intimates, the Rollins community, and the millions of people who ever tuned in their television to listen to this unusual and remarkable man. He found his passions early in life and was able to translate them not only into a successful career, but to communicate them creatively in ways that affected the lives of people allover the world. In the midst of the Cold War, in 1987, Rogers took the extraordinary step of appearing on Russia’s longest-running children’s television program, and later welcomed that program’s host into the Neighborhood.

That legacy of unconditional love that is so hard for most people to give is Fred Rogers’ parting gift to his intimates, the Rollins community, and the millions of people who ever tuned in their television to listen to this unusual and remarkable man. He found his passions early in life and was able to translate them not only into a successful career, but to communicate them creatively in ways that affected the lives of people allover the world. In the midst of the Cold War, in 1987, Rogers took the extraordinary step of appearing on Russia’s longest-running children’s television program, and later welcomed that program’s host into the Neighborhood.

As a Rollins student, he was inspired by the phrase “Life is for Service” that is engraved in marble and mounted on the wall of the loggia near Strong Hall. He wrote it down on a small piece of paper and carried it in his wallet throughout his life as a reminder (in later years, a framed photo of the plaque given to him by Rollins music department director John Sinclair sat on his desk). Rogers gave his life to that homily. So many of us are better for it. “I received a package in March from Fred’s production company,” Sinclair related. “I had once shown Fred my cufflink collection, and he particularly admired one pair, so last May I gave this pair to him at his 50th wedding anniversary party in Pittsburgh. In the package I received, sent to ‘Cufflink Collector Extraordinaire,’ were the cufflinks I had given him, and written in Fred’s distinctive handwriting were the words ‘Thanks for letting me borrow these for a while.’ “Not only is it typical of the man that he would think of others during his final illness, but what a beautiful attitude. If only everyone thought of their time on earth as ‘borrowing it for a little while.'”

– Bobby Davis

“Frankly, I think that after we die, we have this wide understanding of what’s real. And we’ll probably say, ‘Ah, so that’s what it was all about.'”-Fred Rogers ’51

Rogers II, James Gamble (1901-1990)

Notable Architect

James Gamble Rogers II was born in Chicago, Illinois on January 24, 1901 to John A. and Elizabeth (Baird) Rogers. He spent the early part of his life in Wilmette and Winnetka, Illinois. After John A. Rogers suffered a massive heart attack, doctors told him that if he stayed in Chicago, he could expect to live an additional six months as opposed to two years if he moved to Florida. [15] The Rogers family moved to Daytona Beach, Florida when James was 15. James attended Daytona Beach High School and graduated in 1918. Soon thereafter, he was employed by the old Merchants Bank in Daytona. In 1921 he attended Dartmouth College in New Hampshire. While at Dartmouth he waited on tables to put himself through college. Although Rogers wanted to pursue a degree in architecture, Dartmouth did not offer an architectural degree, instead, the college only offered architectural courses. Nonetheless, he excelled in art courses and in the Thayer School of Civil Engineering. [16] He was also an accomplished swimmer in college.

In 1924, towards the end of his junior year, Rogers returned to Daytona Beach after his father suffered a heart attack. James joined his father’s architectural firm. In 1928 he opened his own branch office in Winter Park, Florida. When John A. Rogers died in 1934, James completed any ongoing projects his father left behind and focused of his new firm, Rogers, Lovelock and Fritz, established in 1935. Rogers developed a style that “emphasized the purity of early domestic architecture in America and the Western European countries,” [17] and avoided “exaggerated detail and meaningless exterior decoration.” [18] Rogers was called to work with the U.S. Corps of Engineers as head of the Architectural Section of their district office in Wilmington, North Carolina when WWII broke out. He later went to Pensacola and began working with an architectural firm.

Rogers worked on state buildings, institutions of higher learning and residential homes but retained his interest in Spanish, French, Provincial and American Colonial architecture while many twentieth century architects dwelled in Modernism, Expressionism and Constructivism. His work in Winter Park set the tone for much of the architecture throughout the community. He built a number of residences, one of the most famous being the Barbour residence located on North Interlachen Ave. The opulent residence was constructed with a “typical Andalusian cortijo” in mind. [19] The Spanish style house featured imported materials and furnishings from Spain, which was later turned into Casa Feliz Home Museum.

Rogers worked on state buildings, institutions of higher learning and residential homes but retained his interest in Spanish, French, Provincial and American Colonial architecture while many twentieth century architects dwelled in Modernism, Expressionism and Constructivism. His work in Winter Park set the tone for much of the architecture throughout the community. He built a number of residences, one of the most famous being the Barbour residence located on North Interlachen Ave. The opulent residence was constructed with a “typical Andalusian cortijo” in mind. [19] The Spanish style house featured imported materials and furnishings from Spain, which was later turned into Casa Feliz Home Museum.

Rogers also constructed Winter Park High School, Bush Auditorium at Rollins College, along with the Mills Library, Skillman Dining Hall, Crummer Hall and several dormitories at the college. He is most remembered for the construction of the Olin Library. The $4.7 million necessary to fund the building came from New York City’s Franklin W. Olin Foundation. Roger’s design for the library was both artistic and practical. The building features Romanesque elements and protective elements such as minimal windows to prevent sun damages to books. Spanish design elements are not incorporated into the interior in order to create more space.

Rogers also constructed Winter Park High School, Bush Auditorium at Rollins College, along with the Mills Library, Skillman Dining Hall, Crummer Hall and several dormitories at the college. He is most remembered for the construction of the Olin Library. The $4.7 million necessary to fund the building came from New York City’s Franklin W. Olin Foundation. Roger’s design for the library was both artistic and practical. The building features Romanesque elements and protective elements such as minimal windows to prevent sun damages to books. Spanish design elements are not incorporated into the interior in order to create more space.

Rogers died in 1990. He earned numerous awards including the Hamilton Holt Medal and honorary degree in 1985 from Rollins College and Architect of the Year from the Building Stone Institute in 1963. Many of his buildings and homes have withstood the test of time and stand strong.

– Kerem K. Rivera

Rollins, Alonzo W. (1832-1887)

Industrialist and College Benefactor

Born on March 20, 1832 at Lebanon Center, Maine, Alonzo W. Rollins became the second of eight children to Richard and Betsy Rollins, and of direct descent from James Rawlins, who migrated to America in 1632 and settled near Dover, New Hampshire on a farm still owned by members of the Rollins family. By the age of fifteen, Rollins had listened to countless prayers and heard continual discussions about the value of a Christian education. Keeping these morals in mind, Rollins departed from his native home at the age of 22. He eventually settled in Fort Dodge, Iowa, where he became engaged in the manufacture of brick and later, a paper composition called “straw board.” In December 1865, after the failure of both ventures, Rollins married Susan A. Bowman of Royalton, Vermont. Soon after their marriage, the couple relocated to Chicago, where Alonzo and his brother, H.M. Rollins, became very successful merchants selling dyes and supplies used in the manufacture of wool products. Here Rollins developed a liking for fine wool, and soon after became a wool expert.

Over time, Rollins became a respected businessman and an important leader in America’s rising textile industry. During the initial years of his success, Rollins purchased a home at 32 Aldine Square, a section of the city where, “women dressed very elegantly and were as vain as peacocks.” [20] From 1879-84, he served as trustee of the Sixth Presbyterian Church, which later merged with the First Presbyterian Church of Chicago. In subsequent years, his health began to fail, forcing Rollins to seek annual relief in Florida.

Over time, Rollins became a respected businessman and an important leader in America’s rising textile industry. During the initial years of his success, Rollins purchased a home at 32 Aldine Square, a section of the city where, “women dressed very elegantly and were as vain as peacocks.” [20] From 1879-84, he served as trustee of the Sixth Presbyterian Church, which later merged with the First Presbyterian Church of Chicago. In subsequent years, his health began to fail, forcing Rollins to seek annual relief in Florida.

In 1883 , during one of his annual pilgrimages, his wife’s good cooking sparked the kinship between Judge Lawrence and the Rollins family. Lawrence introduced the couple to the quaint city of Winter Park and to the property in which Alonzo and his wife would eventually purchase for $10,000. Upon arrival to this new city, Rollins continued to maintain close ties between his brothers, but nevertheless lamented that he had no sons or daughters to educate. Although he lacked a college education, Rollins maintained committed to high ideals and supported the value of a higher education. Out of his dedication to such principles, he believed the money did not belong to him. As a man of strong religious faith, he began to grow uneasy with his wealth and soon became determined to offer it to a notable cause. Because of this, he familiarized himself with the efforts of Lucy Cross and Fredrick Lyman.

On January 29, 1885, the General Congregational Church Association of Florida proposed the idea to found a Christian institution of higher education in the locations of Daytona Beach, Mt. Dora, Orange City, or Winter Park. Rollins seized the chance to make a leadership donation of $50,000 to the cause, swaying the choice of the campus site to Winter Park. With the organization of the College, April 28, 1885, Rollins College made him trustee and treasurer. He attended two annual meetings of the Board of Trustees before the decline of his health became evident. Alonzo Rollins passed away on September 2, 1887 at the premature age of fifty-six from a reoccurring ailment, gastro enteritis, and was later buried in the mausoleum at Mount Hope Cemetery, Chicago. He left his fortune to his widow, which at her death, bequeathed to the College a total of $222,475.

Even after his death, the legacy that Mr. Rollins created for himself continues to live on. According to the Winter Park Company, they, “recognize and honor him as one of the friends and leading benefactors of Winter Park and Florida…. His name is deservedly associated with all that Winter Park shall become and with the best interests of this Southern portion of our country.” [21]

– Alia Alli

Root, Eva Josephine (1853-1913)

Early Faculty Member

Born in 1853, Eva Josephine Root was the daughter of Dr. Simeon Pliny Root, a physician and surgeon, and his wife, Susan. Eva was born in Liberty, Michigan, and attended Hillsdale College, where her main studies were in English and French. She earned B.S. and M.S. degrees at Hillsdale and went on to serve in a number of academic positions, including High School Principal in Lexington, Illinois, and Principal of the Academy at the Sherman Female Institute (Sherman, Texas).

Miss Root came to Rollins in 1887 as Principal of the Sub-Preparatory Department and joined the faculty two years later, teaching natural science, French, and history. She lived for a time in Cloverleaf Cottage, a women’s residence hall, and also served as a housemother in Pinehurst Cottage, which was then home to male students.

Miss Root left Rollins in 1897, moving back to her home state of Michigan. She later taught at Mary Nash College, until health concerns led her to move back to Hillsdale, where she taught English and French on a part-time basis until her death in 1913.

In 1931, Miss Root’s sister, Mrs. William F. Van Buskirk, shared these highlights of Prof. Root’s years at Rollins:

Miss Root reveled in the study of the flora and fauna of Florida. Her nature-study classes were to her a source of great delight. Daytime or evening she was ready for a botanizing trip or a moth-netting excursion, the latter, especially enjoyed by the students were rather frequent. She had many an interesting tale to tell of these trips. She told one story which lost nothing in the telling and if she had not been a person with an established reputation for veracity, her hearers would certainly have raised a question. One day in poling through Maitland Run the boat met a school of bass “head on”, six of the fish jumped into the boat and one jumped out.

The Rollins students were quite given to serenading, they never failed to remember Miss Root who enjoyed these musical demonstrations to repletion . . .

She chose her never abundant wardrobe with great care and was usually becomingly attired. She was certain the instructor’s dress and appearance had a decided effect on the mind of the instructed.

When the first pavement was laid between Winter Park and Orlando, she purchased a bicycle and was happy in the exercise and freedom that riding the wheel afforded. At that time, roads in Florida were in such a primitive condition that riding either on horseback or in vehicle was not an unmixed pleasure but partook of the nature of hard work. To have a real road even so limited in extent was a matter for rejoicing.

Remembering Miss Root, a former Rollins student wrote, “I do wish to say how dear Eva Root was and what a power in Rollins College in its younger days.” Another remembered, “I think her outstanding achievement and glory was her ability to inspire ambition in young people with whom she came in contact. . . I know she was the greatest influence for good that ever came into my life.”

Ross, John Stoner (1925-2003)

Physics Professor and Master of the Science Program

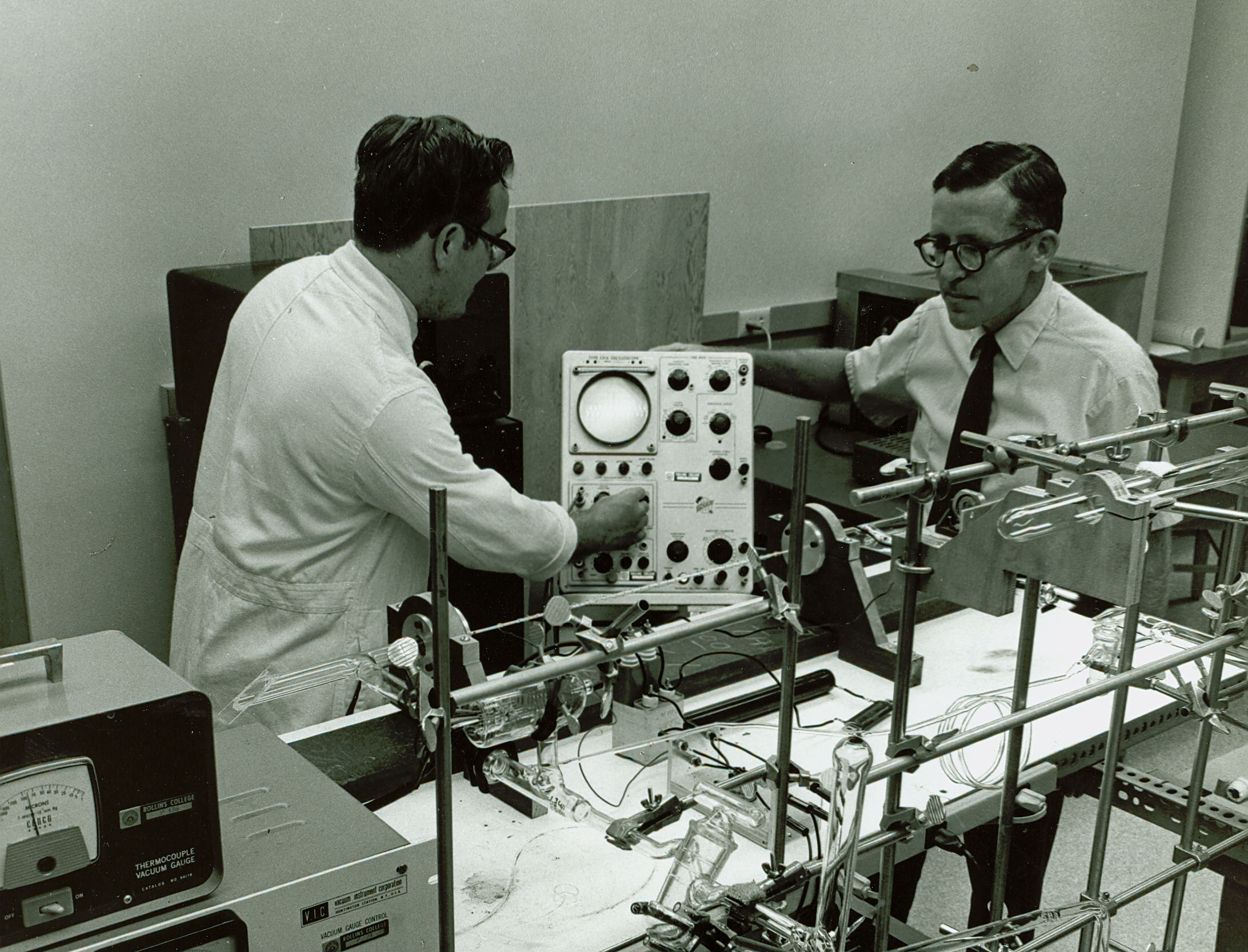

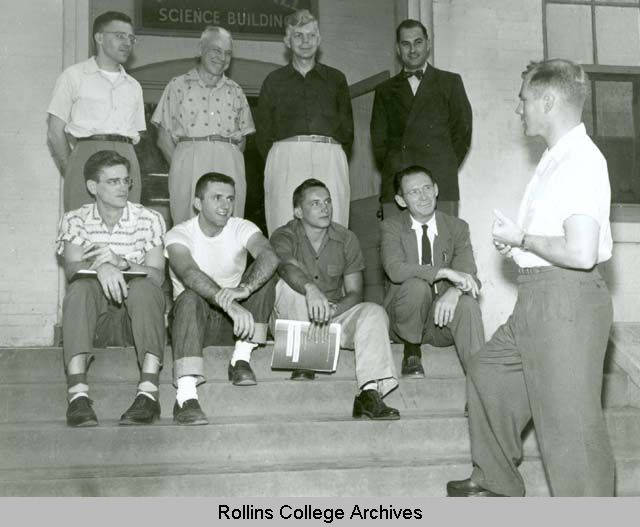

John Stoner Ross, born on September 28, 1925, originated in Ames, Iowa. He received preparatory education from Greencastle High School in Indiana, after which he enrolled in DePauw University where he received his Bachelor of Arts degree in 1947. Ross then conducted graduate studies at the University of Wisconsin, receiving his Masters of Science in 1948 and his Doctorate in 1952. His fields of study included physics, mathematics, and astronomy, with dissertation research pertaining to atomic optical spectroscopy. In 1948, Ross married Ann Cox, with whom he had eight children: Catharine (born 1951), David (born 1952), Martin (born 1954), Barbara (born 1956), Gregory (born 1962), Stephen, Kevin, and Eric. Even before completing his graduate studies, Ross found employment as a graduate assistant and a research physicist at the ANSCO Photographic Research Laboratory in Binghampton, New York. Ross also served as a consultant for the Radio Corporation of America (R.C.A.) Optics Engineering Group at an Air Force Missile Test Range, and at the Research Division of Radiation Incorporated.

In 1953, Hugh McKean invited Ross to teach at Rollins College in Winter Park, Florida. His teaching fields included astronomy, general physics, introduction to computers, quantum physics, and advanced laboratory. His research interests included high-resolution atomic spectromoscopy and self-paced course development for science majors. Ross participated in the 1975 summer Post-Keller College Workshop at Michigan State University for the preparation of instructional models for a physics course based on calculus. The Rollins College Research Fund provided some of the grants he needed to conduct his studies. In 1963 he became the Director Master of Science Program. Ross also served as head of physics department from 1965 until his retirement in 1993. To honor him for his service to the College, students celebrated his career with a party, and Rollins later named a classroom in the Bush Science Center after him. Students and faculty described him as having a shy, but contentious personality; his wife termed him a traditional Catholic.

In addition to teaching, Ross also published numerous papers and presented extensively. He wrote ten industrial and government reports and twelve articles on topics such as hyperfine structure and atomic isotope shifts in The Physical Review and the Journal of the Optical Society of America. His work won him various awards and honors, such as the Arthur Vining Davis Fellowship (1972), Archibald Granville Bush Professor of Science (1977 through 1980) and, along with Professor Edward Cohen, the first McKean Grant to support research in Oxford on Edmond Halley (1983). He also joined several academic and community organizations. He held memberships to the Optical Society of America, Southeastern Section of the American Physical Society, American Association of Physics Teachers, Federation of American Scientists, American Association for the Advancement of Science, Florida Academy of Sciences (as treasurer), American Association of University Professors, President of Central Florida Community Orchestra, Phi Beta Kappa, Sigma Nu, Omicron Delta Kappa. He even coached the Winter Park Soccer Club and received a position from the Boy Scouts of America Wekiwa District designating him as the chairman of the Eagle Board of Review. Ross died in 2003 at age seventy-seven from heart complications.

– Angelica Garcia

Russell, Annie (1864-1936)

Actress and Theater Legend

On January 12 , 1864 in Liverpool, England, Irish civil engineer Joseph Russell and his wife, Jane Mount Russell, welcomed their daughter, Annie, the first of their three children. Annie passed her early years in a convent in Dublin until 1869, when she and her family moved to Canada. According to Miss Russell, her father passed away sometime after their relocation, causing the family to suffer from destitution. Because of this, Annie’s mother decided to put her daughter on the professional stage to help maintain her family’s well-being.

In 1875 while on a tour of the United States and Canada, Rose Eytinge, a national and international star, came to Montreal in search of a young female to play a role in her play Miss Multon at the Montreal Academy of Music. Annie Russell, the only applicant for the role, impressed Eytinge [22] although not immediately because he proclaimed Russell was too young [23] and the rest of the world with her natural acting ability, and soon after, Haverly Juvenile Production granted her another role in the of H.M.S. Pinafore. According to Gary R. Plank, an authority on Annie Russell, she began a tour of the West Indies and South America in 1880 with the E.A. McDowell Acting Company, and after seven months, returned to New York, where in the fall of 1881, she appeared at the Madison Square Theatre in the play, Esmeralda. In years following, her popularity blossomed and she appeared in several other plays, including Our Society, Sealed Instructions, Captain Swift,  Broken Hearts, and Elaine. In 1884 Annie Russell tied the knot with Eugene W. Presbrey, however the marriage ended in divorce in 1897. During this period both physical and emotional stress afflicted Russell, forcing her to withdraw from the theatre. After four years of absence from the stage, she reappeared playing the lead female role in the play, The New Woman. During 1894-98, she preformed in a number of other plays, including Mice and Men, and Charles Frohman’s productions of Sue and Dangerfield, ’95, the latter led to her London debut in 1898. In the next decade, while spending most of her time in the United States, she returned to London to perform on three additional occasions: in 1899 she was to act in Catherine but had to return home due to illness; in 1905 when she acted in Major Barbara; and in 1913 when she acted in The Rivals and She Stoops to Conquer. In addition to spending summers at her house on the Maine Coast, she also began to share her time with English actor Oswald Yorke, later marrying him on March 27, 1904. the couple remained in New York, where Russell took the role of Puck in a presentation of Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

Broken Hearts, and Elaine. In 1884 Annie Russell tied the knot with Eugene W. Presbrey, however the marriage ended in divorce in 1897. During this period both physical and emotional stress afflicted Russell, forcing her to withdraw from the theatre. After four years of absence from the stage, she reappeared playing the lead female role in the play, The New Woman. During 1894-98, she preformed in a number of other plays, including Mice and Men, and Charles Frohman’s productions of Sue and Dangerfield, ’95, the latter led to her London debut in 1898. In the next decade, while spending most of her time in the United States, she returned to London to perform on three additional occasions: in 1899 she was to act in Catherine but had to return home due to illness; in 1905 when she acted in Major Barbara; and in 1913 when she acted in The Rivals and She Stoops to Conquer. In addition to spending summers at her house on the Maine Coast, she also began to share her time with English actor Oswald Yorke, later marrying him on March 27, 1904. the couple remained in New York, where Russell took the role of Puck in a presentation of Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

Concluding her engagement with the play, Russell continued to perform, produce and direct in the professional theatre until she became afflicted with Influenza, forcing the actress to leave the stage into an early retirement in January 1918. By 1923, Russell sold her New Jersey home, moving to St. Petersburg, Florida, and then later to Winter Park, where she began to feel homesick. One of her close friends, Mary Louise Bok, took notice to Russell and her fascination with the Rollins College Theatre Department. In 1931, as an ingenious gift to her friend, Bok donated $100,000 to the College for the construction of the Annie Russell Theatre. A year later, the theatre was complete, and on the night of March 29th of that year:

“[Mrs.] Russell stepped from behind the thick draperies enshrouding the stage to receive the ovation from some 500 people who had assembled to pay her tribune on this opening night. The applause which ensued was overwhelming. As her eyes slowly scanned the people before her-people who had remembered her after 15 years of absence from the stage, tears sprang to her eyes and streamed down her cheeks. Annie Russell was home.”[24]

“[Mrs.] Russell stepped from behind the thick draperies enshrouding the stage to receive the ovation from some 500 people who had assembled to pay her tribune on this opening night. The applause which ensued was overwhelming. As her eyes slowly scanned the people before her-people who had remembered her after 15 years of absence from the stage, tears sprang to her eyes and streamed down her cheeks. Annie Russell was home.”[24]

Almost immediately after the construction of the Theatre, Russell starred in the performance of Robert Browning’s play, In the Balcony, which she played opposite Rollo Peters and Mary Hone. Following this production, Russell produced and directed a performance of Romeo and Juliet. After this, Russell founded the Professional Artist’s Series, and presented the Thirteenth Chair, the vehicle in which she last performed on the professional stage. During the years that followed, she was taken seriously ill from a case of double pneumonia, which had resulted from an infected tooth. After several months of suffering, on January 16, 1936, Annie Russell quietly passed away in her sleep.

– Alia Alli

- Linda Florea, “Charles Rice, 73, led Barnett Banks,” Orlando Sentinel, C4, December 10, 2008. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- For more information on factual errors, see “Protest” by William H. Smith, in Harper’s Magazine (April 1939), 574. For a copy of the story, see “Grandmother Smith’s Plantation,” Harper’s Magazine (November, December 1938). ↵

- John Tiedtke, “My Personal Impression of the Rice Affair at Rollins College,” memorandum for the archives, (1977), 1. ↵

- Marian H. Wilcox, Letter to Hamilton Holt, 1932; Audrey L. Packham, sworn statement, 1933. ↵

- Rollins College versus The American Association of University Professors “Part II: The Grounds for Dismissal, An Analysis of the Evidence” Rollins College Bulletin 2: no. 29 (December 1933). ↵

- Witness testimony, “Grounds for Dismissal: The Case of ‘Mr. A,’” 14-15. ↵

- Mexye Ray (Great Granddaughter) in phone interview with author. July 2009. ↵

- "Jefferson County, Florida Freedmen's Contract, 1867," Florida Memory State Library & Archives of Florida, http://www.floridamemory.com/FloridaHighlights/Freedmen/ (Accessed July 8, 2009). ↵

- Mexye Ray (Great Granddaughter) in phone interview with author. July 2009. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- “A Guide to the Jessie Rittenhouse Collection.” 45 E Rollins College Archives. ↵

- Ed Hayes, “The Magical Pencil of James Gamble Rogers,” Florida Magazine, September 2, 1979. ↵

- “James Gamble Rogers II, Architect at Rollins College,” James Gamble Rogers II file, 05C, Rollins College Archives. ↵

- Susanne Hupp, “A n Architect’s Contribution: How James Gamble Rogers Defined the Charm Of a Community,” The Sentinel, G1 June 20, 1987. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Hayes, Florida Magazine, 79. ↵

- Alonzo W. Rollins (1832-1887), p. 2, Department of Archives and Special Collections, Box 10B, Olin Library, Rollins College, Winter Park, Florida. ↵

- The Winter Park Company, Alonzo W. Rollins (1832-1887), p. 3, Department of Archives and Special Collections, Box 10B, Olin Library, Rollins College, Winter Park, Florida. ↵

- Gordan B. Regan, Annie Russell and Rollins College, p 7, Department of Archives and Special Collections, Box 45E, Olin Library, Rollins College, Winter Park, Florida. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵