W

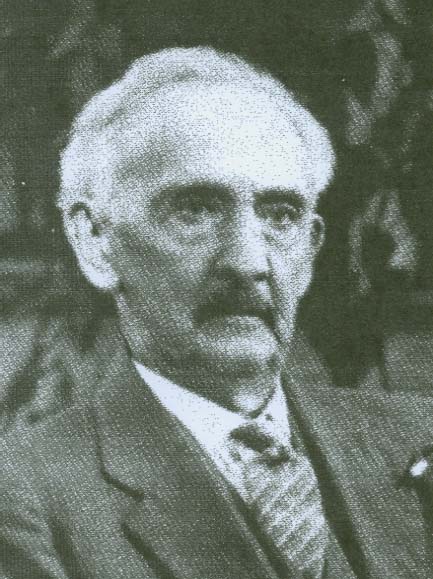

Ward, Charles Hezekiah (1848-1930)

Early Community Advocate and Leader

Charles Hezekiah Ward was born on February 24, 1848 in Montpelier, Vermont. An eighth generation Englishman, he was educated in the Montpelier public school system and spent most of his youth on the family farm. As a young man, Ward spent six years in the mercantile business in Northfield, Vermont. He dabbled in several occupations prior to becoming involved in a partnership with a general store. [1] He married Emma Ruth Chubb, a school teacher at the age of 24 on June 12, 1872. They had three sons, Charles Frederick, Harold Anson, and Raymond Ward.

Ward and his family moved to Orange Park, Florida in 1879 due to his wife’s poor health. He entered the citrus industry but was unsuccessful. He was postmaster for seven years. After resigning, he and his family moved to Central Florida. Ward arrived in Winter Park in 1886 and leased 100 acres in the village of Osceola on the eastern shore of Lake Mizell. He also rented the Spier House located at Lake Mizzell.

Ward made a second attempt to succeed in the citrus business, but the Big Freeze of 1894 proved to be detrimental. [2] Consequently, Ward cancelled his lease and bought ten acres of grove on Lake Sylvan. He built a home on his property, sought out new opportunities in business. All the while, Emma’s health improved drastically. Around the same time, Ward and his son Harold bought groves in the Winter Park area, restored them and resold them for profit. He also entered the truck-farming business and shipped fresh vegetables throughout the state of Florida. [3]

Ward was an active member of the Winter Park community. He was involved with the First Congregational Church providing flowers and grapes from his garden and serving as a Sunday school teacher. Ward was also interested in the beautification of the town. He helped establish a fresh water pumping system that helped with grove irrigation and the general water supply to the community. Ward also served on the first town council for Winter Park.

Ward’s son, Charles Frederick took over the truck farming business and was also involved in poultry and dairy operations. Later, he went into politics and was elected mayor and city manager of Winter Parks for four consecutive terms. Harold Anson Ward took over his father’s general store in Winter Park. He became part of management in the Winter Park Land Company with Charles Morse. Raymond Ward went into carpentry, was proficient in music and built airplanes during World War I.

Ward died in 1930 and his wife died in 1945. They are both buried in Palm Cemetery. He was survived by three sons, four teen grandchildren and eight great-grandchildren. Ward’s active approach in promoting positive change in the Courtesy of Winter Park Library community through projects, such as the fresh water system, and involvement in city council were paramount to the successful development of Winter Park.

– Kerem K. Rivera

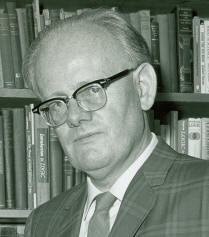

Ward, George Morgan (1859-1930)

Clergyman, Educator, 3rd President

George Morgan Ward, born to Sullivan Lawrence Ward, a practicing dentist, and Mary Frances Morgan Ward, on May 23, 1859, in Lowell, Massachusetts, descended from William Ward, who fought in King Phillip’s War. After graduating from Lowell High School, Ward studied for two years at Harvard University and later at Darthmouth College, where he received a Bachelor’s degree in 1882. Ward then engaged in the contracting business for two years, during which time he studied at the Law office of Judge George H. Stevens. Two years later, he graduated from the Law School of Boston, and later passed the bar exam. During this time, the United Society of Christian Endeavor elected Ward to replace Reverend S. Winchester Adriance as general secretary to the society. Ward maintained this position and took over the duties of editor of the Golden Rule, the society’s official magazine, until 1889, when he resigned due to his failing physical strength. Soon after, he entered a mercantile business firm at Lowell University, and later enrolled in Andover Theological Seminary and John Hopkins University simultaneously as a post-graduate student.

After obtaining several college degrees, Ward was offered pastorates in several congregational churches and presidency of more than one college. He accepted the poorest paying position at Rollins College, a young institution in Winter Park, Florida; just one year after the State had suffered its most devastating financial blow, the Big Freeze of 1895, which destroyed practically all the citrus groves throughout Florida. Through heroic efforts, Ward kept the College open during the emergency, stating to his students, “Grow old along with me, the best is yet to be, the last of life for which the first was made.” [4] Under his leadership, Rollins, hitherto a congregational institution, became inter-denominational in control, and won recognition as a pioneer in higher and religious education in Florida. During his first term, Ward super vised the construction of one new building, and witnessed the growth of faculty from fourteen to twenty-three, and an increase in the academic department from fourteen to thirty-four. Also during this period, on June 17, 1896, he married Emma Merriam daughter of Reverend Franklin Monroe Sprague of Springfield,

After obtaining several college degrees, Ward was offered pastorates in several congregational churches and presidency of more than one college. He accepted the poorest paying position at Rollins College, a young institution in Winter Park, Florida; just one year after the State had suffered its most devastating financial blow, the Big Freeze of 1895, which destroyed practically all the citrus groves throughout Florida. Through heroic efforts, Ward kept the College open during the emergency, stating to his students, “Grow old along with me, the best is yet to be, the last of life for which the first was made.” [4] Under his leadership, Rollins, hitherto a congregational institution, became inter-denominational in control, and won recognition as a pioneer in higher and religious education in Florida. During his first term, Ward super vised the construction of one new building, and witnessed the growth of faculty from fourteen to twenty-three, and an increase in the academic department from fourteen to thirty-four. Also during this period, on June 17, 1896, he married Emma Merriam daughter of Reverend Franklin Monroe Sprague of Springfield,  Massachusetts (they later had a child, who died as an infant). Just a few years later, in 1899, Ward became pastor of the Royal Poinciana Chapel in Palm Beach, Florida, preaching regularly to thousands of men and women. Ward later resigned from Rollins in 1902 to become president of Wells College in Aurora New York, where he remained for eight years. In 1916, he resumed his presidency at Rollins, and after a period of two years of Dr. Calvin H. French presidency, the College reelected Ward, where he remained without pay for four years. During that time, he headed a movement which added $500,000 to the endowment fund and paid off an indebtedness of $200,000. Ward made his final retirement from Rollins In 1922, and became the pastor of Elliot-Union Church of Lowell, Massachusetts the same year.

Massachusetts (they later had a child, who died as an infant). Just a few years later, in 1899, Ward became pastor of the Royal Poinciana Chapel in Palm Beach, Florida, preaching regularly to thousands of men and women. Ward later resigned from Rollins in 1902 to become president of Wells College in Aurora New York, where he remained for eight years. In 1916, he resumed his presidency at Rollins, and after a period of two years of Dr. Calvin H. French presidency, the College reelected Ward, where he remained without pay for four years. During that time, he headed a movement which added $500,000 to the endowment fund and paid off an indebtedness of $200,000. Ward made his final retirement from Rollins In 1922, and became the pastor of Elliot-Union Church of Lowell, Massachusetts the same year.

George Morgan Ward, clergyman, educator, president emeritus of Rollins College passed away December 28, 1930 in Palm Beach, Florida. An academic procession that included the members of the faculty and the senior class marched to Recreation Hall, where an impressive of music and tributes were conducted under the direction of President Holt. “In the death of Dr. Ward,” President Holt said, “Rollins has lost a great leader and a steadfast friend.” [5]

– Alia Alli

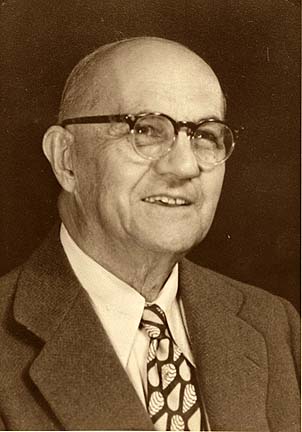

Ward, Harold Anson (1878-1954)

Alumnus and Trustee

Harold Anson Ward was born on June 12, 1878 in Burlington, Vermont to Charles Hezekiah and Emma Ward. His father was an influential member of the Winter Park community. The elder Ward helped establish a fresh water pumping system and was a member of the town council. Harold’s family moved to Orange Park, Florida in 1879. A failed citrus grove led the family to relocate to Winter Park in 1886. The family home was located on Lake Sylvan.

Harold attended Winter Park public schools. He also attended the Rollins College Academy and graduated in 1895. Upon graduation, Harold was involved with the Winter Park Pioneer Store for ten years. [6] He also married Annie M. Griffin in Asheville, North Carolina on October 22, 1902. He had eight children, Harold A. Jr., Gertrude, Ruth, Ernest, Earl, Walter, Florence and Margaret.

Throughout his time in Winter Park, Harold Ward was involved in the Winter Park Land Company along with Charles Morse. In March of 1904 he became the manager for Charles H. Morse’s property. He continued after Morse’s death in 1921. Ward played an important role in persuading Morse to purchase the Knowles estate. The latter was made up of about some thousand lots in the city and the surrounding area. Ward also served as tax collector, tax assessor, city clerk, alderman and mayor of Winter Park.

Harold was heavily involved in the community. He was a member of the Congregational Church, Business Men’s Club, Aloma Country Club and Chamber of Commerce as well as president of the Winter Park Fruit Company. He established the Winter Park Refrigeration Company with H. Earl Cole and helped build the first pre-cooling plant for oranges in Winter Park. Ward and Cole sold the plant and incorporated as the Lake Charm Fruit Company. Ward was also vice president of the Bank of Winter Park, a member of the Winter Park Public School Board and a trustee for the Hungerford Normal and Industrial School in Eatonville, Florida. Ward founded the Winter Park Insurance Agency and was a l so president of the Goldenrod Corporation. The Goldenrod Corporation held a partnership with the Winter Park insurance Agency.

Harold became a Rollins College trustee in 1923. Links between the Ward family would continue with children and his thirteen grandchildren. On May 14, 1929 he married Charlotte McKee from Aspen, Colorado. Harold Anson Ward died on June 13, 1954.

– Kerem K. Rivera

Warren, Frances Knowles (1872-1953)

Continuing a Legacy of Benefactions

Frances Knowles Warren was born in 1872 in Worchester Massachusetts. Her father, Francis Bangs Knowles was the founder of the Knowles Company, a textile machinery manufacturer located in Worchester, Massachusetts. Later on, he and an acquaintance formed the Knowles & Crompton Company. The company became one of the largest manufacturers of textile machinery in the world. [7] Frances’ mother, Hester A. (Greene) Knowles was the second wife of Francis Bangs Knowles and bore him three children including Frances.

Warren was educated in Worcester public schools and at the Dana Hall School in Wellesly. She married George C. Warren, the head of a coal company in Boston. Following the nuptials the Warrens moved to Boston where they lived comfortably on the well-known Beacon Street. Frances and George had no children. Perhaps because of this, she was heavily involved in the community as a member of the Trinity Church of Boston, president and director of the Boston YWCA and work with the Free Hospital for Women, Student’s House, the Industrial School for Crippled Children, Trinity Home for the Aged and the Boston branch of the National Cathedral Association. She was also director of Knowles & Crompton. Her brother, Lucius James Knowles was president of the company from 1916 until his death in 1920. After George died, Warren moved to the Ritz-Carlton Hotel in Boston. She spent her summers in Manchester, Massachusetts and her winters in Winter Park, Florida.

Warren was acquainted with Rollins College since childhood. Her father was a founder, benefactor, and trustee. She carried on her family’s involvement with Rollins. Warren donated a surfeit of money to the school. She left behind a trust fund valued at $1,516,314. She provided the funds for the construction of the Knowles Memorial Chapel, dedicated to her father, the Warren Administrative Building and the Student Center. Knowles Memorial Chapel took almost one year to build and cost $162,805. Mrs. Warren’s financial assistance made the installation of air conditioning to the Warren administration building possible. She was interested in increasing the beauty and usefulness of buildings throughout the campus and in helping students, both in the North and South, attain higher education. [8]

On March 1, 1935 Warren was awarded a degree of Doctor of Humanities by President Hamilton Holt. She was also the recipient of the Algernon Sydney Sullivan Medallion in February 1943 and made an honorary member of the Order of the Libra, an honorary service society at Rollins.

Frances Knowles Warren passed away on October 25, 1953 in Boston, Massachusetts. She and her father were well known for being generous donors and friends to the students, faculty, and members of the Rollins and Winter Park community.

– Kerem K. Rivera

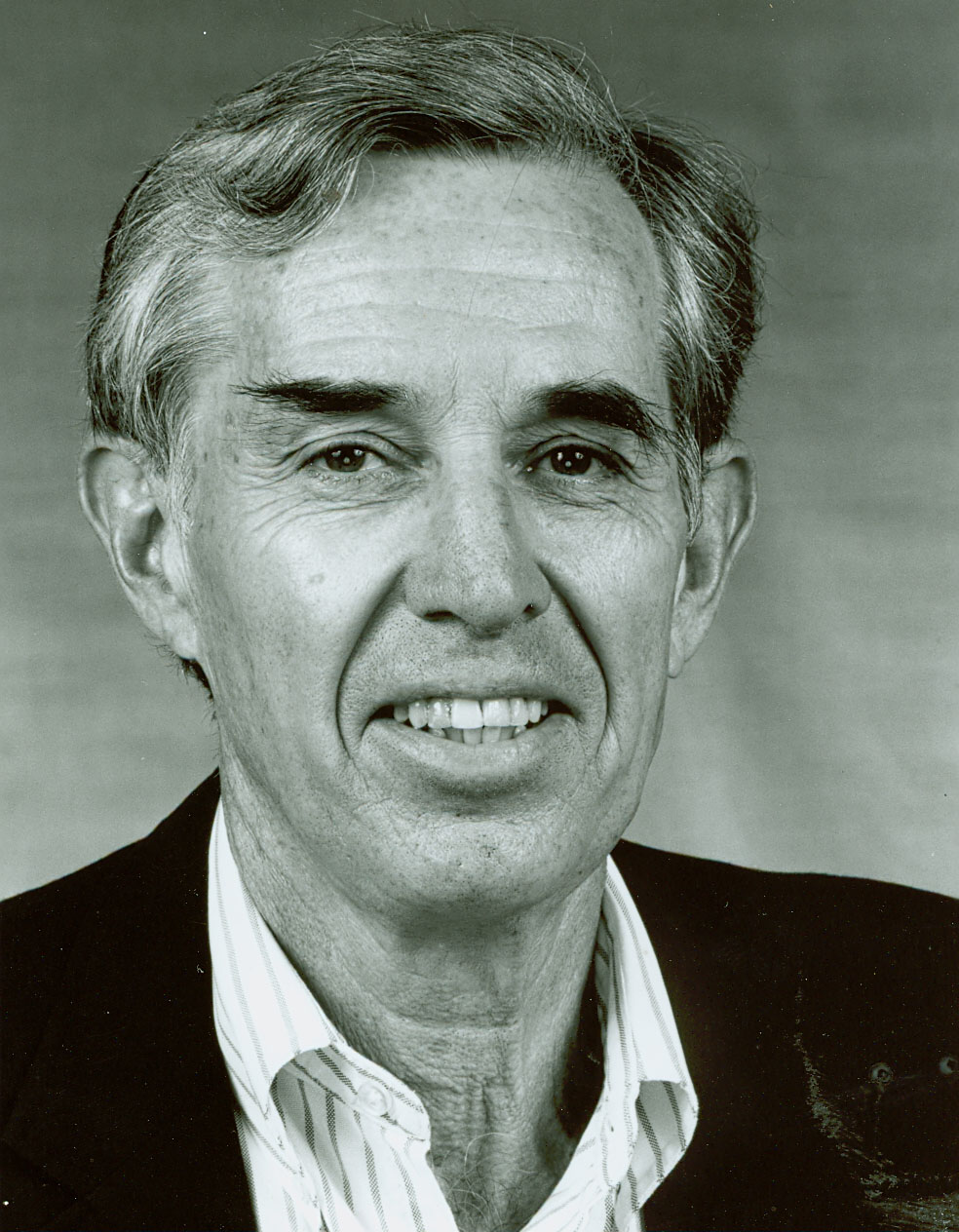

Wavell, Bruce B. (1916-1983)

Philosopher and Logician

Article as it originally appeared in The Alumni Record, Vol. 60:3 (Summer 1983), 41.

“…Every inch a professor”

The following words were spoken by Dr. Daniel R. DeNicola at a memorial service for Bruce Wavell at the Knowles Memorial Chapel on April 22, 1983.

When the brilliant philosopher, Ludwig Wittgenstein, was teaching at Cambridge University in the early 1930’s, he was accosted by a tall, serious undergraduate studying mathematics and physics who had a cheeky request: he wanted to sit in on Wittgenstein’s graduate lectures. After a lengthy conversation, Wittgenstein agreed, and Bruce Wavell became the only undergraduate ever permitted to witness the genius at work, thinking through philosophical problems before his crowded classroom with a frightening and exhausting intensity. This experience made an indelible impression on Bruce. It affected his sense of what it is to do philosophy and what it is to teach. Unlike Wittgenstein, who continually feared for his own sanity, Bruce’s brilliance was combined with a profound and humane sanity.

In the 1950s, Bruce earned his PhD. in Mathematical Logic at the University of London under Sir Karl Popper. The intervening years were spent in diverse and interesting roles- all of which seemed to add something important to Bruce’s understanding of the world. He was a grammar school mathematics master (he loved geometry), a senior lecturer in telecommunications for the Army Signal Corps, an engineer in charge of technical publications, a sojourner in a monastery. He married Joan Plater and became a devoted father. He came to believe that a loving and sustaining marriage and parenthood call upon virtues and offer joys like no other institution. He came to Rollins in 1959 to teach mathematics and logic, choosing this institution over others because, as he once told me, “I thought they wanted a good teacher at Rollins, and having grown up in Malaya, I innocently imagined the Florida climate to be somewhat similar. “Nearly all of Bruce’s philosophical work was done at Rollins. For 23 years full of students and colleagues here he became, as one friend has said, “the only one of us who was every inch a professor.”

Bruce became concerned that the formal logic he was teaching did not apply to practical contexts- did not help his students decide what to do or what to believe. This problem arose, he concluded, because formal logic was based on mathematical models, not on human communication, natural language. He came to believe that our ordinary language contains a hidden logic waiting to be revealed by careful study. This he formalized in his first book, Natural Logic– a symbolic logic based on ordinary English.

This latent logic, this logos, this Reason at work in our ordinary discourse is marvelously complex and subtle, bespeaking the slow but impressive evolution of culture. Science and art and the law-even Robert’s Rules of Order, he believed-all represented sophisticated refinements of the “common sense” reason present in everyday conversation. As his vigorous, polymathic mind ranged over these different “universes of discourse,” as he called them, he found the pattern repeated: each was imbued with and organized by the force of human reason. None of us is fully aware of this, of course; that is the task of enlightenment. The ancient injunction to “know thyself ” is echoing here. Bruce would say that self-understanding means understanding the order, the reason implicit in our culture and in its institutions, to see how our concepts work and beyond them to the Logos which gives them form and function.

A poet-in-residence once sent me this two-line poem:

On Bruce Wavell’s Rising to Speak at a Faculty Meeting:

He Stands

To Reason.

Bruce was not a rationalist in the traditional sense. He did not believe this to be a rational world. “A demented world,” “a crazed world,” he called it. But he believed this is a world in which we can find the guiding force of Reason, if only we awake to it. He rejected the dualism of mind and body, of reason and passion. He made the understanding and improvement of practice the highest of his theories. Certainly Bruce believed that proper procedures of deliberation, rational decision procedures, were required by reason, and he devoted great energy to systems for assigning due weight to relevant factors. But remember that he said the enlightened person, like the Buddha,

“… is able to perform this feat

Each moment of his life,

Because he is at one,

In Harmony,

With the Logos. “

In how many memorable classes and conversations with Bruce have we heard these themes? As he sat forward in his chair, fiddling with his pipe, eye twinkling and face glowing as he warmed to his point, passionately defending reason, he seemed the Logos incarnate. How he surprised us! The mathematician who quoted lyric poetry; the logician and engineer who pursued Buddhism as a way to get beyond the useful constraints of our concepts; the dignified scholar with the bemused countenance and the hearty laugh in the stately and colorful academic garb; the department head o f strong opinions who recruited faculty of different beliefs, with whom he could argue. That we should be surprised shows our own limitations; for Bruce, all these, his teaching, his research, his service to the College, his public and personal life, were done as a single graceful act.

Some years ago I quoted from Michael Oakeshott a passage which Bruce loved:

“As civilized human beings, we are the inheritors, of a conversation, begun in the primeval forests and extended and made more articulate in the course of centuries. It is a conversation that goes on both in public and within each of ourselves . . . . . . Education, properly speaking, is an initiation into the skill and partnership of this conversation in which we learn to recognize the voices, to distinguish the proper occasions of utterance, and in which we acquire the intellectual and moral habits appropriate to conversation. And it is this conversation which, in the end, gives place and character to every human activity and utterance.”

For us, his family, friends, students and colleagues, Bruce not only contributed to this conversation, he helped us understand it. And already we miss his voice.

– Daniel R. DeNicola

“We have lost one of our most distinguished colleagues. His influence on Rollins students and faculty as teacher, scholar and philosopher is incalculable. Never have we known such a passionate faith in human reason.”

So spoke Rollins Dean of the Faculty Daniel R. DeNicola of his former teaching colleague, Dr. Bruce Wavell, who died unexpectedly on April 15, 1983. Bruce Brooke Wavell, who held the position of William R. Kenan, Jr. Professor- Emeritus of Philosophy, joined the Rollins faculty in 1959 as Assistant Professor of Mathematics and retired from full-time teaching following the 1981-82 academic year. A native of Hove, England, he attended Christ’s College, Cambridge and received the B.S. and Ph.D. degrees from London University. In 1961, Dr. Wavell attracted a grant to Rollins College from the National Science Foundation for a summer mathematics program for gifted high school students. He founded the Honors Program at Rollins and served as its director for many years. In 1962, he left the mathematics department and assumed teaching responsibilities in the Department of Philosophy & Religion, where he taught “‘Logic,” “Philosophy of Law,” “Philosophy of Science” and “Values Theory.” Wavell was a past president of the Florida Philosophical Association and a member of the American Philosophical Association and the Semiotic Society of America. He wrote four books: Language and Reason, The Lining Logos: Philosophico-Religious Essay, Natural Logic and Teaching Values in the Liberal Arts, the latter manuscript currently pending publication. He also wrote numerous articles, including his most recent contribution, “Scientific and Religious Universes of Discourse,” which appeared in the December 1982 issue of ZYGON, The Journal of Science and Religion, published by Rollins College. His latest paper, “Wittgenstein’s Doctrine of Use,” will be published posthumously in Synthese by Reidel Publishing Co., Dordrecht, Holland. Dr. Wa vell is survived by his wife, Joan Plater Wavell, Administrator of the Cornell Fine Arts Center at Rollins three children, Richard, Barbara (a 1976 graduate of Rollins) and Alice Daphne Wavell; and a brother, Stewart who lives in England. The family has requested that remembrances be offered through the Book-A-Year Memorial Program at Rollins.

Wattles, Willard A. (1888-1950)

Original Golden Personality

On June 8, 1888, farmer and lumber dealer, Harvey Austin Wattles and his wife, Jennie Fay Wattles gave birth to Willard Austin Wattles in Baynesville, Kansas. After completing his undergraduate studies at the University of Kansas in 1909, Willard Wattles began his teaching career as an English instructor at a high school in Leavenworth, Texas. Wattles returned to Kansas University for another two years, completing a fellowship and Master’s degree by 1911. Wattles spent the next nine years in academia, instructing students in English at Leavenworth High School, the University of Massachusetts, and the University of Kansas. After graduating from Princeton in 1921, Wattles moved to Connecticut and then Oregon, where he continued to teach and pursue his love for poetry.

Soon after, Wattles became widely recognized, not only for his teaching background, but also for his authorship of several books, including Lanterns: the Funston Double-Track and Other Poems (1918), Compass for Sailors (1928), and for the publication of his poems in The Independent. Hamilton Holt, editor of The Independent and president of Rollins College, was so impressed by his work that he requested Wattles’ presence at Rollins. In 1927, Wattles joined the faculty, bringing the “qualities of heart and mind that made him greatly beloved by the students.” [9] Wattles immediately became involved with the College, working as faculty advisor for The Sandspur, The Tomokan, and The Flamingo. Wattles made outside contributions as well, including his 1929 summer involvement with Breadloaf School of English. Through such services, Wattles revealed his “sound understanding of student problems and his judicial fairness.” [10] By 1938, Rollins named Wattles chairman of the division of English, and later, professor of American Literature. By 1945, Rollins granted Wattles with a Doctor of Literature degree. Wattles remained at the College for another five years, making a final self-publication (Six Guys and a Girl) of poems written by seven students in his contemporary poetry class.

On September 25, 1950, Willard Wattles died of a heart attack, leaving behind his membership to the American Editorial Association, the Poetry Society of America, and to the Tenth Division of the U.S. Army. In honor of his involvement, the Omnipotent Order of Osceola presented Mrs. Wattles with a plaque, inscribed, “to our teacher and friend, Willard Austin Wattles…we walk together when we are apart, our eyes have met and what we saw, no man shall know, nor forget.” [11]

-Alia Alli

Wesley, Susan (c. 1887 – ?)

Maid of Cloverleaf and Decoration of Honor Recipient

Born in Thomasville, Georgia, Susan Wesley (ca. 1887-?) traveled further South to Winter Park, Florida where she lived the remainder of her life.

There she became active in the community, working in the Baptist Church and other various organizations. In 1924 Wesley joined Rollins College, where she became a housemaid in Cloverleaf Cottage. Built in 1891, the Cottage was then described by the Winter Park Advocate as one of the largest and prettiest buildings in town. The 56-room building included a cylindrical tower and three wings, each three-story high and in the shape of a cloverleaf. [12] Over the next twenty-five years, Wesley served nearly fifteen-hundred freshman girls at the College, treating them “through sickness and in health, in joy and in sorrow.” [13]

Wesley displayed further faithfulness towards her post during the 1944 hurricane, where she remained at the College despite the dangerous winds and heavy rain. According to an interview done with Ms. Wesley, many urged her to return home, but she refused, claiming she would rather be in Cloverleaf. [14] The morning of the hurricane, a strong gust of wind forced a store window in, causing a piece of glass to fly up and hit her. An even stronger gust lifted her up and carried her back down the street. “Nothing really disturbed her though until she reached the campus where the girls were yelling ‘hurry up Suzy, run.” [15]

During the 1948 commencement ceremony, President Hamilton Holt remarked: “Susie Wesley, for your many years of faithful service to Rollins, during which you and I have both worked for the college that we love; for your help to many hundreds of Rollins freshman girls; for your influence in Winter Park through church and club; for your generous service far beyond the call of duty; for your life as a Christian woman and a loving follower of our Lord Jesus Christ, Rollins College is honored in conferring on you the Decoration of Honor and admits you to all its rights and privileges.” [16]

– Alia Alli

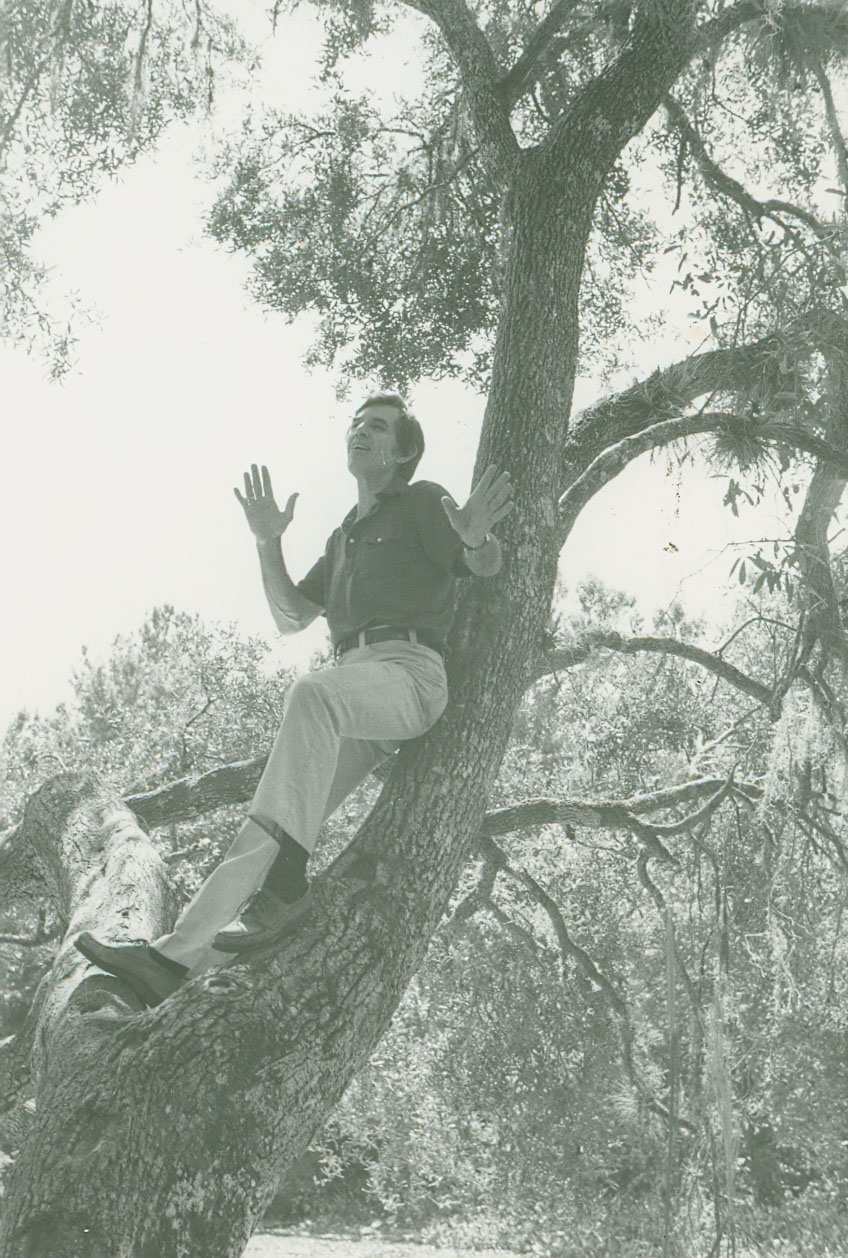

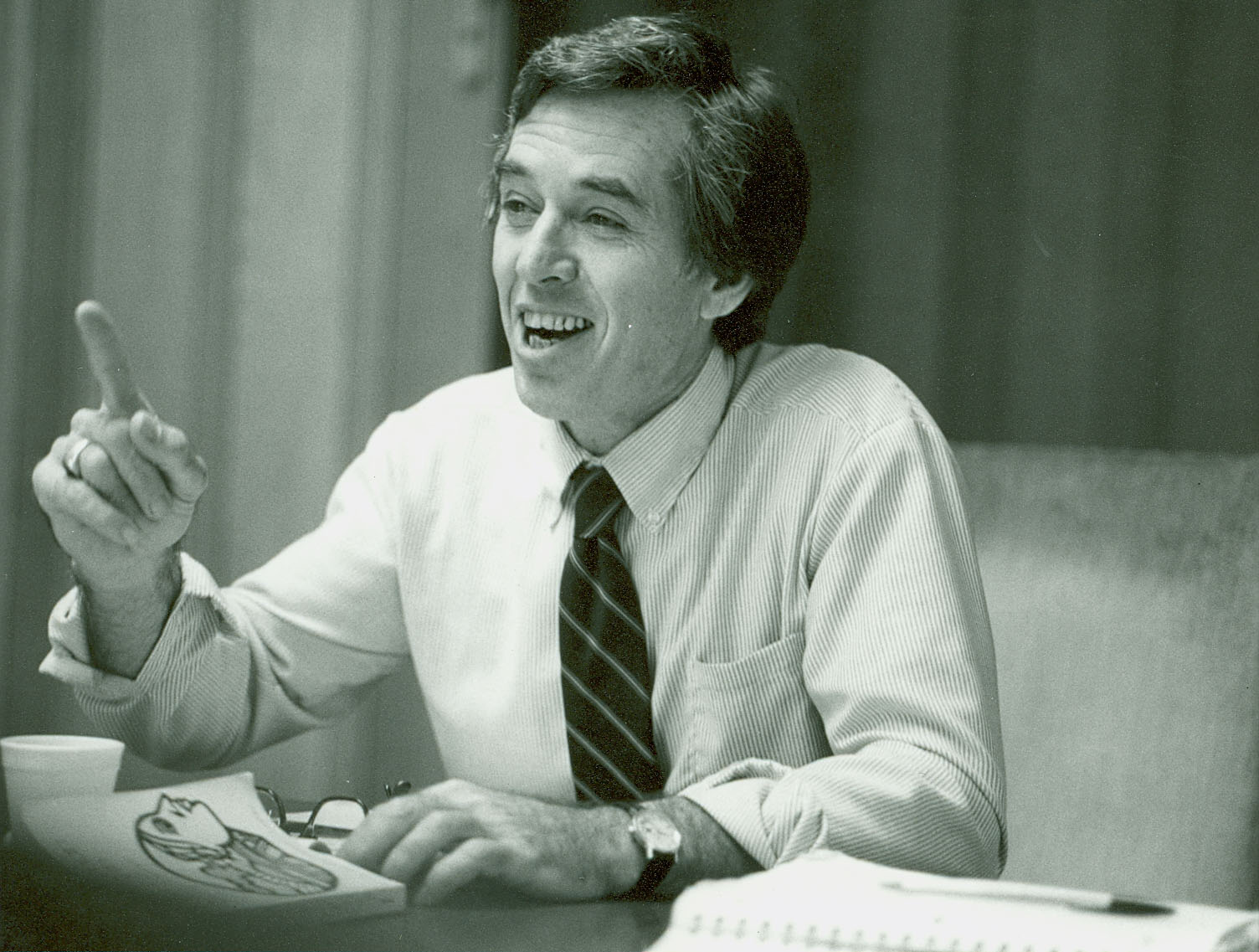

Wettstein, Adelbert Arnold (1928-2008)

Dean of Chapel

Article as it originally appeared in the Rollins Magazine, (Spring 2006), 16-20.

WE SPEAK OFTEN OF “COMMUNITY” at Rollins College- a place where students, faculty, and staff know each other; a place where the ideal of a coherent community has a powerful impact on campus life. But community doesn’t just happen; it must be initiated and sustained each day by individuals through practical activities.

For more than 30 years, a prime nurturer of Rollins’ community spirit was A. Arnold Wettstein ’06H, professor emeritus of religion and dean emeritus of the Knowles Memorial Chapel. “The Dean” departed this world on May 30, 2008, after 80 vibrant years, yet his wisdom, compassion, and humor remain a permanent and humane influence in the hearts of generations of Rollins students and colleagues.

At a College memorial service for Dean Wettstein in September, hundreds of his admirers filled the Chapel where he presided for more than two decades. “In listening to our alumni, I am struck by the wonderful stories about Arnold. Everyone had a story to tell. And he was the best storyteller I ever knew,” said former Rollins president Thaddeus Seymour ’82HAL, ’90H. Thad finished his own series of stories about Dean Wettstein by quoting the inscription embedded in the wood of the Chapel pulpit, dedicated to Rollins’ second president, George Morgan Ward, but equally applicable to Wettstein: “A man greatly loved, of rare personality and ability, consecrated to the service of God, who gave himself to the needs of others with unselfish devotion.”

At a College memorial service for Dean Wettstein in September, hundreds of his admirers filled the Chapel where he presided for more than two decades. “In listening to our alumni, I am struck by the wonderful stories about Arnold. Everyone had a story to tell. And he was the best storyteller I ever knew,” said former Rollins president Thaddeus Seymour ’82HAL, ’90H. Thad finished his own series of stories about Dean Wettstein by quoting the inscription embedded in the wood of the Chapel pulpit, dedicated to Rollins’ second president, George Morgan Ward, but equally applicable to Wettstein: “A man greatly loved, of rare personality and ability, consecrated to the service of God, who gave himself to the needs of others with unselfish devotion.”

Although many knew Wettstein, his personality was so rich and varied that most knew only parts of him. Probably few outside the family knew his first name was Adelbert, after his German-American father. His college buddies called him “Biff,” a name most would have trouble associating with such a brilliant and distinguished man. As an undergraduate at Princeton University, he studied medicine until deciding that society’s most critical ills were “spiritual rather than physical.”

Few knew that he once served as a chaplain in the Navy, although many shared his love of sailing. No one would be surprised that he was awarded Rollins’ coveted Arthur Vining Davis Fellowship for outstanding teaching, but not many knew he was the first to receive it, in 1971.

Few knew that he once served as a chaplain in the Navy, although many shared his love of sailing. No one would be surprised that he was awarded Rollins’ coveted Arthur Vining Davis Fellowship for outstanding teaching, but not many knew he was the first to receive it, in 1971.

Wettstein’s biography is impressive. After earning an AB from Princeton in 1948, he began his education in the ministry at Princeton Theological Seminary and went on to receive a bachelor of divinity degree f rom Union Theological Seminary, studying under two of the greatest Protestant theologians of the 20th century, Paul Tillich and Reinhold Niebuhr. On June 19, 1951, he was ordained into the ministry at The Reformed Church of Hoboken, New Jersey, where his father served as minister.

Soon after, he began graduate studies at Columbia University in New York, but left to serve as an interim pastor at the First Presbyterian Church in Cooperstown, New York, where he met his future wife, Marguerite. He then entered military service, serving as a Navy chaplain from 1950 to 1954. He returned to civilian ministry, eventually becoming ordained in the United Church of Christ.

Wettstein resumed his graduate studies at McGill University, receiving his Ph.D. in philosophy and religion in 1968. He Joined the Rollins community as assistant professor of religion and assistant dean of the Chapel. In 1973, he was appointed dean, a position he held until 1992. Upon his retirement as a professor in 1998, he continued to teach at Rollins and minister to others’ needs. In 2006, the College awarded him an honorary doctorate for his long and faithful service.

Wettstein was an influential religious leader. He served as president of the National Association of College and University Chaplains, was an active member of the North American Paul Tillich Society of Theologians and the First Congregational Church of Winter Park, and served as chaplain of the Ethics Committee of the Mayflower Retirement Center in Winter Park, where he spent his final days. He often attended services at the Congregational Church and sometimes filled in as minister. As his good friend and former Congregational Church minister Rev. James Armstrong said at Wettstein’s memorial service, “When he attended, was always aware of his presence. I chose my words carefully, and he listened thoughtfully. I wanted to pass that intellectual litmus test.” High praise indeed from someone known for his powerful sermons and who once served as head of the National Council of Churches.

But the true measure of the man was the love, affection, and respect Wettstein inspired in others, from his fellow faculty to the many students who sought to emulate him. Everyone remembers that warm, baritone voice of his, as perfectly suited to the utterance of great thoughts as to the punch lines of his jokes. For many, he will be most remembered for the inspiring sermons that lifted the spirits and challenged the souls of the church communities he served. Brian Crowley ’90, who first met the dean as a student in his religion class, said, “His were the best and most meaningful sermons I’d ever witnessed. It has been almost 20 years, and no one has come close to weaving substance and relevance into a homily as he could.”

Wettstein taught courses on world religions, contemporary religious thought, and alternative religions in America. “I took several classes with Arnold, including a course on cults and alternative religions in which we formed our own cult at the end of the semester- The Wettsteinians- much to his surprise!” said Ginny Cawley-Berland ’81. “I will always remember his infectious excitement about everything he taught and everything he did on campus, and his smile-beatific with a dash of mischief. He opened my eyes and broadened my very narrow view of the world. And he helped me to see that religion and faith are not the same thing, and do not always go hand-in-hand.”

Wettstein was ahead of his time in building bridges to representatives of other denominations. Steeped in many world religions, he emphasized their common features and best characteristics. He invited religious leaders of many faiths to campus for worship and “interfaith dialogue.” During the apartheid era, he went to South Africa as a guest of Archbishop Desmond Tutu to lecture and give sermons, and Bishop Tutu sent his assistant pastor to speak at Rollins. Wettstein even brought a Zen roshi (master) to campus and sponsored Zen meditation retreats, encouraging others to learn how to apply meditation to their own religious beliefs. “He made me feel uncomfortable at times because of his interest in and knowledge about far Eastern religions,” said Beth Hobbs Lannen ’79. “At that time, I suppose thought it was ‘sinful’ for a Christian to be delving into other religions. Sounds silly to me now.”

Wettstein did not just preach religious ideals; he lived and expressed them in his deeds. His spirit of tolerance, compassion, and respect for diverse views was a guiding force at Rollins. As his former faculty colleague Hoyt Edge said, “He was always a voice of reason and compromise in faculty meetings. Arnold was the conscience of the College.”

The Dean had a gift for motivating his students to learn and exciting them about service to society. Although he always placed students and other colleagues in the forefront, he was the driving force behind the finals week pancake breakfasts, the World Hunger Committee, and the concerts on behalf of Oxfam to alleviate hunger in poverty-stricken countries. For years, Rollins’ contributions to Oxfam outstripped those of much larger universities. He got students involved in Daily Bread, which feeds Orlando’s homeless. For Rick Taylor ’81 , he embodied a characteristic aphorism of St. Francis of Assisi: “Proclaim the gospel boldly, and if necessary, use words.”

Wettstein initiated service-learning courses in Jamaica, Guatemala, Uganda, and Ghana, and helped to initiate projects for Habitat for Humanity International- activities which have become a centerpiece of Rollins education today. He once told an interviewer, “Well, what inspired me was… I felt I couldn’t really teach ethics in an affluent society very well without having a confrontation with the problems as they really are. You just can’t come to any significant ethical conclusions when you’re sitting in your chaise lounge or driving your convertible to the beach.”

Though his dignity and wisdom made him a figure of reverence, Wettstein was also “cool” in an endearing way to young people. He accepted students’ non-academic aspirations and interests and nurtured them intuitively.” As intelligent as Arnold Wettstein was, I will always remember him for his ability to suspend the social mores of what a dean of the Chapel ‘should’ be like and ‘ought’ to do, and make decisions that were instead inspired by love,” said Woody Nash ’90. “He knew that as architecturally impressive and sacred as the Knowles Memorial Chapel is, it was spiritually lifeless unless it attracted and served the Rollins community.” Perhaps one of the achievements of which Wettstein was most proud was marrying more than 500 Rollins alumni in the Chapel.

Wettstein had a mischievous sense of humor that endeared him to many; he loved the theater, pranks, and witticisms, and took pleasure in life’s everyday absurdities. At bottom, however, he was a deeply serious man who spent his life pondering life’s greatest mysteries, understanding and finding common ideals among the world’s various religions, and working to help his students, his community, and the world at large to find peace and harmony. He took pleasure in people’s differences, yet worked to help them see their common humanity. He wanted people to take themselves less seriously, but find serious purpose in their lives.

“Arnold loved life,” said John Langfitt ’81MS, who served as Wettstein’s assistant dean and coordinator of the Sullivan House campus ministry. “He enjoyed adventure as well as theological and intellectual discussion. He was a peacemaker and on the cutting edge of the important ethical issues of the day. He broadened Christianity into a world perspective. He laughed and loved and worshiped and played, but he took us to a higher level of intellectuality and spirituality that made us more excited about God and life.”

Not long after Wettstein died, his son Fritz ’83 had an experience that embodies the influence the dean had on so many people. “It’s hard listening to the readings at church and not thinking about how Dad would interpret them,” Fritz said. “I was at a service where the minister read Matthew 10:39. ‘Jesus said: Those who find their life will lose it, and those who lose their life for my sake will find it.’ He explained that these words were recalled and written down at a time when an early Christian’s risk of death and possibilities at martyrdom were very real. He went on to give a good lesson on bearing the cross for Christ. Still, I sat and wondered, ‘What would my Dad say?”‘

For many Rollins alumni pondering life’s mysteries in adulthood, we wonder, what would Dean Wettstein say about that? As he always wanted us to, we must draw our own conclusions, but our spirits are buoyed by the memory of his confidence in us.

– Bobby Davis

- “Winter Park History and Archives Collection: The Ward Family Collection,” Winter Park Library, http://www.wppl.org/wphistory/WinterParkBiographies/Ward.htm. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- George Morgan Ward, Department of Archives and Special Collections, Box 20D-E: 2 of 4, Olin Library, Rollins College, Winter Park, Florida. ↵

- Hamilton Holt, “President Holt Pays Tribune to Noted Educator,” Department of Archives and Special Collections, Box 20D-E: 2 of 4, Olin Library, Rollins College, Winter Park, Florida. ↵

- William Fremont Blackman, History of Orange County Florida. (DeLand, Florida: The E. O. Painter Printing Co., 1927), 59. ↵

- “Frances K. Warren Trust: Background Information,” Frances Knowles Warren file, 10B, Rollins College Archives. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- “Who’s Who at Rollins College,” Winter Park Herald, December 21, 1934. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- “Plaque for Professor,” Rollins College Archives, Box 45E, Winter Park Florida. ↵

- Zhang, Wenxian, Eneid Bano, and Charles Stevens, Rollins Architecture: A Pictorial Profile of Current and Historical Buildings, Winter Park: Rollins College, 2009. ↵

- Dean Cleveland, “Decoration of Honor,” June 2, 1948. Department of Archives and Special Collections, Box 43C, Olin Library, Rollins College, Winter Park, Florida. ↵

- “Let’s Sing a Song About Suzy,” Rollins Sandspur, November 1, 1944. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Hamilton Holt, “Decoration of Honor,” June 2, 1948. Department of Archives and Special Collections, Box 43C, Olin Library, Rollins College, Winter Park, Florida. ↵